Social Exclusion: Saturday School in Decatur

Between 1902 to 1932 in Decatur, the school week ran from Tuesday through Saturday.

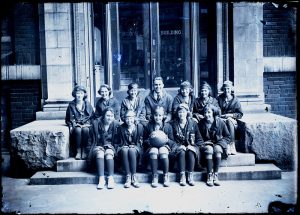

- First Class Decatur High School 1916

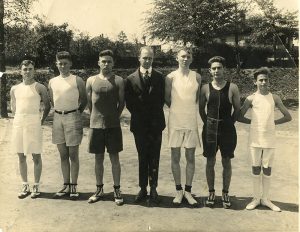

- Decatur High School Track Team 1923

- Decatur High School c 1916

- Decatur High School 1921

“Individuals are prey to institutions in modern mass societies… Individuals can struggle mightily against institutionalized conditions, but without changing the institutions themselves, those efforts will be largely for nought, since people tire, lose focus, forget, and, eventually, give up their ghosts, while institutions share no such limitations.”

― Brian Awehali

Nowadays, students think of weekends as a welcome respite from studying, but, historically, this has not always been the case. Between 1902 to 1932 in Decatur, the school week ran from Tuesday through Saturday. Author Tom Keating proposes that the strange schedule was a method to “discourage Jews from settling in town.” Though no formal statement from the school board has been found, Keating bases his argument on oral interviews. Exploring this perspective highlights the insidious ways that systemic exclusion occurs.

Public school is, in essence, a democratic institution, a pivotal cultural experience that binds disparate populations together. George Washington in his farewell address, recommended that American leaders should “promote… institutions for the general diffusion of knowledge.” An informed and educated populace is necessary to maintain a functioning, republican government. Most Americans have experienced public education. School is, in theory, available to all: rich and poor, athletes and scholars, faithful and areligious, and, more recently, regardless of racial or ethnic background.

In truth, this promise has often failed. School policy is often intertwined with the social problems of the period, often in uncomplimentary ways. Exclusion of minorities is not uncommon. School policy, set by the district board, is a sword and shield: policy can absolve administrators and teachers of responsibility or be used to shut down potential challenges.

In Decatur, from 1902-1932, the standard school week ran from Tuesday through Saturday (with Sunday & Monday as the weekends). Tom Keating conducted over thirty interviews with residents who experienced the policy. They offered the following explanations for the practice:

- Monday was washday

- Harvesting and agricultural practices necessitated the change to accommodate farmers

- “Decatur was just different”

- Agnes Scott College students needed the additional time for traveling

- Monday was deemed by the school board as ‘unsatisfactory,’

- Students were forced to complete work on the Sabbath

- Traveling ministers needed a break

- It was meant to keep Jews out of Decatur

When analyzed, most of the reasons mentioned above can be debunked. The first, the wash day, was due to African-American women and children, who, on Monday, would walk up Clairmont Avenue to grab the wash of prominent white citizens. Keating counters that, given the time period, “it is unlikely that the school district adopted so unusual of a schedule because it was more convenient for black women.” Secondly, Saturday was a long work day, great for familial harvesting as Sunday served as the rest day. So, this reason makes little sense as children would miss school on Saturday to harvest. Though Agnes Scott students were often daughters of local families, it is not clear how they would affect secondary school schedule, especially as most lived in near proximity to the town. Similarly, church officials “expressed confusion” over how ministerial “travel needs could affect [the] public school system.” Monday as an unsatisfactory school day is a thin rationale, and there is no reason homework could not be completed earlier to accommodate worship practices. This brings us to the final reason, that Saturday school was a deliberate policy to keep out unwanted people.

Keating cites oral interviews where subjects were frank about the true cause of Saturday school. Olive Morgan Dougherty, whose mother and aunt worked for the school district, when asked, stated that schedule was meant to “keep out the Jews…” Mr. Ralph Turner, a local mortician, echoed this sentiment as well. Keating asked him, “Why did you go on Saturday, if you know?” Turner replied:

“Everybody said that we didn’t want Jews in the schools… [You heard it] everywhere.”

Andy Robertson, the former mayor of Decatur, also had similar memories: “Talk about being narrow-minded. I never went to school on Mondays in my life. I went on Saturdays. The obvious reason was the Jewish Sabbath. They assumed that if they had school on Saturday…” [Robertson trailed off after this, and changed the subject] This choice had consequences; in the present, less than 1% of Decatur’s population is Jewish. This limited children from being challenged. Emily Boland summed the feeling up well when she said “Our parents and ancestors kept folks from us. They kept us from learning about the world as it is. For that, I am still upset.”

If this premise is accepted as the true motivation for Saturday school, why was this policy only implemented in the twentieth century? The answer can be found in numbers. During this time, Atlanta experienced a massive exponential growth of the Jewish population. In 1880, there were 525 Jews within the city limits. This number nearly tripled by 1916 to 1,500, and, in the 1920’s, ballooned by 700%. By the mid-1920’s, there were 11,000 Jews in Atlanta. The Jewish population was the fourth largest religious congregation in the city. This massive surge was due to greater job opportunities. The IRO (the Industrial Removal Office) sent Jewish immigrants to smaller towns that had pre-established Jewish communities. Many others came on their own, looking for work and the American dream.

Likely, due to local policies, in 1916, there were no Jewish people in DeKalb County. There was fear surrounding the massive influx, and Decatur was not always tolerant. Robert Rampeck, who resided in Decatur, helped re-establish the Ku Klux Klan’s presence in Georgia (Leuchtenburg, Jackson). Several of Keating’s interviewees recalled seeing the white robes of the KKK hanging in closets. The majority of the discrimination that happened in Decatur was done bureaucratically and surreptitiously. Residents felt proud that the town was homogenous and was deeply religious. A 1927 article titled “Why I Live in Decatur” written by Rev. Adiel Moncrief stated that “the people of Decatur in unusually large portions have common racial instincts and common historical traditions, and these things make cordial sympathies.” These feelings were not uncommon in the South, and Decatur was no exception.

As time passed, assimilated Jews, who had lived in America for several generations, began slowly moving into Druid Hills. Some Jewish people came to Decatur. Sam Rittenbaum, his wife, Rose, and his two daughters were thought to be Greek. His daughter, Mollie Goldwasser, recalled that her father said to her:

“Don’t tell anyone that we are Jewish. They don’t allow Jews in Decatur.”

In 1927, the Board of Education moved to have the school superintendent send a colourless ballot out to the district and survey the public for the first time ever (‘colourless’ is a misnomer: the ballot was sent only to the 1,075 local white families who had children enrolled within the district). Out of this number, six hundred responded, and the odds, two to one, were overwhelmingly in favour of a Saturday holiday (423 people wanted the change). Why was the need for a Saturday holiday so great?

Saturday school was detrimental and forced parents to make tough decisions. It lowered student athletic participation as games were commonly held on Friday or Saturday across the state. Due to the timing, children who participated were often absent or came to school with incomplete homework. Afterschool organizations such as Girl Scouts, Campfire Girls, and Boy Scouts held meetings on Saturdays. Familial relationships suffered: working families could not take their children on weekend excursions as work and school schedules differed. Furthermore, inter-collegiate athletics remained an essential father-son bonding activity which encouraged chronic absenteeism. Religiously, it meant that children were “brought to the Sabbath unprepared.” Economically, young men could not be employed by local businesses who hired for weekend help. This additional income was valuable to impoverished families and meant that some young men were forced to choose between work and education.

Administratively, it was cumbersome. Teacher training, when necessary, forced the schools to close on Friday and Saturday. Having a Monday holiday also meant that break schedules had to be adjusted accordingly. The school superintendent, Mr. Glausier, recommended that the schedule ought to be changed. All the above factors made consistent attendance challenging: on the weekdays, absent students averaged around 17% but on Saturday, over 47% of students were absent. This lead to the PTA to observe that “We are paying for five days of school, and we get little more than three.”

The school board was deeply divided over the issue. Though public wanted to change the schedule, the school board vote tied, keeping the practice in place for five more years. This practice had also spread to Emory’s Fishburne school which was the only other place in the country that had the odd weekend. Oral history has attributed the schedule change for the same reasons. Ms. Salter, who attended the school, said:

“Everyone knew that we had millionaires’ children in Druid Hills and that we also had several Jewish children. The area of Druid Hills was often called ‘Jewid Hills.’ We had Saturday school so we wouldn’t have more Jews in our school.”

We often forget the ugly parts of history. Time acts as an erasure. All of us live through history, passing day to day, not knowing how the times that what we live in will be immortalized. Most history is exploring that which we do not know. Historians do their best to reconstruct the past, reconstituting fragments into something cohesive and understandable. The history of Saturday school has resonance in the present. The past deserves our reconsideration, a second chance to question what we know. Restoring other narratives creates a richer tapestry, expanding our understanding of the past, restoring vanished history.

Written by Samantha Mooney, Intern DeKalb History Center

References

“Decatur, Georgia Religion.” Sperling’s Best Places. Accessed June 18, 2018

Jackson, Kenneth T. The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915-1930. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1992.

Keating, Tom. Saturday School: How One Town Kept Out “The Jewish” 1902-1932. Bloomington, Ind: Phi Delta Kappa, 1999.

Leuchtenburg, William E. American Places: Encounters with History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

“New Ku Klux Group Formed in Atlanta; Leader Denies Any Anti-semitism in Movement.” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, July 25, 1930. Accessed June 21, 2018.

Washington, George. Washington’s Farewell Address to the People of the United States. Hartford, Conn, 1813.