Shermantown, Resilience in Coexistence

Shermantown is one of the oldest Black Communities in DeKalb County. Read the stories of some of it’s longtime residents.

By Monica El-Amin, African American History Coordinator

Prior to the publishing of this article, I was unfamiliar with the existence of Shermantown. I was aware of Stone Mountain due to my proximity to it as a child. I could even tell you about its history with the Ku Klux Klan, and the Confederate memorial’s effect on me at a personal level. However, learning of Shermantown openly confronted my understanding of Stone Mountain’s complex history. Shermantown is unique, as it is between the grooves of the Lost Cause narrative, and the outside world’s aloofness to its presence. This is where Shermantown fills in the gaps of the story commonly overlooked. Black residents of this community established foundations here following the Civil War. The power of memory keeps the community alive as the elders pass down their stories of their livelihood. I used newspaper articles to unveil the stories of Shermantown’s Black community and took a closer look at the memories from residents, which shed light on their awareness of racial disparities and their determination to thrive in the face of adversity.

“A lot of people don’t know what Shermantown is, and I think about that a lot,” says Gloria Brown, a longtime resident and prominent figure of Shermantown.

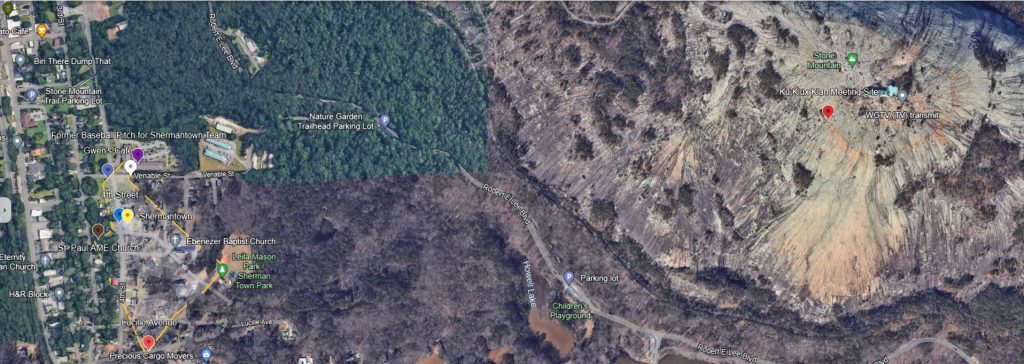

Google Map image of Shermantown landmarks (L) in relation to Stone Mountain (R).

Shermantown is one of the oldest Black communities in DeKalb County. Located at the bottom of the granite mound of Stone Mountain, Shermantown is nestled between the Confederate memorial, and the downtown district. Unless you are actively searching for it, it is easy to overlook the area. The lingering presence of Stone Mountain Park obscures the Black community’s history from view. When you examine the stories of Shermantown, and the people residing in it, the revelations in contrast to Stone Mountain’s history may surprise you.

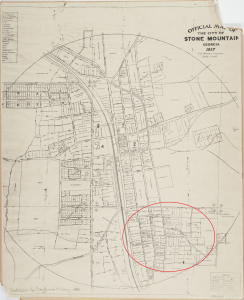

This 1917 map of Stone Mountain shows Shermantown developing around the “Colored Public School” on Still House Road and 4th Street. Area is circled. DeKalb History Center Archives.

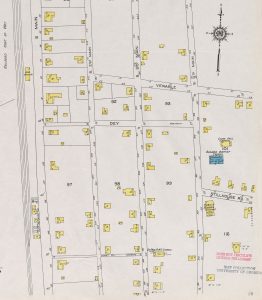

This portion of a 1924 Stone Mountain Sanborn map shows the developing Shermantown in more detail. Map collection of the University of Georgia.

“Mountain of Racial Harmony – Forget Tales of KKK; Shermantown is Peaceful Place”

A 1996 article written by Shawn Evans Mitchell of the Atlanta Constitution, explained that the residents of Shermantown were primarily concerned with ensuring their history was shared with honesty. She reported that the Black community felt strongly about disassociating themselves with the notorious narrative of Stone Mountain; being the Ku Klux’s Klan meeting space for rallies and cross burnings.

Ms. Gloria Brown preferred to define the narrative of her hometown. “Everybody figured we were torn between Black and white because of the KKK,” says Gloria Brown. “It’s not at all like what everybody thinks. We played ball with white children even before integration and never had a problem.” The Shermantown Gloria Brown calls home, was built by the formerly enslaved Black people who named the town after Union General William T. Sherman. “We get an image here as a racial town, and we’ve never had any racial problems. Ms. Brown recalled the vivid memory of her adolescence when she and her family received a visit she would never forget. Recalling a knock at the door of her childhood home, her father answered it. At the threshold of the steps stood a Klansman. He asked her father for a bucket of water as his car had overheated. He immediately helped the Klansman by handing the bucket to him. She stated that her father’s reaction was merely, “You never know who one day might help you.” This memory stuck with her as it was unexpected for something like that to happen, but it ingrained the need for resilience in coexistence.

Fellow resident, Eva Green also recalled nothing but peaceful times in Shermantown. “It was true the KKK came here from all over to have their rallies, and because of that, everyone just labeled this town as racist, and it wasn’t. In fact what I’ve always liked about this community is the family not just between blacks but blacks and whites. That’s why I’m still here.” Green moved to Shermantown in 1951, and she did not experience any racial conflicts whether as a businesswoman or resident. Brown, like Green, cited the community’s “close ties that bind” as a reason for the residents’ consistency in staying in Shermantown. “If you get sick, someone’s here to help you. If my house were to burn tonight, as many white people would come to my rescue as blacks.”

Gloria Brown at Leila Mason Park for Stone Mountain Day in 2017. Photo by Dean Hesse. Credit: Decaturish, supportyourlocalnews.com

“Shermantown: Seniors Called ‘Truest Treasures’”

Laurinda Williams reported on the community’s efforts to preserve its history in 2000 (Atlanta Journal Constitution). “For the children of Shermantown, black history isn’t a school lesson or one month of the year. It is their everyday lives.” Elaine Vaughn lived there for 47 years and recalled the memories of witnessing the shift from Labor Day being a holiday of celebration to the sense of dread when the Ku Klux Klan would enter the vicinity. She described the Ku Klux Klan as riding through the streets of Shermantown screaming racial epithets. Businesses would have to be shut down, as parents instructed their children to turn out the lights, and be quiet. Any sudden movements or sound could be the difference between life, and death.

Mayor Chuck Burris, and Councilman Billy Mitchell pooled money together with the city of Stone Mountain to show appreciation to the senior citizens. The mayor declared this appreciation effort as an annual event in the Shermantown community. He described the seniors of Shermantown as being valuable assets to the Stone Mountain area. One of the honorees at this event was Eugene Benefield who called Shermantown her home for 87 years. “I was honored to receive the award and know that the community thinks much of me. I have seen so many positive changes in Stone Mountain but I am grateful to have lived long enough to see the city have its first black mayor.”

Elaine Vaughn stands at the corner of her street in Shermantown. “I have the best view of the mountain,” she said. Photo by Dean Hesse. Credit: Decaturish, supportyourlocalnews.com

“Shermantown Learned to Coexist”

Gloria Brown was again interviewed in 2001, along with DeKalb County Historian, Walter P. McCurdy, Jr. (by Laurinda Williams). “We’ve got a reputation that doesn’t belong to us,” says Ms. Brown. “Nothing could be further from the truth about blacks and whites not getting along. There was never any racial tension whatsoever. We coexisted peacefully.” Stone Mountain’s reputation was cemented by the gatherings of the Ku Klux Klan. Some Black residents have strong memories of the terror they felt having to witness them riding through the streets, yelling racial epithets. “As a child growing up here, I can tell you that both blacks and whites had the same doctors, just different waiting rooms. We weren’t treated any different,” she continued.

Walter McCurdy (1937 – 2004) was a resident of Stone Mountain. He had memories of familiarity with the Black community through the semi-pro baseball team, the Stone Mountain Hot Rocks. “The white teams wouldn’t choose me because at the time I was all of 90 pounds, so I would play for the black team. And boy, they were good. Sure, we knew there was segregation but we never paid it any mind. We all just had a good time.”

Elaine Vaughn holds a copy of a photograph of the Shermantown community’s semi-pro baseball team, the “Hard Rocks.” Her father Charlie Stewart is 2nd from the right on the first row. Rev. William Woodson Morris, Sr the only living member is at the end of the row to Stewart’s left. The date of the photo is probably 1954. The team was organized in 1946. Photo by Dean Hesse. Credit: Decaturish, supportyourlocalnews.com

“Blacks Found a Home in Baseball as Shermantown dealt with Klan”

More information on baseball in Shermantown was revealed in a 2005 Atlanta Constitution article, by Karen Hill, featuring Reverend William Woodson Morris, and Joseph “Big Bear” Smith. During the era of segregation, the historically Black Shermantown became the central point for Black athletes in the Negro Leagues, and business sponsored teams. Hundreds of spectators would come to support them. Some people would purposely skip the Atlanta Braves games to see the negro teams play instead. Reverend William W. Morris, played for the Stone Mountain Eagles, a sandlot team. He still lives in the home he was born in, adjacent to the baseball field he played in. Joseph “Big Bear” Smith played for the Scripto Black Cats, a team sponsored by the Atlanta Scripto Pen and Pencil Company. The friends spent time together reminiscing about players and games. Neither of the men can particularly pinpoint why the communal excitement of baseball occurred within their community but they happily recall their own excitement. “If it was May or June, every little boy would be in a field somewhere playing ball,” Smith reported. “We could play till 4:30, when the guys working on the mountain would come from work and have a big ball game until game night. It didn’t make no difference if it was hot.”

The Black community of Shermantown will inform outsiders that the Venable family protected them from Klan violence, sponsored community barbecues, as well as allowed black families to fish, saw timber, and live rent-free on the Venable land. The Venable family even donated granite to build the historic Bethsaida Church. Sam Venable, the original owner of Stone Mountain, would invite the Klan atop the mountain in 1915; his nephew, James Venable, would grow up to become the imperial wizard of the National Knights of the Ku Klux Klan (formed in 1963). “We had no problems with no people [in the Klan],” said Reverend Morris. “We never had any problems with lynchings. It was just political stuff. James Venable was just making money off their ignorance.” This is where the inner workings of Shermantown become confusing to those who do not understand the dynamic. Their resilience in coexistence came in the form of knowing who the devils among them were. It became an illogical form of survival and sustenance. By day they worked with the white employers and employees who would gather at night as Klan members at the top of the mountain. This became commonplace for them as James Venable was the lawyer for the Black community.

Rev. William Woodson Morris, Sr. sits with a portrait of his late wife of over 50 years, Ms. Lucille B. Morris in the living room of the house where he was born in 1928 and still lives today in Stone Mountain’s Shermantown community. Photo by Dean Hesse. Credit: Decaturish, supportyourlocalnews.com

“Playwright Sheds Light on ‘Overlooked’ History: Works Depicts Blacks’ Plight in Era of Segregation”

These interwoven stories made headlines in 2005 in the Atlanta Constitution, when playwright Calvin Ramsey staged a reading of his controversial play entitled: “Shermantown: Baseball, Apple Pie, and the Klan.” The play examined the intersections of white and black dynamics in the city of Stone Mountain, and the black community of Shermantown. When Ramsey was going to stage the play, he found himself entangled in the controversy due to its nature. In a sit-down interview with Jeffrey Scott, he took the time to discuss the overlooked history of it. When asked about the controversy of the play incorporating coarse language from the Klan leader as being too divisive, and how the black community navigated it, he had a poignant response. “Black audiences have been very supportive. Both readings of “Shermantown” were sold out.” He continued by stating: “One interesting thing has occurred. I’ve gotten a lot of feedback from middle and upper-class blacks who have said to me, ‘Keep it up!’ I thought, ‘Keep what up?’” Eventually, Calvin Ramsey theorized that the Black people who resented segregation the most, were the Black professionals who received educations and ran businesses. He mentions their resentment carried over from the Jim Crow era into the present.

From his perspective, Ramsey understood that some members of the public would be upset. However, when looking at the community of Shermantown, the livelihoods the black population faced were their reality. Segregation is a controversial topic within the Black community. However, Shermantown was in an interesting juxtaposition compared to other communities. Residents were very aware of the racism that existed but they had to work within the confines of it. Segregation did not stop them from maintaining their communities. The Venable Family was an integral part of Stone Mountain, and Shermantown. Black people in the community thrived because they used the tactic of resilience in coexistence.

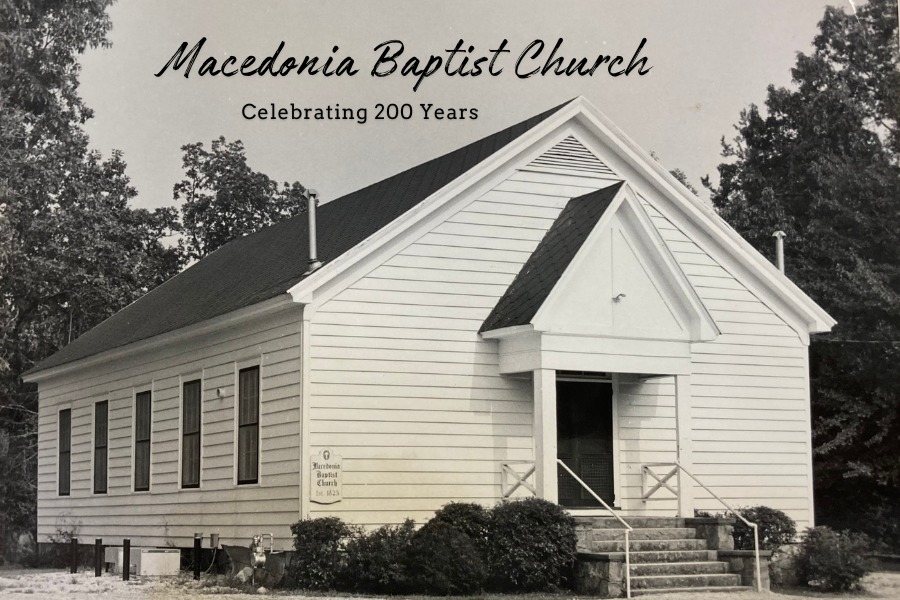

Bethsaida Baptist Church on Fourth Street, founded in 1868. Photo by Dean Hesse.

Shermantown is a unique Black community in Stone Mountain. Each of the memories and stories told by residents leave an impactful legacy of the neighborhood. Though the community is in danger of being forgotten, the remaining black residents are taking control of their narrative. Contrary to the idea that Stone Mountain’s communities were divided by racism, the Black residents of Shermantown are hoping to prove that they are not to be sympathized with. They look at their situation with the understanding that it was the norm. As time continues to pass, they have remained steadfast in their resilience through coexistence.

Learn more about Shermantown Here: DeKalb History Center YouTube Channel

This article reflects the opinions and perspectives of Shermantown residents from 1996-2005. To read further about current thoughts and opinions from 2021, we recommend the Decaturish article, ‘There’s a lot of love in the community of Shermantown’ linked here:Decaturish Article