Pocket Portraits and Precocious Evangelists

This article was originally published in the DHC’s Spring 2010 Newsletter.

Portraits of those we study.

I want to ask you to do something. Imagine yourself sitting in a room, perhaps on the floor, in front of a box. We’ll get to the box in a moment. The room will be small and dimly lit. It will have a musty smell not unlike a closet in your grandparents’ home. It will be comforting, I promise. Put your hands on the box; trace your fingers along the edge of the lid. Its rough surface is almost like cardboard at this point, but that is only an illusion. Years of opening and closing, emptying and searching have nicked and scuffed its once clean lines into soft manila curves. Open the box. Pictures, diaries, the smell of dust and mildewed paper will flood the room. Sifting through these images of people you could have known, who share a bloodline and a history, holding their things – a mirror, a hand brush – in that moment you are struck with the enormity and complexity of a history you have never known before but always felt.

Maybe this scene isn’t exactly what you experience when filtering through boxes of family knick-knacks, but I do. Ever since I was little I can recall reveling in the prospect of going to a grandparent or extended, elderly family’s home. Not because of sweets, not the hugs or the kisses or games they would play with me, but because of their closets, bookcases and the catacombs under their beds. It was a wonderland. In these nooks were tucked traces of their past, of lives I could never imagine them living, of their relatives. They all had stories, they all loved people, were a part of history I was learning in school, and were a part of me. As a child I craved that kind of connection to the past, to a time when things seemed constantly changing and imminent. When things felt as if they were moving towards something. I still do.

When I moved to DeKalb County in August of 2008 as a first-year at Agnes Scott College I knew what most high school graduates would know about the metro Atlanta area: Sherman. Fires. Carpet Baggers. Rail Roads. Atlanta and Decatur seemed like these towns with a history and life that I knew, but that wasn’t mine. Ever since grade school we had learned of the calamites of American Culture and of course Atlanta was always mentioned. But it wasn’t personal. It wasn’t people. It was war, disease and things that a child is not eager to relate to. So I didn’t. It seemed like one more unit of study I had to trudge through on my way to the end of school. However as the next two years passed by and I began to outgrow the myopic mindset that is so intrinsically linked to adolescence, I felt that pull again. That pull of stories I knew were living and breathing in the buildings I walked every day.

You may or may not be familiar with the host of ghost stories that inundate the Agnes Scott Folklore, but that is where it started. The white ghost, the red ghost and more: students past and residents of Decatur before Agnes Scott was even a thought in General George Washington Scott’s dizziest daydreams. It sounds cliché, but it is true: it all clicked. I was walking in on this town, on this institution, calling it my home and making it mine without any real investment in the people who had spent their entire lives here, being a part of a world I can only attempt to understand. I felt like a heretic.

Working at the History Center has opened up the world of DeKalb County to me. Open a box, any box, and there are ciphers and codes. Letters, notes, memos, class photos, candid photos. They all compile the lives of people who could very well have sat where I sit, walked where I walk, slept where I sleep. They weren’t the distant and impersonal class photos, unnamed faces in a textbook. They expressly belong to the history of DeKalb County, and that is one interesting past to say the least. In school it seems that any part of history that a student does not understand or cannot connect with is assumed to be the result of the pasts’ ignorance, to their archaic nature. Eccentricity is avoided, deemed freakish, when in fact it is those eccentrics that have pushed DeKalb County into what it is today; they made it possible by living. These traces can start innocently enough. They can be subtle.

Miss Sallie Bagwell’s pocket portrait

A collection of portraits. Nothing special, right? But what about when the portraits are thumb-sized, not unlike a yearbook photo you may carry of a loved one in your wallet. But look a little closer. One picture, “Sallie Bagwell” sits ready to be looked at. Her likeness is no larger than a bag of tea. The photo is losing its color with time and shows the scratches of daily handling. Her stare is straightforward, but not distant like so many other portraits from the latter half of the nineteenth century. Her mouth is pursed, almost as if there was something she wanted to say before the shot was taken. She is breathtakingly beautiful. Holding her in time is a tiny frame. A frame. How likely would you be to frame such a small photo? Someone put the thought and money to have Ms. Bagwell framed, when her portrait today would likely find a grave in the bottom of some junk pile next to socks and newspapers.

Can’t you just imagine someone carrying around her picture, fingers going over the frames edges whenever the heart panged? Sallie lived a life before and after this picture was taken. Was she happy? Did she go to school? She experienced the world in some capacity, and was here when DeKalb County was just blooming. Her picture exists, her life has proof. It is up to us to give her life and those like her meaning by remembering her not as an abstract example of a Victorian woman, but instead as a woman from Georgia who someone loved enough to take their picture. It’s definitely nice to think of it that way, anyways.

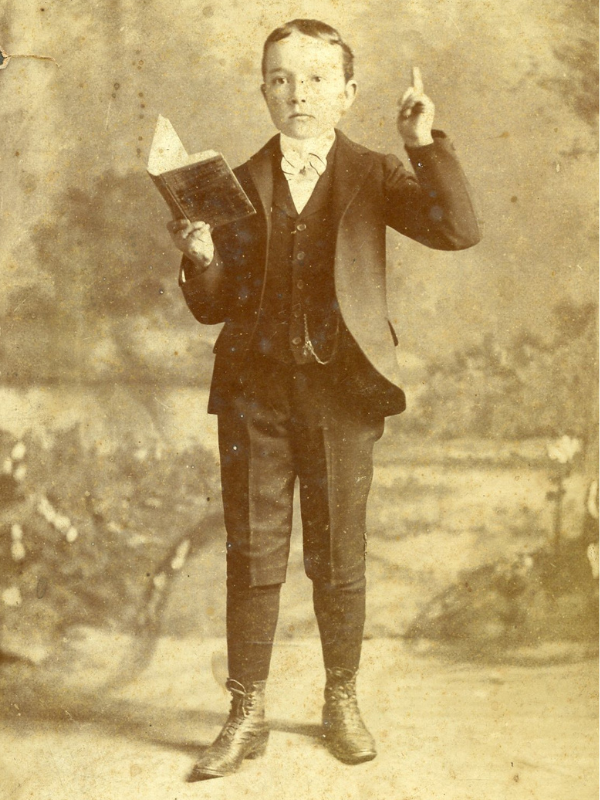

Next photo: Revered Metz Joiyner. We have all seen many pictures of men of religious standing, probably enough to last us a lifetime. But Joiyner is different. He was a nine-year-old preacher. What were you doing when you were nine? He is standing in the picture, Bible poised in one hand whilst the other raises a finger towards Heaven, enumerating some point to his flock, no doubt. He is dressed in a fine suit, bow tie and watch completing the look. He has a look of complete conviction on his young face. The idea of a community placing so much faith in a child is mesmerizing. For a child to have that much faith in God, enough to preach about, is equally mesmerizing. Under what circumstances did this child come into such a position of power? It is next to impossible that he lived among complacent people who would photograph a child pretending to be a preacher. He must have been truly extraordinary, an eccentric to say the least, to manage becoming a Reverend by nine. He also was likely an insufferable child as precocious children have the tendency of being. Little facts like this, little eccentricities, they make the characters real. These photos obviously raise a lot more questions than answers they can give, but is our world ever without questions? Can you imagine a world without a past worth questioning?

Reverend Joiyner, nine years old, poses with his bible

While these two examples may not seem of paramount importance to the grand scheme of history and its effect today, they are just one piece of the puzzle. So much of our present understanding of history stems from big-picture concepts: war, depression, and discovery. But what about the people that lived every single day in the vague time periods we study? The events in DeKalb County’s history happened because real life people made them happen, they talked about issues and moved through their troubles, creating the world we live in today. How can anyone possibly think that the future can greet us as gently as possible if we do not have a concept of how it felt to those like us in the past? Not everyone in the past was an activist, politician or figurehead. Most weren’t. It is not so different today. It is true we must learn from the past; study the bullet points and chapter headings. But by closely reading the story of the past we can begin to appreciate its culture, which is inherently ours. We can map our lives by studying theirs, understand why our cities behave the way they do by looking at their past.

Since 1947, how many stories have been saved, stored and are now waiting for hungry eyes, waiting to be told? It is easy enough to go through your day to day as it is. Life is hectic and complicated and does not often lend itself to the luxury of studying history. But if you take one moment out of your walk through Decatur’s Square, on a drive to Stone Mountain or any other reach of DeKalb County it can be fulfilling to just imagine what happened exactly where you stand 100, fifty, even just fifteen years ago. The world is in such a constant state of flux that things that seem commonplace today will be obsolete tomorrow. Just imagining what could have been happening where you are can be an adventure in historical romanticism and significance. Try and hold on to some of the things that are so intoxicating about your favorite parts of the past. I bet you can find a trace of them feet away from your door. It is all around us.

Since 1947, how many stories have been saved, stored and are now waiting for hungry eyes, waiting to be told? It is easy enough to go through your day to day as it is. Life is hectic and complicated and does not often lend itself to the luxury of studying history. But if you take one moment out of your walk through Decatur’s Square, on a drive to Stone Mountain or any other reach of DeKalb County it can be fulfilling to just imagine what happened exactly where you stand 100, fifty, even just fifteen years ago. The world is in such a constant state of flux that things that seem commonplace today will be obsolete tomorrow. Just imagining what could have been happening where you are can be an adventure in historical romanticism and significance. Try and hold on to some of the things that are so intoxicating about your favorite parts of the past. I bet you can find a trace of them feet away from your door. It is all around us.

I will go so far as to say that one would not take on a new endeavor without weighing things that have happened in their lives, experiences that may lend themselves to a new venture or deter it. The same should be said for living today: you cannot go anywhere until you know where you have been, who you could have been.

Christen Thompson, originally of Chapel Hill, NC, is a Creative Writing major at Agnes Scott College. She has worked as a Joyce Cohrs Archival Intern at the DeKalb History Center since February.

(This description of the author is from Spring 2010.)