Elias Nour: “The Old Man of the Mountain”

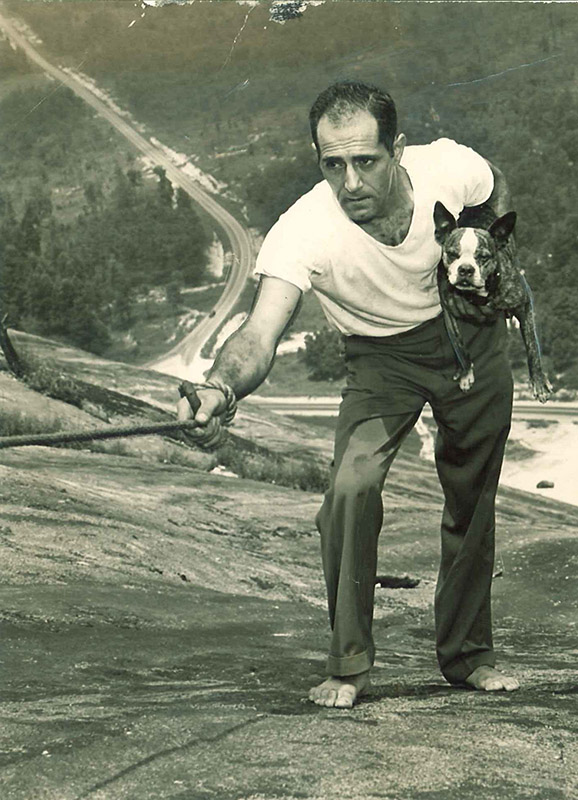

Elias Nour: the “Old Man of the Mountain”, rescuer to many on Stone Mountain.

Stone Mountain has been standing in DeKalb long before the county was apportioned and named. It has drawn the attention, wonder, and curiosity of people from around the world. Visitors are able to climb up a hiking trail for exercise, to take photographs, have a picnic, or simply to marvel at the view from the top. Taking a walk up the mountain is straightforward; one need only follow the yellow lines up, and closer to the top a fence keeps hikers safe from getting trapped on steep sides or falling down to the bottom.

However, it was not always such a safe endeavor to take a trek up the mountain. Before Stone Mountain was turned into a public park, there was no incentive to have a marked trail. The fence around the top of the mountain was falling apart, and had only been placed to keep people from throwing rocks down on workers carving the monument back in 1923.

Fence atop Stone Mountain

So it was inevitable that people, either lost or hoping to get a better look at the carving from the top, would lose their footing and find themselves stuck, perilously close to falling. Salvation for these people came in the form of a man: Elias Nour.

A son of immigrants from Lebanon that moved to Stone Mountain in 1924, Elias had the good fortune of growing up with the mountain as his playground. He came to know the mountain like the back of his hand, able to “play Tarzan” to his heart’s content. This knowledge he acquired ended up leading him to make his first mountain rescue at the young age of thirteen.

From that point on he continued to save people that needed help, amounting to a total of thirty-six people and six dogs. One particular rescue, of a student from Georgia Tech, earned Elias Nour the Carnegie Medal – an award for individuals that have risked their lives to save others. Using several ropes bound together, one of which was frayed and rotting, Elias was lowered down the mountain face to grab the student in front of a crowd of onlookers.

Elias Nour preparing ropes

His daring made itself known in other ways too. Saving people was not the only thrilling act he performed on the mountain. In 1934 he participated in the “Suicide Derby”, a race down the vertical side of Stone Mountain. Utilizing the left over stakes from the initial carving of the monument as well as some rope, Elias managed to set a record of four minutes and fifteen seconds.

Elias Nour on Rigging

At the age of nineteen, in front of a crowd, Elias set a car named “Depression” that was painted with anti-Depression slogans on fire and sent it down the side of the mountain. He repeated this exciting act in 1942 only this time the car was painted with slogans against war enemies. This latter event was done to raise scrap rubber for the US military, setting rubber as the admission charge for spectators. About a ton of scrap rubber ended up being collected.

Elias Nour driving “Depression”, 1933

No one could deny that Elias was both fearless and quick to help when and how he could. It was no wonder that even up until 1963, as he was approaching his 50’s and dealing with arthritis in his hands that kept him from hauling rope, he was still turned to for help. As he grew older, it became increasingly difficult for Elias Nour to continue coming to the rescue. In addition to arthritis, back troubles after an accident meant that he no longer felt completely safe and sure-footed on the steep mountainside. However, by that point with his help and guidance, lines for the hiking trail had been painted down and in 1963 he directed the installation of a fence. The safety that visitors to Stone Mountain feel today as they hike the granite trail, can be attributed to Elias Nour.

His heroism and knowledge were honored at an event in 1988 by the Stone Mountain Memorial Association and Georgia’s Secretary of State. It was five years later that Elias Nour, the “Old Man of the Mountain”, passed away at the age of 79.

Elias Nour Rescues a Dog

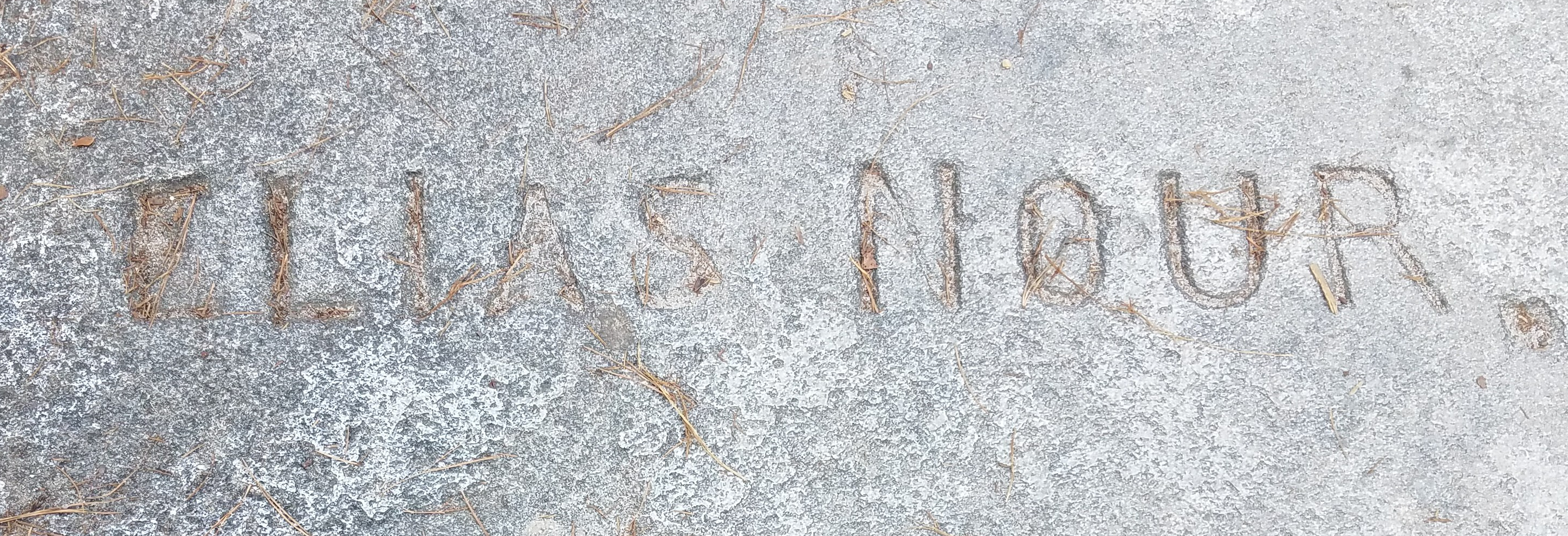

In the present day, if you happen to feel the urge to visit Stone Mountain, you might notice a street named Elias Nour Drive if you come into the park via Stone Mountain village. And if you decide you want to retrace his footsteps up the mountain, and you look very carefully, you might notice his name carved into the granite mountainside that he knew so well.

“Elias Nour” carved into Stone Mountain

by Sophia Malikyar

Information gathered from:

DeKalb History Center Archives

Stone Mountain Guide