The General Walker Monument and DeKalb Memorial Park

Learn the history of the General Walker Monument and DeKalb Memorial Park

By Marissa Howard, Programs and Membership Coordinator

Updated July 19, 2024 with added image.

What is the history of this oddly shaped park, squished up against I-20? To begin, imagine it without the highway. The original property covered 82 acres that was bordered by Glenwood Avenue, Clifton Street, Memorial Drive, and Wilkinson Drive. In 1945, plans were made to build the new J. C. Murphy High School – today Alonzo A. Crim Open Campus High School.

DeKalb Memorial Park 2024. Sugar Creek is in the wooded area past the field in the background. Photo by Stephanie Cherry-Farmer

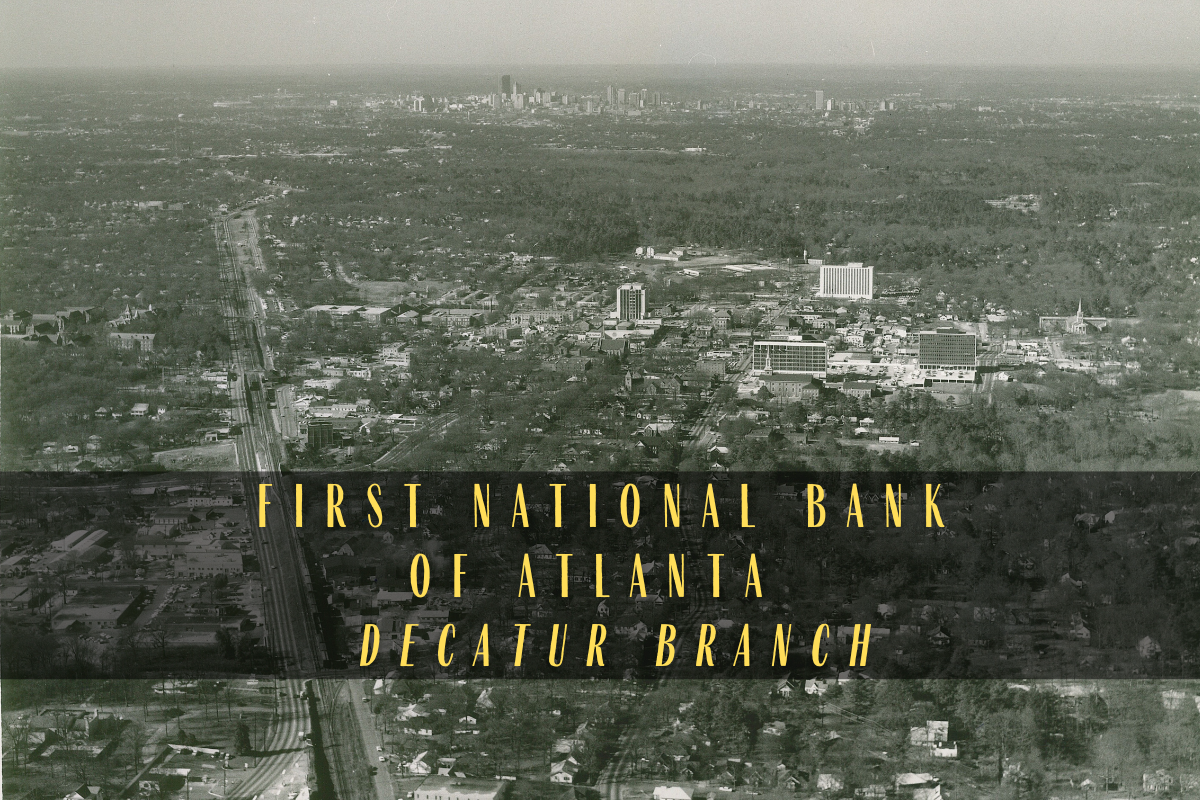

This part of Atlanta, DeKalb County, is well documented for its history during the Civil War. Union and Confederate troops clashed at the intersection of today’s Memorial Drive and Clay Street, in what would be the start of the Battle of Atlanta in July of 1864. Confederate troops led by General Hardee marched 15 miles overnight, splitting into two divisions at today’s intersection of Flat Shoals Road, Bouldercrest Drive, and Brannen Road in the southern corner of East Atlanta. One division continued north along Flat Shoals, passing through today’s East Atlanta Village and engaged with Union troops at Bald Hill (renamed Leggett’s Hill) who had captured the hill the previous night. Only a marker remains of Bald Hill, but a home at the high ground was the site of some of the fiercest fighting of the Battle of Atlanta and the vantage point of the famed Cyclorama painting. The hill was flattened with the construction of I-20 and ramp interchange at Moreland Avenue.

The other Confederate division, led by General Walker, marched north along Fayetteville Road. After they crossed the future I-20, General Walker and General Bates led troops along the marshy creek bed, Sugar Creek Valley.

Sugar Creek Valley can still be seen today, paralleling I-20, still dense and overgrown with kudzu until it reaches Glenwood Avenue and Wilkinson Drive. General Walker was killed by a Union sniper emerging from Terry’s Mill Pond at the edge of the wooded creek bed area close to the present day Shell Gas Station on Glenwood and S. Howard Street. His body was carried to a home near Sylvester Cemetery.

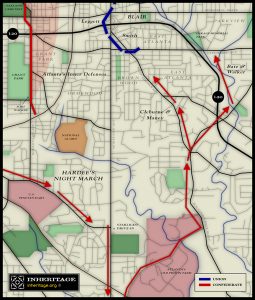

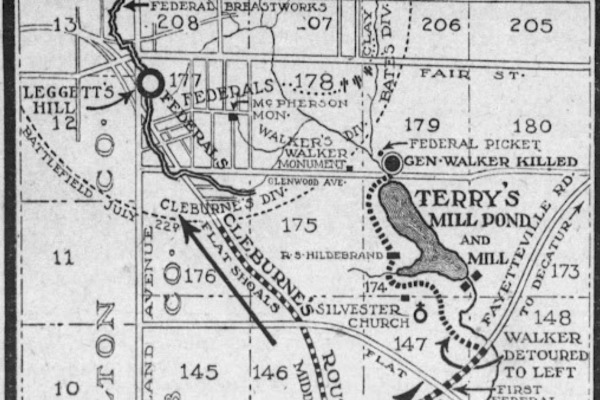

Map of Civil War Troop movement July 1864. Sugar Creek Valley and Terry’s Mill Pond is the upper right corner, labeled Bate & Walker.

Map Source: https://inheritagealmanack.org/battle-of-atlanta-today-history-tour-american-civil-war-maps/

In 1902, Julius Brown, president of the William H. T. Walker Monument Association erected a monument on the location of Walker’s death with the words “KILLED ON THIS SPOT.”

The monument was to be identical and connected “in spirit” to the McPherson Monument (1877), dedicated to Union General McPherson who died the same day less than a mile away from General Walker. Conveniently, the 50 x 70 ft plot of land where Walker was believed to have been killed was donated to the group by Samuel J. Sayler for $1 dollar. The monument was unveiled in 1902: four small cannons surrounding one large cannon. After the unveiling, thousands of people attended the celebrations at Julius Brown’s Country estate “Brownwood.” (Yes, future home of Brownwood Park in East Atlanta). Veterans from both sides were invited to attend in an effort to symbolize peace and solidarity.

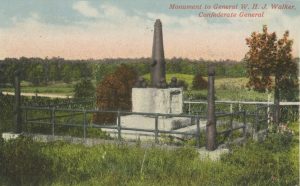

Postcard of Monument to General Walker, original location.

Decades later, in the 1930s, newspaper articles brought renewed focus to the monument. Wilbur G. Kurtz, Sr., leading Atlanta historian and artist, wrote four detailed pages about General Walker in a special feature for the Atlanta Constitution called, Civil War Days in Georgia. He said “It was definitely known where General Walker was killed, but there was no road to the place [at the time]. The approach was over swampy ground of [Sugar Creek], so the association decided to erect the monument as near as they could to the exact spot.”

(Above) Wilbur Kurtz’s Map of the Battle of Atlanta, c. 1935.

(Below) My best estimation of the location of the 1902 monument. Today, this is where Burgess Elementary School stands.

Much has been written, especially over the last few years, about the establishment and creation of historical markers between 1890-1910. In the case of this monument, and many others, it was created and built by a local private group – in this case, a commission. While the National Park Service was established in 1916, there was no such equivalent for national military sites. Spurred by post-WWI memorial efforts in Europe, interest in establishing an official national military parks system peaked in the 1920s. In June 1926, President Calvin Coolidge signed a bill for the “Study and Investigation of Battlefields,” providing the first broad survey of historic sites, from the Revolutionary War to Civil War. From 1926 and continuing through 1932, a survey was conducted by Colonel Howard L. Landers of the Army War College. The Battle of Atlanta and sites all across Atlanta were included, however it was acknowledged that Atlanta’s strong development left few remnants from the war. It was then recommended that $100,000 from the Battlefield Memorial Bill be allocated toward purchasing sites and adding markers for the Battle of Atlanta. About a decade later Civil War fanaticism in Atlanta seemed to reach its pinnacle when Margaret Mitchell published Gone With the Wind (Kurtz was also a historical advisor for the film). The City of Atlanta and DeKalb County began a Historic Marker building campaign, using WPA funds and National Park Service support in hopes of attracting tourists.

Turning back to the battlefield survey in 1930, Col. Howard Landers discovered that General Walker was not killed on the spot of the monument. An in-depth report on the death of General Walker by Kurtz provided further details. In 1935 he wrote, “The present site of the monument would indicate that after General Walker left Fayetteville Road, he kept going westward as if his objective was up toward McPherson Avenue. Such a move was contrary to General Hood’s orders, and General Walker’s record shows he was not only an efficient but an obedient division commander.” The monument clearly needed to be moved .2 miles to the correct and exact location of Walker’s death. In 1935 plans were made by the Atlanta Ladies’ Memorial Association to “rectify the error of the placement of the Walker Monument.” The new plot of land was conveniently available and listed for sale. The land was donated by the Hunnicutt and Ashford estate to the City of Atlanta for the monument and eventually a city park. The new monument was unveiled in 1937.

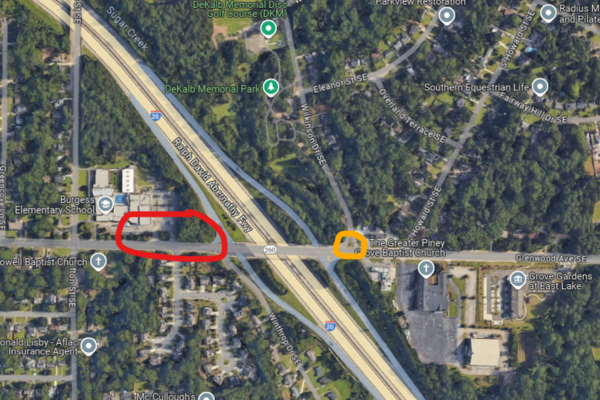

Wilkinson Drive and the Parkview Neighborhood were constructed soon after. The turn lane, which turned the plot into a triangle, was constructed by 1949. Today, this monument still remains on a small triangle plot of land in the middle of an oddly shaped intersection. The cannon marking the entrance to future park land.

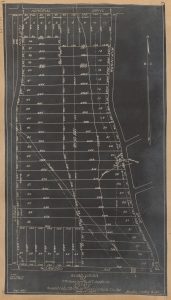

Plat Map of the proposed Subdivision of Hunnicutt and Ashford Estate, 1935. Note the triangle park at the intersection of Wilkinson and Glenwood. DeKalb History Center Plat Map Collection.

Google Maps

After a pause during WWII, the park (future DeKalb Memorial Park) was being considered by Scott Candler, Sr., as the location for an ambitious new project called Soldier Field Stadium at Memorial Park.

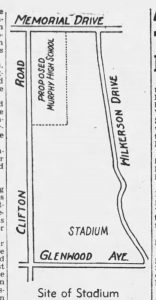

Atlanta Constitution Aug 8, 1946. Note the misspelling of Wilkinson Drive.

In 1946, Candler proposed to build Soldier Field Stadium as a 100,000 seat multi-use facility. He spearheaded this proposal with support from a WWII Memorial Committee, with DeKalb funding the self-liquidating project. When brought to Atlanta City Council for approval in the fall of 1946, his only stipulation was that the City of Atlanta not build a similar type of stadium for 10 years. The project was approved to move forward, but lost traction by October of 1946. By February of 1947, Fulton County Stadium Authority was formed and a site in Northwest Atlanta was chosen for development. However, it was still another 15 years until a dedicated professional stadium would be built. And no, I am not talking about Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium (1964) but rather America Field – in the heart of West DeKalb.