The Monument That Sparked A Movement

by Rebecca Selem, Exhibits and Communications Coordinator

“A monument is not history itself; a monument commemorates an aspect of history, representing a moment in the past when a public or private decision defined who would be honored in a community’s public spaces.” – American Historical Association, August 2017.

Beginning on June 18 and ending on June 19 (Juneteenth), 2020, the Confederate monument, which stood in front of the Historic DeKalb Courthouse for 112 years, was removed. To some, this course of action came as a surprise, but to many, the removal was long-awaited and necessary for our collective social progress.

In order to understand why the monument was removed, we must go back to the early 1900s and put into context why it was erected in the first place. We can no longer ask the organizations that commissioned the monument what their true intentions were for its creation and location, but we can analyze events of the time period to better understand what circumstances may have led to the production of the monument. In researching the background behind this local monument, we also see why so many other Confederate memorials were created simultaneously across the nation.

Historic markers rarely include contemporaneous reasons explaining why they were installed. There may be some written reasons, but markers are greatly influenced by the events of the time period – and these events are omitted in the text. DeKalb’s monument was installed two years after the Atlanta Race Riots and seven years before the reemergence of the Ku Klux Klan on Stone Mountain. Well after the Reconstruction era, many in the South sought to venerate the “Lost Cause” and turn back social progress through Jim Crow laws. The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) was very focused on promoting the “Lost Cause” version of the Civil War that minimized slavery’s central role and promoted the Confederacy as heroic. That national organization had committees and publications to set standards for history books to support their vision of the Civil War, including assertions that the Confederacy did not start the war, that it wasn’t begun over slavery, and that enslaved people were treated well.

The final push for a local Confederate monument began on Robert E. Lee’s birthday, January 19, in 1907 with the formation of the DeKalb Confederate Memorial Association. The association was made up of members from the C. A. Evans Camp of Confederate Veterans and the Agnes Lee Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (which had failed to raise enough money to buy and install a monument by themselves), and other interested locals. The monument is estimated to have cost $3,000, with money allegedly raised from White and some Black schools in the county, along with contributions from citizens and businesses. However, the Association’s records have never been made public. The monument was designed by the Butler Granite Company of Marietta, Georgia.

The unveiling of the monument on April 25, 1908, in Decatur, Georgia.

This obelisk was dedicated on April 25, 1908. Its unveiling had been planned for November 9, 1907, but when workers were lifting the obelisk onto the base, some of the ropes snapped and it broke into two pieces upon hitting the ground. Prior to 2020, the obelisk was moved twice. The monument was moved a short distance by the City of Decatur in 1937 – probably due to road and sidewalk work. And in the 1970s, it was moved fifteen feet north of that location to make way for the Decatur MARTA line.

Worker moving the monument to make way for the Decatur MARTA line, circa 1975.

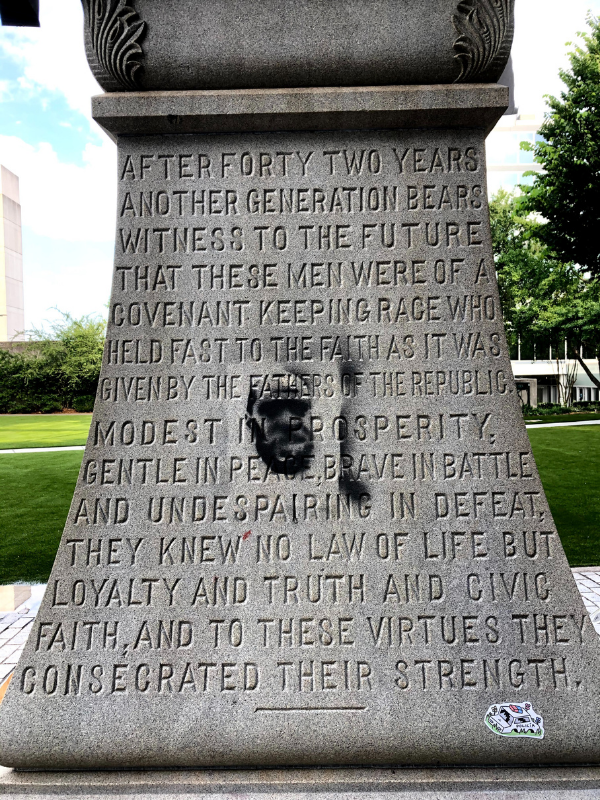

Its inscription, wrapped around the four sides of the base, was written by Hooper Alexander, Sr., who was a prominent Decatur lawyer and later a U. S. Senator. The inscription reads:

East side: After forty two years another generation bears witness to the future that these men were of a covenant keeping race who held fast to the faith as it was given by the fathers of the republic. Modest in prosperity, gentle in peace, brave in battle and undespairing in defeat, they knew no law of life but loyalty and truth and civic faith, and to these virtues they consecrated their strength.

South side: Erected by the men and women and children of DeKalb County, to the memory of the soldiers and sailors of the Confederacy, of whose virtues in peace and in war are witnesses to the end that justice may be done and that the truth perish not.

West side: How well they kept the faith is faintly written in the records of the armies and the history of the times. We who knew them testify that as their courage was without a precedent their fortitude has been without a parallel. May their posterity be worthy.

North side: These men held that the states made the union, that the constitution is the evidence of the covenant that the people of the state are subject to no power except as they have agreed that free convention binds parties to it, that there is sanctity in oaths and obligation in contracts, and in defense of these principles they mutually pledged their lives their fortunes and in their sacred honor.

At first glance, the inscription seems merely poetic, but it conveyed an interesting message to the people of DeKalb County that would correspond with the events of the time period. Most modern readers particularly object to the phrase, “a covenant keeping race.”

At the turn of the century, the United States was thriving with booming industries and the beginning of the automobile’s rise in prominence. However, the social climate was a different story.

The end of the Civil War brought peace to the nation, but without reconciliation. Even as the conflict came to an end and African Americans were released from bondage, white supremacy remained ingrained on our social order. Working conditions were stagnant, so beginning in 1916, African Americans began migrating from the South into the North and to urban centers throughout the country, hoping to find a new way of life. The influx of Black workers in these areas caused competition for jobs and racial tensions followed. Many White people felt that they were superior over any Black person, regardless of education or social standing. At the same time, Jim Crow laws were increasing; these laws curbed the success of Black people by enforcing segregation and limiting personal freedom. In total, 27 segregation-related laws were passed in Georgia between 1865 and 1958. They were designed to replicate slavery as much as possible in spite of the 13th Amendment. Among other things, these laws stopped Black Americans from voting, created the convict leasing system, and attempted to strip Black citizens of their constitutional rights.

Tensions continued to rise in Atlanta, and swelled to their worst in 1906. In that year’s gubernatorial campaign, both candidates ran on extremely racist platforms in order to gain popularity with White voters. Hoke Smith, one of the candidates, was particularly harsh with his campaign rhetoric and worked to invoke fear and hate from his followers. He blamed African Americans for Georgia’s problems, and insisted that Black men were committing crimes against White women. On top of that, newspapers across the city were running sensationalized articles that also accused Black men of heinous crimes, with little to no evidence to back up their claims. Black and White businesses were intermingled downtown, and prosperous stores, such as Alonzo Herndon’s barber shop, enraged Whites even further. The swell of tension finally burst on September 22, 1906, when a mob of about 10,000 White men marched into the city and attacked any Black person they could find, ultimately killing between 12 – 25 people. They burned homes and businesses, and terrorized the Black community. The riot lasted two days, and in its wake, the city was more divided than ever. The Sweet Auburn district of Atlanta was formed after the riots. Black businesses segregated themselves to one area for safety. From the 1890s to the 1920s, race riots such as this one erupted all over the country, instilling fear in Black citizens and wiping out their property and wealth through death and destruction. In addition, individual lynchings were adding to the intimidation and death toll across the South.

How were Jim Crow laws and Atlanta’s race riot related to DeKalb’s Confederate monument? While the monument was in part commissioned to remember those who lost their lives fighting for the Confederacy, this was not its only purpose.

A public gathering taking place at the courthouse. Circa 1950s.

Historic Confederate monuments were erected during three general time periods. From the end of the war to the early 1880s, monuments were generally built for the purpose of honoring those who fought in the Civil War. From the 1880s to the 1940s, monuments were built for additional reasons. With a tremendous spike occurring in 1911, countless Confederate monuments were erected in many southern states, but not for the reason you might think. From the 1880s to the 1940s, there was a rise in popularity of Jim Crow laws and white supremacy ideals to keep the power in the “right place.” A majority of monuments commissioned in this span of time were placed in very public places such as on the grounds of a government building, while in previous decades they had been confined to cemeteries or battlefields. This time period was also when Confederate soldiers and their families were aging. Private groups like the UDC wanted to honor these soldiers, but also promote their sanitized and faulty version of history. The end of World War I brought another surge of white supremacy when Black soldiers came home. Despite their sacrifices fighting for our country, they were again treated as inherently inferior when compared to Whites.

The next wave of Confederate monuments popped up during the 1950s and 1960s. Monuments went up to mark the anniversary of the southern defeat while simultaneously opposing the Civil Rights Movement surging through the country at the time. Smaller waves of monument building have continued almost up to the present.

From 1869 – 2015, at least 830 monuments to the Confederacy were erected across the United States. Hundreds of these monuments were sponsored by the UDC and hundreds were also built on courthouse grounds. So, in 1908 when the DeKalb marker was installed, riots and lynchings terrorized Black citizens across America and Jim Crow laws limited where Black citizens could go and what they could do. Confederate monuments were erected all across the United States, but not in cemeteries or on private land. Instead they were installed in prominent locations, often the center of town, to remind anyone walking by that the legacy of the Confederacy was still incredibly important to the monument’s sponsors. While some still debate the causes of the Civil War, Confederates were willing to fight and die in order to preserve the right to enslave humans, and that cannot be overlooked. And the same organization that was so instrumental in raising funds for and erecting these monuments, the UDC, also sought to promote the belief that the war was for states’ rights.

Photograph taken of the DeKalb County courthouse sometime between 1908-1916.

Shape and Symbolism

The obelisk form can be traced back to the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt (c. 3150 – 2613 BCE). Its Egyptian name is tekhenu, meaning to pierce, but the Greeks called it obelisk, meaning needle, or a spit used for cooking.

Other cultures around the world also built obelisks, but only the ancient Egyptian obelisks were carved from monolithic stone, which was often red granite. In Egyptian culture, these structures usually commemorated an individual or an event, while also representing the benben, which is described as the “primordial mound that the god Atum stood at the creation of the world“.

Obelisks are ubiquitous and widespread. They are most commonly found in cemeteries or in cities serving as memorials. Most Americans are familiar with the Washington Monument, which may have started the obelisk craze in the United States. Around 1884, when the Washington Monument was being built, Egyptomania was surging through the United States. Egyptomania is described as the fascination with ideas and imagery of ancient Egypt, most likely stemming from Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaign to Egypt, but discoveries from ancient Egypt have repeatedly held our attention. The United States’ fascination with ancient Egypt is strong – just take a look at our money! Obelisks aren’t only seen in the United States, they exist all over the world – Vatican City, Rome, Paris, London, New York, Istanbul – just to name a few locations. Some of these ancient obelisks were stolen during conquests of Egypt while others stand as gifts from their homeland.

Washington Monument in Washington D.C., USA. Courtesy of washington.org.

Regardless of fads, the obelisk has long been regarded as a symbol of stability and permanence, a structure to withstand the ages. Those who designed the Washington Monument wanted to reflect these characteristics and confer ancient wisdom to our young United States.

The Removal Order

DeKalb’s Confederate monument was taken down after Superior Court Judge Clarence Seeliger ordered its removal following a complaint filed by the City of Decatur.

“Based on the Verified Complaint and the evidence and legal argument presented at the hearing, the Court finds that the Confederate obelisk located on real property owned by DeKalb County on the Decatur Square has become a public nuisance, as that term defined in Title 41 of the Official Code of Georgia, and must be abated immediately,” wrote Judge Seeliger. It had been repeatedly defaced since 2015, but until this year, nothing constituted such a strong and urgent cause for removal.

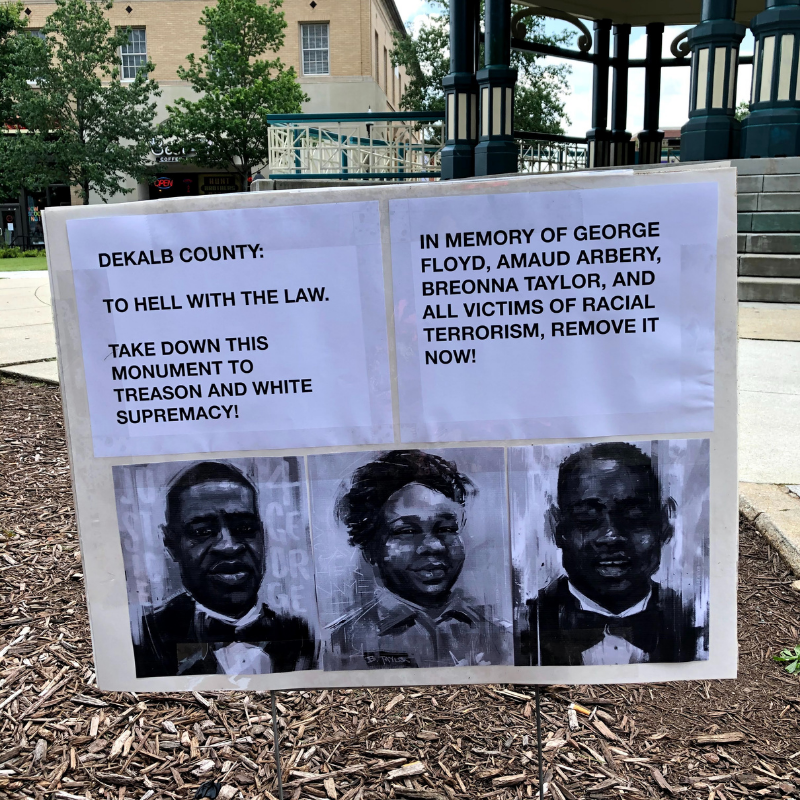

The removal of the monument came after a series of protests sparked by the brutal killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and so many other Black Americans in the months leading up to June 19, 2020. Citizens of Decatur had been advocating to remove the monument since about 2017; current awareness of the monument is due in part to national events. Protests started nationwide after a 2015 massacre of nine Black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, and have been met by counter protests such as the one in Charlottesville, Virginia, when one woman was killed and another 19 injured.

Locally, the Beacon Hill Black Alliance for Human Rights was formed and among its causes, members protested that the Confederate monument should not stand in a prominent public space in Decatur. Initially unable to find legal recourse for moving the monument, the County Commission sought to provide context to the 1908 monument through a new plaque installed in 2019. The marker reads:

“In 1908, this monument was erected at the DeKalb County Courthouse to glorify the “lost cause” of the Confederacy and the Confederate soldiers who fought for it. It was privately funded by the C. A. Evans Camp of Confederate Veterans and the Agnes Lee Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Located in a prominent public space, its presence bolstered white supremacy and faulty history, suggesting that the cause for the Civil War rested on southern honor and states’ rights rhetoric – instead of its real catalyst – African-American slavery. This monument and similar ones also were created to intimidate African-Americans and limit their full participation in the social and political life of their communities. It fostered a culture of segregation by implying that public spaces and public memory belonged to Whites. Since state law prohibited local governments from removing Confederate statue, DeKalb County contextualized this monument in 2019. DeKalb County officials and citizens believe public history can be of service when it challenges us to broaden our sense of boundaries and includes community discussions of the victories and shortcomings of our shared histories.”

The plaque, placed in 2019, provided additional context for the now absent monument.

In Conclusion

Monuments are not history. Many times throughout history, statues and monuments have been commissioned with veiled reasons: in order to push a political agenda, to glorify an ugly part of history, and even to promote the downfall of a race of people. While a monument isn’t always an accurate depiction of history, it is important to learn about who commissioned it and what was happening in the time period to influence its creation.