Memorial Drive: History from Atlanta to Stone Mountain

The history of Memorial Drive can be seen as a simple story of road construction. However, just under the surface Memorial Drive was dedicated to Confederate memory.

“Another step in the effort of Atlanta and Georgia to honor the memory of the heroes of the confederacy” The Atlanta Constitution, February 2, 1930.

By Marissa Howard, Programs and Membership Coordinator

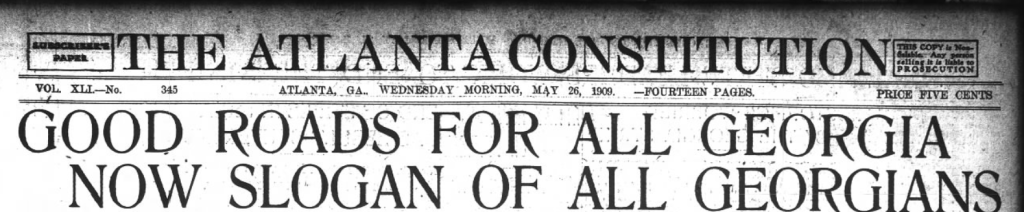

In grappling with DeKalb’s remembrances of the Confederacy, communities have removed statues (the Confederate monument in downtown Decatur), renamed roads (Confederate Avenue), and remained unsure about a granite carving of Lee, Jackson, and Davis. But why have we not considered the history and name of Memorial Drive? It is a 15-mile road flanked by two jails that begins at Georgia’s gleaming gold “Capitol of Dixie” dome and ends at Stone Mountain’s Confederate Hall.

Is Memorial Drive nothing more than the road’s destination or is it a driving route of Confederate memory? Do you know the history of this memorial or is it a monument hiding in plain sight?

Where did it all begin for Memorial Drive?

What led to Memorial Drive’s creation and what was its purpose? It might seem obvious, but the history, and step by step process of its creation, shows a straightforward and well-connected path that is lost to many today.

This highway was conceived, created, and built as a journey to the Confederacy’s mecca. A pilgrimage site for the world, carved in eternal granite.

Intersection of Moreland and Memorial Drive, looking east.

“A highway project of tremendous significance….from both spiritual and material viewpoints.”

-The Atlanta Constitution, March 1 1925.

The Beginning of Memorial Drive, 1860s-1916

Memorial Drive began as East Fair Street, one of the first streets in Atlanta. It was named for the 19th century fairgrounds in Grant Park, which appeared on maps as early as the 1860s. East Fair Street led from the downtown commercial area to residential neighborhoods.

Suburban growth in Atlanta and DeKalb County in the late 1890s led to the creation and expansion of neighborhoods such as Grant Park and Edgewood. This push for development further east extended East Fair Street to the edge of Atlanta City limits at Candler Road, allowing inclusion of the neighborhoods now known as East Lake and Kirkwood.

Further east, between Atlanta, and what would become Stone Mountain Park, lie the communities of Decatur, Ingleside (precursor to Avondale Estates), and Stone Mountain.

East Fair Street, and nearly every other road in the city, was unpaved and in poor condition. It was not until 1891 that the Georgia State Legislature allowed counties to levy a tax for road building. Paved roads were unusual, as paving required property owners to agree to bear the cost of half the project.

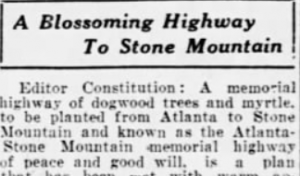

East Lake Drive paved. The Atlanta Constitution, September 12, 1911.

Wealthier neighborhoods, such as East Lake or Druid Hills, paved roads when residents or developers privately funded and organized paving. There were very few public charter roads; in 1912, Fulton County boasted one, Adamsville Road. Living on a paved street was a luxury. It projected status, and so, it was in the best financial interest of developers, builders, and counties to have “Good Roads.”

“Good Roads,” 1890-1920

The Atlanta Constitution often ran competitions for pathfinding missions across Georgia with rewards. Enthusiasm ran rampant according to the newspaper. The Atlanta Constitution, May 26, 1909.

The Good Road Movement (1890s-1920s) was a political special interest, with strong lobbying. In keeping with the Progressive Era, it presented itself as a movement for social improvement and greater transportation efficiency. Endorsed and fueled by automotive clubs, journalists, and farmers’ groups, the Good Road movement would seek to build and improve automobile infrastructure. Newspapers, such as The Atlanta Constitution, would host contests for pathfinding missions to charter new routes and roads to connect Georgia cities, or tourist attractions.

Large-scale routes such as the Lincoln Highway (NYC-San Francisco) or Bluegrass Highway (Kentucky) were created, and were a financial benefit to the small towns and businesses along the routes. Lobbying efforts made by small towns and attractions could ensure their community be included on these routes.

The Good Roads Movement gained national attention and succeeded with President Wilson signing the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, which provided financial assistance to states for road building.

It is important to note that these roads, routes, and automobiles were built for and benefited a mostly White middle and upper class. Affordable cars, such as the Model T, gave more middle class citizens freedom from segregated trolley and rail cars. The automobile provided many a means of escaping the city on new highways, and driving itself became a leisure activity. Meanwhile, it was nearly impossible for Black vacationers to travel far distances. With strict segregation laws preventing everything from visiting restaurants and hotels, to even towns, Black travelers would find obstructions at every point in their journey. While Black tourists were being denied entry to bathrooms at gas stations, white tourists were actively seeking new destinations for their travels.

The UDC Makes a Mark, 1909

In the South, where much physical history was destroyed during the Civil War, women’s groups, particularly the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), took the opportunity to construct a “Lost Cause” narrative of history. They sought, through monuments sponsored by numerous local chapters, to promote a proud history of the South that could neatly avoid the subject of Confederate defeat.

During the period of the Good Roads Movement (1890-1920), the majority of new monuments were dedicated to the Confederacy1. Monuments were installed nearly everywhere across the United States, even in locations that never saw battles during the Civil War. It was not historical accuracy that motivated the UDC to create these monuments; they sought to defend the principals of the Confederacy while downplaying slavery’s role in the Civil War. The UDC offered glory to the Confederate dead, which in turn elevated their political profile. It seemed they wanted every corner of the United States to have reminders of the Confederacy. This effort did (and continues to) change the memory of the past. These newly erected monuments, as points of interest along routes, also created a sense of pilgrimage for the privileged.

One particular route created by the UDC was the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway (1913-), which ran transcontinental from the Atlantic to the Pacific. A remnant of this route can be found on the corner of East Lake Drive and Ponce where a small stone marker still stands.

The top photo shows the unveiling at Fort McPherson. The two other locations which were ceremoniously revealed were College Park, and the corner of East Lake Drive and Ponce De Leon, which is still in place today (bottom photo). A fourth marker was located at Agnes Scott College at the corner of S. McDonough Street and East College Avenue. It was removed, but can be seen in past view.

The UDC was a powerful organization, which used their influence for fundraising and beautification. These women were doing more than laying wreaths and cutting ribbons. They were the wives, hostesses, and firebrands that got conversations started.

The largest monument the UDC contemplated would be the 1,700 foot granite monolith, Stone Mountain. Atlanta UDC chapter president Helen Plane pushed the idea of the Stone Mountain Carving in 1909, leading this charge to create the “temple” of the Confederacy.

Stone Mountain, Eternal Temple to the Confederacy, 1909-1927

While Helen Plane may have suggested using Stone Mountain as a memorial, it was an editorial by John Temple Graves (The Atlanta Georgian) that connected the sheer size and scale to something of a divine inspiration.

From an Editorial in 1914.

“It is a wonder that it has not been suggested and realized many years ago. Just now while the loyal devotion of this great people of the South is considering a general and enduring monument to the great cause ‘fought without shame and lost without dishonor,’ it seems to me that nature and Providence [emphasis added] have set the immortal shrine right at our doors, and that we have only to open our eyes to see it, and our hearts and hands to make it wonderful.”

He goes on

“Stone Mountain is distinctly one of the wonders of the world. Its glories have never been fully appreciated or utilized by the people who see it every day. It is a mountain of solid granite one mile from its summit to its base. Much of Atlanta has been builded [sic] from it, and there is enough left to build ten more Atlantas [sic] without touching the lofty spot that is nearest to the sun.”

This monument would be the “worlds greatest achievement” and “eternal granite.”

But who owned this divine land? Who held the keys to make Stone Mountain a local Mount Parnassus? The answer to this question: the Venable family.

In 1887, Samuel and William Venable purchased Stone Mountain from the Stone Mountain Granite Corporation and continued selling this lucrative product while gaining wealth and power.

Five years from the initial call to action to make a monument, the Venables began working with the UDC and the State of Georgia to sell a portion of the mountain for that purpose. The State of Georgia would work with the UDC to raise funds for the “finest memorial in the world to the Confederated Cause.”3

In 1915, a rekindled Ku Klux Klan began to use the “eternal granite” for newly inspired rituals. Their doctrine spoke of “divine Providence”; that a knighthood of white men have a providential, or divine right, to lead in all areas of society. This concept, central to KKK beliefs, was displayed with burning crosses and costumes (the white hooded robe) on the top of the mountain, with Sam Venable present.

The Atlanta Constitution, November 28, 1915.

The relationship between the State of Georgia, the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the Venables, and the KKK, was a cooperative one. They had their location, and sculptor, but they wanted more tourists.

Granite Highway Takes Shape, 1914-1925

The first car scaled up Stone Mountain in 1909, and was reported nationally in an article in the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune.4 Tourism didn’t slow down, it boomed.

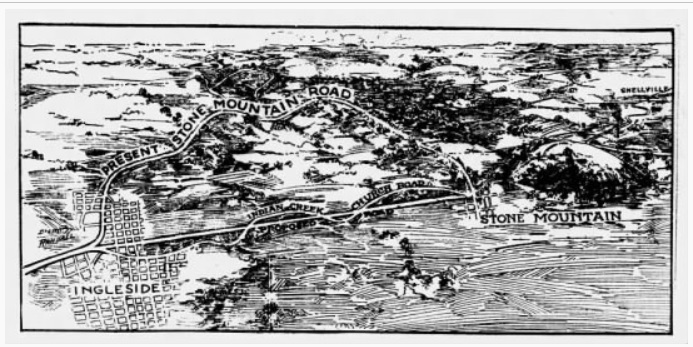

Thousands of cars and tourists were flocking to Stone Mountain, and in January of 1914, the Atlanta Convention Bureau proposed two routes for the Stone Mountain Road from Decatur to Stone Mountain. The route they chose paralleled the existing railroad, and improved the smaller already existing road, which today is East Ponce De Leon Avenue.

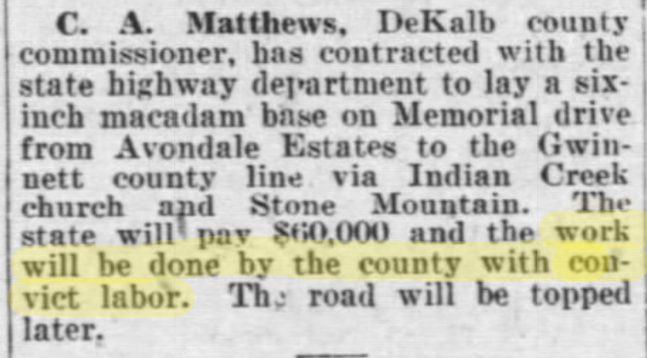

DeKalb County’s total cost for the nine-mile project was $90,000, and the Stone Mountain Quarry provided broken stone used in construction. Property owners along the route also paid half, bringing the entire cost of the project to $180,000 (about $4,000,000 today). An estimate of the cost of such a road in 2021 would be about $1,000,000 per mile for a total of $9,000,000. The difference – $5,000,000 in 2021 – was made up by Georgia’s system of convict labor for which there was very little cost to the local governments.

Convict Labor building Georgia’s Roads, 1890s

“The chain gangs originated as a part of a massive road development project in the 1890s. Georgia was the first state to begin using chain gangs to work male felony convicts outside of the prison walls. Chains were wrapped around the ankles of prisoners, shackling five together while they worked, ate, and slept. Following Georgia’s example, the use of chain gangs spread rapidly throughout the South.”

Walter Wilson, Forced Labor in the United States, 1933

The Atlanta Constitution promoted the use of forced labor in the development of Georgia’s “Good Roads.” In May of 1914, the newspaper stated “all that is needed is the labor” to complete the Granite Highway/Stone Mountain Highway in time for the American Road Congress, which would be held in Atlanta in late 1915.5 DeKalb County requested the loan of 50 convicts from Fulton County to be used in conjunction with all the convicts of DeKalb County to finish in time for the Road Congress. DeKalb County would “house, feed and maintain the borrowed convicts.”

Convict labor, or slavery under a different name, was seen as such a benefit to the state road system and tourism that it was discussed at length and studied in the 1915 American Road Congress. Prisoners were viewed as an asset for infrastructure that could be used anywhere as needed.

“On the other hand, the members of the Congress, in addition to their mapped – out work, we will have a valuable opportunity to study the effects of and note the results obtained from the county system of working convicts furnished by the state. There is a growing disposition on the part of other states to follow Georgia’s example in putting the felony convicts on the road; and this convention will bring here many state officials directly interested in this subject of the road problem.”The Atlanta Constitution, Nov. 2, 1914

“For twenty years The Constitution [newspaper] has led in the effort and the movement to have the convicts of the state put on the public roads. This was at last achieved by the action of the legislature in 1907, and the year following saw 4,000 or more state convicts engaged in this splendid constructive service in Georgia. Thus Georgia’s system of road building has been revolutionized until today there Is not a state in the union in which any better work is being done.” The Atlanta Constitution, Nov, 2, 1914.

In 1932, Richard Elliot Burns’ autobiography and Hollywood movie of I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang! exposed the public to the brutal and inhumane treatment of Georgia’s convict labor system. In his book, Burns describes being placed in iron restraints and forced to work along Roswell Road breaking up rocks with a sledge hammer and spreading the gravel on the road. Although reform did come eventually, chain gangs continued to operate on roads including Memorial Drive.

Convict labor building Memorial Drive. The Atlanta Constitution, April 12, 1933.

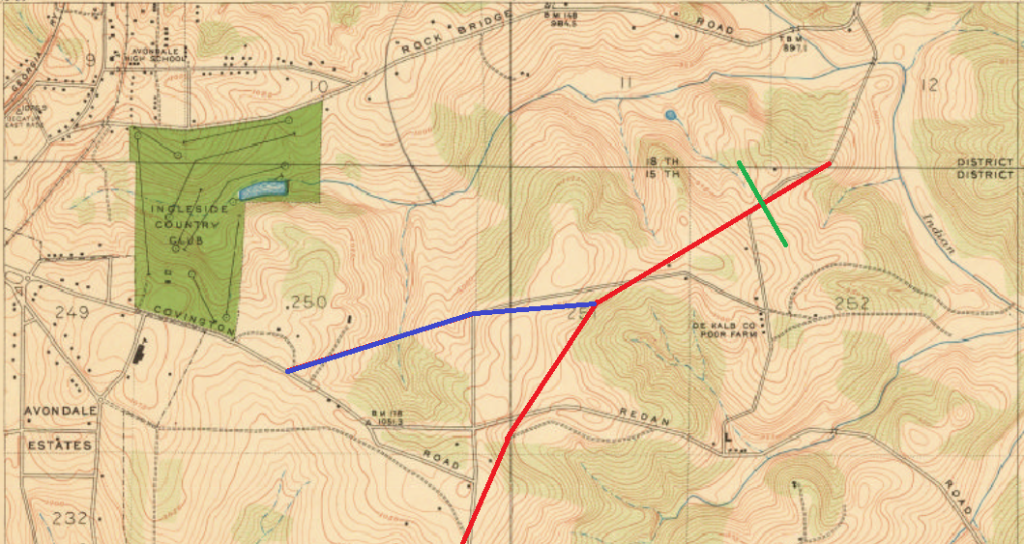

Chain gangs were “housed, fed, and maintained” in prison camps or farms, like the Atlanta Prison Farm on Key Road. However, another prison camp was located on Camp Road on the site of the DeKalb County Pauper Farm.

Pauper farms, or poorhouses, were local government run facilities where the elderly, disabled, or sick could live and work if they were able. Residents were not permitted to leave the grounds and these sites were often a source of complaints for deplorable conditions. They were often located on or near prison camps and utilized the same infrastructure. Prisoners with minor offenses or short sentences would live and work the farm, or other labor projects as needed.

1915 Map of DeKalb County. Showing Decatur, Ingleside (Avondale Estates) and Scottdale. Circled area shows Poor Farm. Image Source: DeKalb History Center Archival Collection.

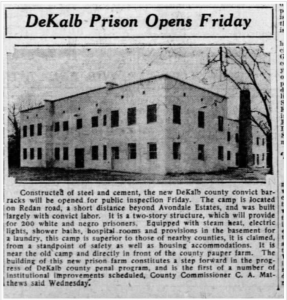

In 1932, the first “institutional improvement” of DeKalb’s penal program was opened on this site – steel and cement convict barracks. Prisoners provided the labor for their own concrete prison.

Newly built and ready to open in 1932. Dealing with negative publicity, this camp was said to be “superior to those of nearby counties.” The Atlanta Constitution, February 11, 1932.

The prison was located at the intersection of Camp Drive and Camp Way. After it was no longer used to house convicts, it was home to various DeKalb County offices and was demolished around 2015.

Photo on top, 1970s. Photo on bottom, 2008. Source (T): Vanishing Georgia, Georgia Archives, Morrow, Georgia Source (B): Source Link

The Pauper Cemetery, located in a fenced area between the DeKalb County Road and Drainage Building on Camp Road, and the service road behind the DeKalb County jail. Photo undated. Image Source: Pauper’s cemetery photos, Cemetery subject files, DeKalb History Center Archives

Mountain View Cemetery, originally known as the DeKalb County Pauper Farm Cemetery. DHC Collections, Photo Undated

A New Route, 1921-1934

“A highway project of tremendous significance . . . from both spiritual and material viewpoints”

The Atlanta Constitution, March 1, 1925.

The Stone Mountain-Decatur Highway (today’s E. Ponce de Leon Avenue) was completed in October of 1921. This highway was 24 feet wide, which by today’s standards is about a two lane road. Although it was new, this small road could not handle the influx of tourists and so a new “more direct road was needed.”. As tourism continued to boom in the 1920s a new “Stone Mountain Highway” was planned.

- April 6, 1924

- March 1, 1925

- April 6, 1925

- October 4, 1925

By 1924, the first meeting of the “Stone Mountain Highway Route Association” was held and a year later a full spread advertisement appeared in The Atlanta Constitution for a proposed new highway.

They listed several advantages of a new highway.

- Provide two improved driveways to the memorial.

- Bring the memorial, by means of the short cut, three miles nearer Atlanta.

- Create a highway that presents a clear view of the mountain as an inspiring goal of travel through most of its stretch.

- Above all things, increase the facilities for reaching the mountain, which are, each day of the memorial’s development, becoming more essential.

The Stone Mountain Memorial Association (SMMA) was a fundraising organization founded and presided over by Helen Plane, Honorary President of the UDC. This organization formed in 1917, and by 1924 was a full blown lobbying and fundraising organization with Hollins Randolph presiding. The organization had deep ties in Atlanta and DeKalb County society and government from the beginning. And by 1924, SMMA reached to the United States government with the eventual minting of the Stone Mountain Half Dollar in 1925. This was to be a national fundraiser for the monument and was designed by Gutzom Borglum.

The Stone Mountain Route Highway Association, led by Atlanta Hotel magnet Frank Reynolds and L. Y. T. Nash, Road Commissioner of DeKalb County, was founded early 1924 with the intention of creating an Atlanta to Monroe state highway.

The Stone Mountain Carving was in crisis behind the scenes from 1924-25. They were running out of money and despite the best efforts of advertising and the Memorial Coin fundraiser, work on the carving had to stop. Fighting within the organization led to public squabbles between SMMA president Hollins and Constitution editor Clark Howell, Sr. The sculptor, Gutzom Borglum (who briefly lived in Avondale Estates), became embroiled in the fight and was fired by the SMMA in 1925.

Avondale Estates Gets Involved, 1924

George F. Willis, a well-connected Atlanta businessman and member of the SMMA saw an opportunity in a sleepy community called Ingleside. In 1924, he purchased the 950 acre plot of land would become Avondale Estates and “away from the noise and dirt of the city but close to the heart of things in minutes.” 6 This new highway to Stone Mountain would run directly through it.

On January 19, 1924 the 117th anniversary of Robert E. Lee’s birth, the events surrounding the unveiling of General Lee’s head on the “precipice” of Stone Mountain read as a “who’s who” of Atlanta society and government. Six southern governors attended and were hosted in the homes of SMMA members for a short rest before arriving at the Piedmont Driving club for breakfast and were then to have lunch on the carving itself. George Willis, hosted the governor and first lady of North Carolina.7

But in 1928, carving on the mountain ceased; the same year George Willis became the president of the Stone Mountain Memorial Association. The original agreement from the Venables gave SMMA 12 years to finish the carving and that time period had ended. The carving was on hold, but road creation was still in full swing. Perhaps tourists and publicity might get the carving restarted.

A Different Approach to Memorialization, 1925

In late 1925, The Touring Bureau of The Atlanta Constitution invited Mr. C. Frank Dunn, managing director of the Lexington [KY] Automobile Club and Blue Grass Tour, to visit local sites and appointed him Kentucky’s publicity director of the Stone Mountain Memorial Coin drive and highway tourism.

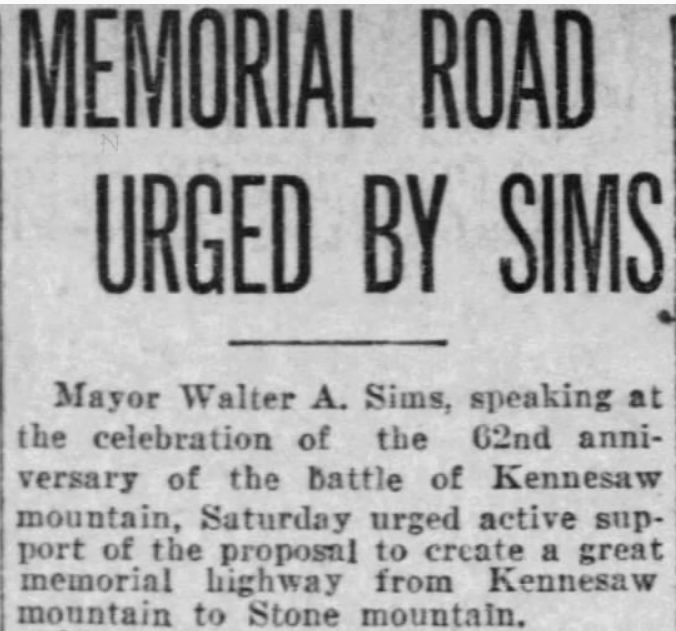

And in 1926, a new approach to memorialization emerged: a highway from Kennesaw Mountain to Stone Mountain.

The Atlanta Constitution, June 27, 1926.

“To connect these two great projects with a magnificent boulevard, say 110 feet wide, would, in my opinion, be of great benefit to both, and to the general public.

Charles J. Metz, President of the Audit Company of the South and Stone Mountain Memorial Association Official. June 1926.

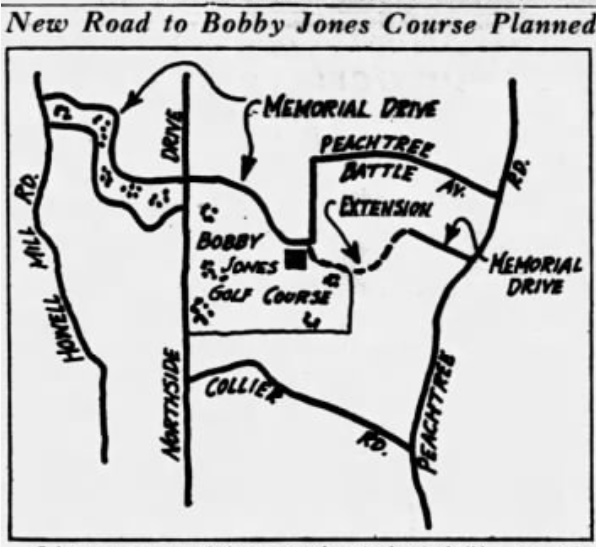

An announcement regarding plans for the new Bobby Jones Course and plans to connect it to Stone Mountain. The Atlanta Constitution, August 30, 1930.

A new plan emerged to connect Kennesaw Mountain to Stone Mountain in the area of Peachtree Battle Neighborhood in South Buckhead. The Atlanta Constitution, September 3, 1936.

Blue and Gray Memorial Highway Between Mountains, The Atlanta Constitution, July 10, 1938.

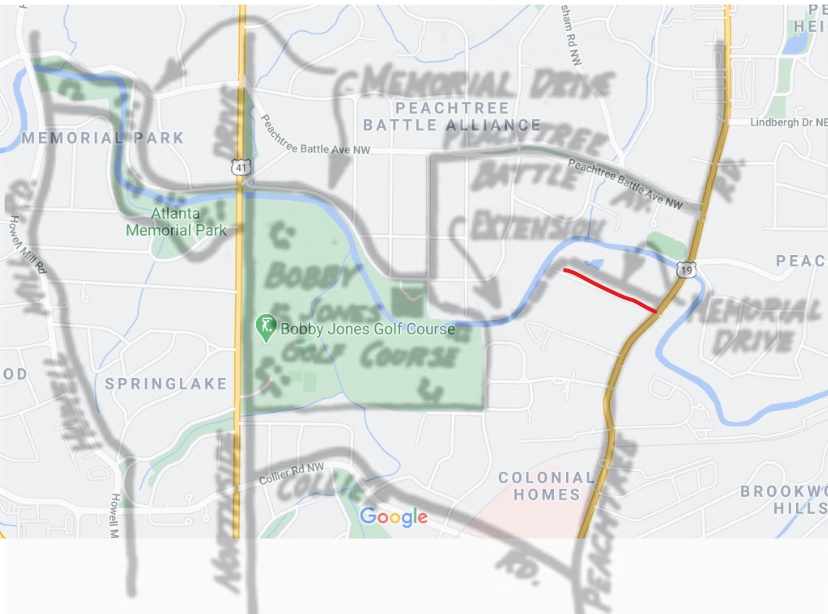

While the large scaled highway never officially came into existence, there does exist a Peachtree Memorial Drive, just off Peachtree road. The park area in the above 1936 map is Atlanta Memorial Park. Sam Venable also donated granite for the construction of this road and Atlanta Memorial Park.

Current map of Peachtree Battle Neighborhood with the 1936 map overlay. Peachtree Memorial Drive is marked in red.

Memorial Drive Breaks Ground, 1927

On October 16, 1927, crews broke ground on the “Stone Mountain Memorial Drive.” The groundbreaking was quite the affair, led by the Stone Mountain Memorial Association. This portion of the route was the extension from Avondale Estates to Stone Mountain.

Groundbreaking of Memorial Drive. Atlanta Constitution, October 16, 1927.

Meanwhile, the final and missing link was being planned from Candler Road to Avondale. We can see the end of East Fair Street in Atlanta in the map below from 1928.

The final connecting portion in blue was the extension from Fair Street just past Candler Road. The red star is Belvedere Park.

An announcement came in February 1930, that East Fair Street would officially be renamed to Memorial Drive. This drew the memorial line from Georgia’s state capitol to the “eternal temple to the Confederacy.”

“Another step in the effort of Atlanta and Georgia to honor the memory of the heroes of the confederacy”

The Atlanta Constitution, February 2, 1930.

East Fair Street is renamed Memorial Drive to “honor the memory of the heroes of the Confederacy.” The Atlanta Constitution, February 2, 1930.

Intersection of Whitefoord Avenue and East Fair Street. The Atlanta Constitution, August 22, 1930.

Atlanta-to-Athens Stone Mountain Memorial Highway opens in 1939. The Atlanta Constitution, May 13, 1939.

The Memorial Lives On

Segments of preexisting roads were simply renamed to stay consistent with the route that led to Stone Mountain. But the evidence is clear, Memorial Drive was named for its destination, Stone Mountain’s Confederate Memorial Sculpture. Obscured by modern development, the view and history have quietly disappeared. But drive a little further east and the vision reemerges. The rusty and faded road signs still mark the mileage to Stone Mountain, leading some pilgrims directly along their path.

______________________________________

Web Sources:

https://archive.org/details/forcedlaborinuni00wilsrich

https://www.ajc.com/news/local/post-slavery-south-chained-hard-labor/SYsc78V0s3PwCSx2RVhmpN/

Archival Sources:

Howard, Fred A. “History of DeKalb County Police Department .” DeKalb History Center Archives , DeKalb History Center Archives , 1976

1: https://www.splcenter.org/sites/default/files/com_whose_heritage_timeline_print.pdf

2: https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.01403900/.

3: Lexington Herald-Leader, Lexington, Kentucky, 26 Jul 1914.

4:Star Tribune, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 21 Nov 1909.

6: The Atlanta Constitution, Atlanta, Georgia, 25 May 1914.

7: The Atlanta Constitution, Atlanta, Georgia, 26 Apr 1925.

8: The Atlanta Constitution ,13 Jan 1924.