Post War DeKalb County, a Shiny Industrial Future

Post War DeKalb, a Shiny Industrial Future

DeKalb County experienced massive growth in the years following WWII. We investigated the postwar period from 1945 to 1955. This subject will be split into three separate posts.

By Valerie Biggerstaff, DHC Board Member and Marissa Howard, Programs and Membership Coordinator

At the turn of the 20th century, DeKalb County remained rural with fewer than 10,000 residents. However, by mid-century, DeKalb outgrew its neighboring counties in population and wealth. Once used for agriculture, open land became home to industry, homes, and businesses. In 1958, the headline, “Peachtree Leads New South to Shiny Industrial Future,” was splashed across a full page of the Atlanta Constitution. Peachtree Industrial Boulevard, built only 13 years prior, was now a tangible symbol of progress and the New New South.

By the 1970 census, DeKalb was the 33rd wealthiest county (by median income) in the United States and the only county in the South represented in the top 50. (1)

Research and writings on Postwar DeKalb are not new. We hope the research in the following posts brings a fresh perspective and new archival material to this topic.

Part 1- How Did We Get Here?

Scott Candler, Sr. – Mr. DeKalb

To discuss the growth of DeKalb County, we must start with why it all happened. Known to many as Mr. DeKalb, Scott Candler served as mayor of Decatur (1922 – 1939) before he became the county’s first and sole commissioner (1939 – 1955). Because his position meant that he was the county government with much power concentrated in his hands, some referred to him as a benevolent dictator. At the time, Georgia law allowed one-person county commissions “with exclusive control over all phases of county operations.” This type of government was not uncommon.

Candler’s impact on the county began before WWII, when he stretched WPA (Works Project Administration) funds to maximum benefit. He built new roads, schools, libraries, and most critically – a new water system (1940). Miles of roads were constructed and paved, and DeKalb-Peachtree Airport was built. Candler was dubbed the “master architect of DeKalb’s industrial growth” and is credited with bringing more than 69 industries to the county.

During his 16-year tenure, DeKalb County went from a rural dairying county to the wealthiest county in the South. The county’s population doubled, and new schools, subdivisions, and shopping centers sprang up at every major intersection.

Among his lesser-known but important initiatives was bringing public parks to the country. He developed a $100,000 park in Panthersville as the DeKalb Agricultural Fairgrounds (1938) and Memorial Park (1946), which he envisioned as the future home of Soldier Field Stadium, with an estimated cost of $2,000,000. Candler never saw a DeKalb stadium built in his lifetime, but remnants of that singular vision are today’s DeKalb Memorial Park.

Headquarters for Scott Candler’s re-election campaign as DeKalb County Commissioner, ca. 1950, located at 320 E. Howard Street. Gaines Brewster Collection.

Dairy and Agriculture

In the early decades of the twentieth century, DeKalb County was still home to thousands of farms; some planting cash crops such as cotton and others planting only the crops that they needed to feed their families. In the ten years that followed the destructive boll weevil (1915-1925), Georgia cotton production dropped by half, and many farmers gave up agriculture altogether and moved to the city to find jobs in industry. Other farmers adapted to the changing tide and took up dairying.

In the 1930s, DeKalb County boasted “more cows than any county outside Wisconsin,” with almost 240 independent dairies operating before WWII. (2) Proximity to the large and growing Atlanta market, coupled with an abundance of cheap land and lack of strict regulation (before pasteurization was mandated in 1943), made dairy farming a popular survival strategy, especially for those left destitute by the boll weevil. In 1936, “there wasn’t much else we could do,” according to Henry Milton Sheppard of the bygone Sheppard Brothers Dairy in Stone Mountain. (3)

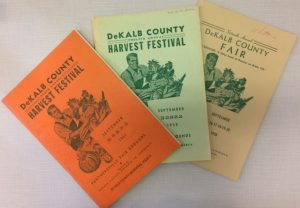

The DeKalb Chamber of Commerce and Agriculture was founded in 1938. As the name suggests, agriculture was a fundamental aspect of DeKalb’s economy. The Harvest Festival, started by the Chamber in 1938, was hosted on the DeKalb Agricultural Fairgrounds in Panthersville. Originally a one-day event, by 1945 it had grown to a five-day affair that attracted hundreds of thousands of visitors. This festival allowed the community to enjoy themselves while also providing exhibitions of agriculture and livestock from the area. Furthermore, the festival served as an advertisement for the county, enticing visitors from all over the state to get a look at DeKalb.

DeKalb County Harvest Festival Programs, DeKalb History Center Archives.

Dairy farms blanketed Doraville and Chamblee. The intersection of Buford Highway and Shallowford Road was once home to the I. O. Morton Dairy. The Morton Dairy sat on 62 ½ acres with a large dairy barn built of stone, a milk house, large feed room, and three family homes. In 1949, the farm was up for auction, with its location advertised as near Lawson General Hospital and the General Motors plant. (5) The J. H. Maloney Dairy was on the future site of the General Motors plant. John Harwell (Bud) Maloney delivered milk to Doraville and families in nearby communities. (4)

In East Lake, on Glenwood near Terry Mill Road, was the East Lake Farms and Dairy, owned by Robert Usher Kitchens, Sr. Kitchens began selling off his 30-acre property in 1946 and passed away the following year. His sons, who had returned from serving in WWII, moved on to other professions, including dentistry and construction. That farm is now the neighborhood off Terry Mill Road, a quintessentially post-war Ranch House neighborhood. DeKalb was changing; around 1949, “Agriculture” was dropped from the name of the DeKalb Chamber of Commerce, unofficially marking the county’s change from agriculture to industry and commerce.

Robert Kitchens, Sr., & Elon Kitchens in front of their house at 1955 Glenwood Ave. Today, this property is the Grove Gardens at East Lake Apartments—photo courtesy of David Kitchens.

Further south in DeKalb, near Bouldercrest Drive, dairy farmers Samuel E. Smith and Hiram Stubbs founded Atlanta Dairies Cooperative, which benefited the owners of small family dairies whose sons and younger employees left to serve in the armed forces during World War II. In addition to labor, materials for pasteurizations were in short supply. Atlanta Dairies built a large plant at 777 Memorial Drive to process milk from 43 local farms. This consolidation started the decline of our local dairy industry.

Atlanta Dairies operated until 1993, when it was sold to Parmalat, which operated until 2008. The Streamline Moderne building was renovated into a mixed-use facility. In 2018, Atlanta Dairies Cooperative re-emerged as a dairy cooperative. Photo by Garey Gomez for Rough Draft Atlanta.

Nearly every dairy farm in DeKalb had similar stories to these examples. World War II had a profound effect on every aspect of dairy life. What came after the war was a completely different DeKalb than before.

The last known working farm in DeKalb was Vaughters Farm in the Arabia Mountain National Heritage Area. The barn and land remain untouched and protected. “If Mr. Vaughters had not been willing to do this, it would have become a subdivision, no question about it.” Kelly Jordan, President Arabia Mountain Alliance in 2002.

Vaughters Farm, Vivian Price Collection, DeKalb History Center Archives.

In our next installment, we will examine the boom economy in cities across DeKalb.

Sources:

(1) “50 Richest Counties Are In Suburbs,” New York Times, September 19, 1972.

(2) “Single-Family Residential Development: DeKalb County, Georgia 1945-1970,” Georgia State University Heritage Preservation Graduate Studies Program, 2010, p. 22

(3) “Where the kids met the cow,” Atlanta Journal Constitution, February 9, 1996.

(4) “Dairy squeezed out: Urban sprawl puts an end to Atlanta’s last milk producing farm,” Atlanta Journal Constitution, September 16 1995.