Agnes Scott College and the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War incited a variety of responses in the U.S and around the world. Counterculture movements were emerging in the West, and the youth, in particular, were hungry for change. Perceiving that politics were out of step with popular opinion, many students became alienated from institutional power structures. The Vietnam War indelibly shaped Agnes Scott College, starting a wave of student activism: students sought out provocative speakers, flirted with radical ideas and advocated for institutional change. Agnes Scott administrators and alumnae were caught between patriotic loyalty and the daily challenges faced on the home front. The ideological divide between the two groups was a generational rift that could not be breached.

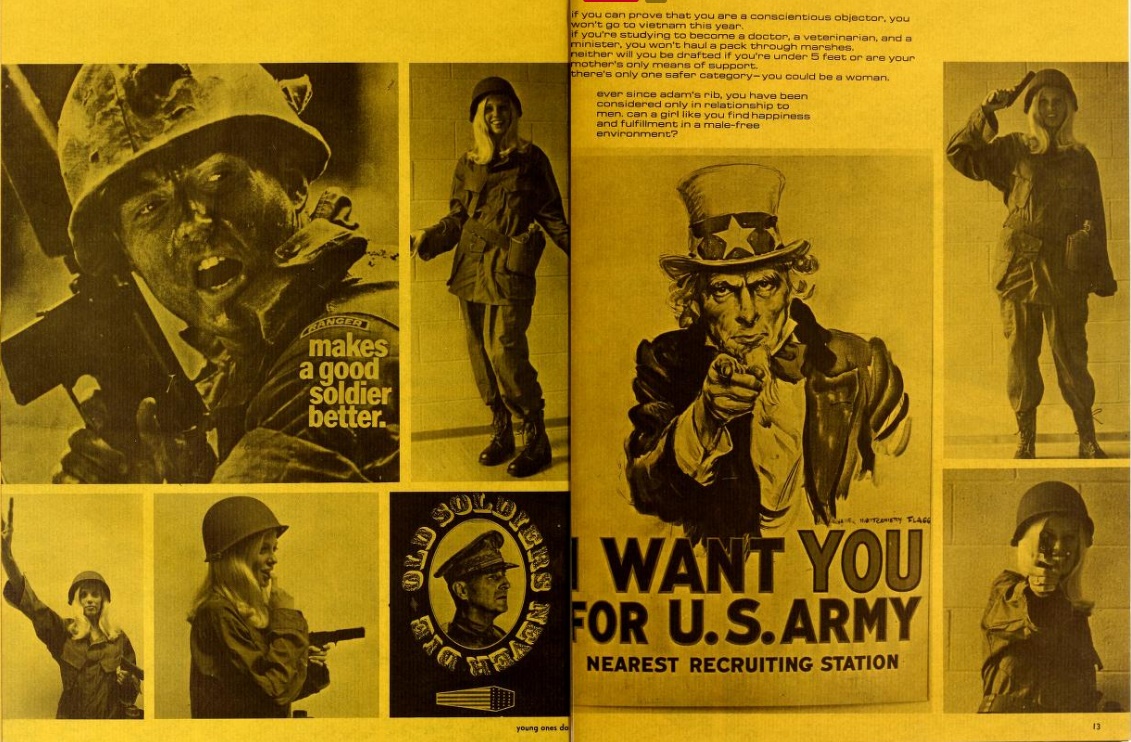

A two-page spread from the Agnes Scott 1969 Yearbook which discusses and mocks draft avoidance. The safest way not to be drafted, the page claims, is to be a woman (Image courtesy of Agnes Scott College, McCain Library Archives)

Vietnam was lost in the living rooms of America – not on the battlefields of Vietnam – Marshall McLuhan

The Vietnam War began in 1955, but few American’s took note of it before the mid-1960’s due to several reasons. The new-fangled television culture brought the vivid news footage into comfortable living rooms across America. The escalation of American interventionism in Vietnam, despite the government’s assertion to the contrary, created a gap between official government policy and reality, causing the public to perceive President Johnson as duplicitous. Activism, particularly among the youth, became mainstream due to shifting public perception. Students became politically involved and mobilized, seeking alternative methods to make their voices heard. In 1968, Viet Cong forces launched a surprise attack on thirteen cities in South Vietnam. Though the United States and South Vietnamese successfully defended against The Tet Offensive, making it a military success, it further soured the public approval of the war. The request for additional troops along with the high death toll made the so-called ‘victory’ seem hollow.

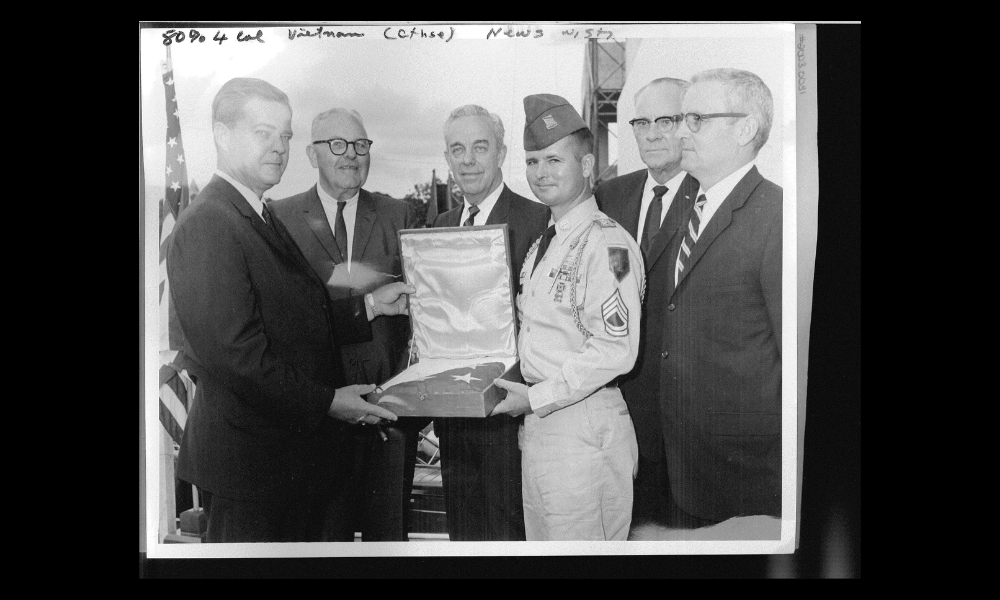

Though the majority of Agnes Scott students supported the Vietnam War during its early years, by the mid-1960’s, students echoed popular feelings and began to oppose the war. In 1966, Junior Jaunt Charity Drive, an annual school event, raised nearly eight hundred dollars to support impoverished refugees in Vietnam. One year later in 1967, General Maxwell Taylor, the former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, was invited to lecture about the Vietnam War, demonstrating Agnes Scott ’s active engagement with wartime issues.

Students across the nation felt that higher education was increasingly irrelevant and sought to affect change where they were able, primarily on college campuses. Student activism took on a variety of forms, from inviting guest speakers, such as General Taylor, to re-evaluating the quality of an Agnes Scott education. In 1967, the Representative Council sought to “measure its curriculum… with the perspective of the world beyond the railroad tracks.” Students at the college believed that the curriculum reflected a narrow, detached worldview.

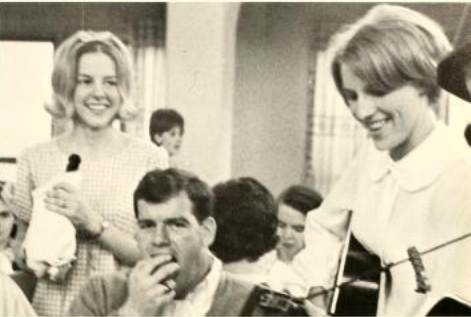

- Agnes Scott Juniors participate in the the Junior Jaunt in 1967 (Image courtesy of Agnes Scott)

- Students pour wine and perform to raise money for the Junior Jaunt (Image Courtesy of Agnes Scott).

- The 1966-1967 Representative Council of Agnes Scott College (Image courtesy of Agnes Scott)

- General Maxwell Taylor is pictured above with Agnes Scott Students (Image Courtesy of Agnes Scott)

As a result of this, seminars on Vietnam and China were introduced into the curriculum. This marked a sea-change; the school developed academic programs that stressed student participation and examined current events. These changes dramatically increased student involvement, academically and socially. The Profile, Agnes Scott’s student newspaper, chronicled the wide variety of anti-war activities that took place on the Agnes Scott campus: from meetings with Congressional Representatives, reporting on protests across country, particularly at the University of Berkeley, signing amicus curiae briefs, to planning protests and debating the ideas of national student movement organizations, such as the National Student Organization.

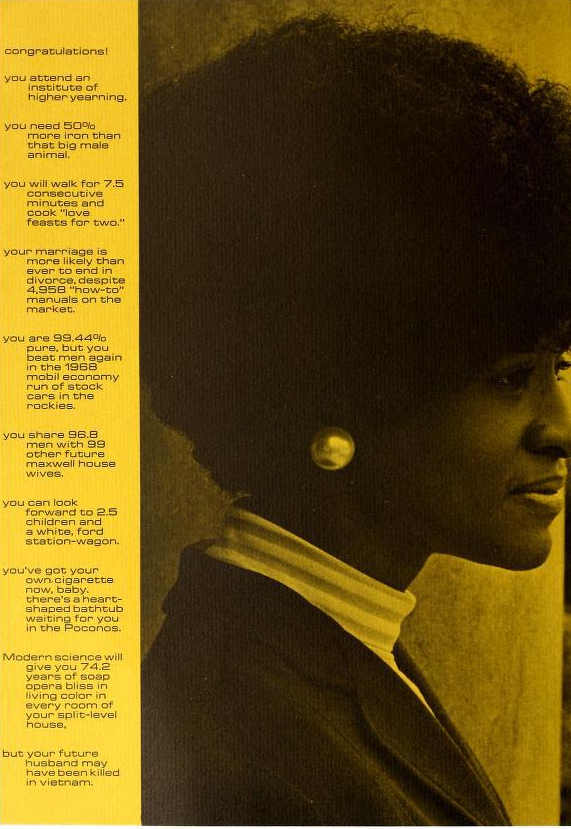

A two page spread from the 1969 Silhouette yearbook. The introduction sarcastically talks about life ahead for the students, notably that their future husbands may be dead from service in Vietnam (Image courtesy of Agnes Scott College, McCain Archives).

As the number of deaths began to rise, cynicism set in among Agnes Scott students. The 1969 publication of the Silhouette, the student yearbook, captures this tone well. The opening introduction stated, “Congratulations! Modern science will give you 74.2 years of soap opera domestic bliss… but your future husband [has] been killed in Vietnam.” The student yearbook editors not only mocked the traditions of prior generations (love feasts, sharing husbands with other Maxwell Coffee wives, honeymooning in the Poconos, etc.) but also illustrated how life had dramatically changed from the Baby Boomer to the Cold War Generations. As one page sarcastically noted, “ever since Adam’s rib, you have been considered only in relationship to man. Can a girl like you find happiness and fulfilment in a male-free world?”

Students were not content with the previous status quo. A nationwide survey by the Educational Testing Service found that out of the 859 colleges surveyed, “the number one cause of student unrest [in the nation] was the war in Vietnam; it caused protests at 34%… of the universities.” In 1970, The Profile ran a retrospective in which three student-government leaders were interviewed and asked to reflect on the academic year. Carolyn Cox, the President of the Student Government Association (SGA) and the Representative Council, stated that “the greatest achievement” of that year was that the Council was the “first body representing Agnes Scott students to go on record in active protest… [against] the war in Indo-China and its continuing atrocities.” Cox’s statement marked a turning point: while other past student associations had anti-war sentiments, they had not asserted them publicly. However, by 1970, members of the Representative Council were comfortable asserting their political opinions. Not all the students at the college agreed; the student body was deeply divided, unable to come to a common consensus. Cox noted that the Council was unable to “[sustain] dialogue with a large portion of the student body.” Finally, Cox notes that the Council’s major failure was its inability to “adequately convey…. the genuine feeling of urgency that students have for genuine academic reform.”

In direct contrast, the alumnae response to campus activism was characterized by fear. Mentions of protest began appearing frequently during the late 1960’s and the early 1970’s in the Agnes Scott Alumnae Quarterly, the alumnae school magazine. In the same year as Cox’s comments, Catherine Marshall-LeSourd, a Christian romance author, wrote an article titled “The Value of an Education.” Marshall-LeSourd derided politically engaged students and portrayed student-leaders as “false prophets.” Marshall-LeSourd’s statement reflects a common perception: that students were naive. Alumnae believed that, unless students received a traditional education, they would be heavily influenced by the opinions of others and be pulled by “every siren’s voice.” Marshall-LeSourd noted that only through intergenerational dialogue would students not reduce Agnes Scott to “educational shambles” like other eastern schools.

Marshall-LeSourd’s response to campus changes highlights the differences between the alumnae and students’ perspectives. When writing this, Marshall-LeSourd was fifty-six years old and graduated more than three decades earlier. Many alumnae believed that students should respect the past, embrace religion, and not change long-held traditions. They tended to be politically conservative and supported the status quo. Student’s in the late-1960’s and early 1970’s did not view institutions with such reverence.

Though the alumnae emphasized the value of a traditional, religious education that had served them well in the past, students were perplexed by the antiquated system and responded with fierce independence, paving new paths for Agnes Scott College. The legacy which these students left was radically different than that of previous generations. Ultimately, they facilitated an active community: engaging with international issues, shifting the school from apolitical to responsive, encouraging active participation and a education that addressed contemporary, global issues. Without these fundamental changes, Agnes Scott would not be the institution it is today.

Written by Samantha Mooney, Intern DeKalb History Center

References

Allen, Beverly, and Pam Burney. Silhouette 1966. LXIV ed. Decatur: Agnes Scott College, 1967. Print.

Armstrong, William et al. “Who’s In Charge?”. Agnes Scott Alumnae Quarterly, 1969.

Dixon, Sharon, ed. Silhouette 1969. LXVI vols. Decatur: Agnes Scott College, 1970. Print.

Gettleman, Marvin E., Jane Franklin, Marilyn Blatt. Young, and H. Bruce Franklin. Vietnam and America: A Documented History. New York: Grove, 1995. Print.

Hamilton, Karen, ed. Silhouette 1967. LXIV ed. Decatur: Agnes Scott College, 1968. Print.

“Looking Back: Three Views of 1970-71.” The Profile [Decatur] 21 Apr. 1971: 2-3. Print.

Marshall-LeSourd, Catherine. “Why a College Education?” Agnes Scott Alumnae Quarterly [1969-1971 (1970): 2-5. Print.

McLuhan, Marshall. “1911-80.” The Montreal Gazette. 16 May 1975. Print.

“NSA – Non-Violent Civil Disobedience.” The Profile [Decatur] 21 Apr. 1971: 93. Print.

“NSA Controlled by Militant Far Left?” The Profile [Decatur] 09 Oct. 1970: 15. Print.

“Shumake Talks Peace.” The Profile [Decatur] 16 Oct. 1970: 25. Print.

“Students Support Confrontation.” The Profile [Decatur] 02 Oct. 1970: 9. Print.