Decatur’s Second Empire “Marble House”

The Marble House, Decatur’s only example of Second Empire Architecture, was built in 1880. Learn its fascinating history, which reflects changes to Decatur’s urban core.

By Melissa Carlson, Executive Director

I had strolled by Decatur’s only Second Empire house numerous times, and never noticed that something was “off” about the house. Suddenly, a closer look was in order and I decided to walk all around it. What was the house missing from the street? It was so obvious that I was a little embarrassed. What was missing was the front façade; I had only been looking at the side of this unique house for all these years. I needed to know, what was its story?

Most small Georgia towns only have one or two homes built in this architectural style (1870s – 1880s), which was more popular in larger or coastal cities. Since they are uncommon, I was not surprised to find this house had its own subject file in our DHC archives. The most distinctive feature of a Second Empire house is the mansard roof, which is actually the top floor. The walls of the top floor are curved or sloped, generally covered with slate tiles (as is the actual roof), and punctuated by dormer windows. According to Sanborn Maps (see end of article), this house had a wood shingle roof, which is unusual for this style. These homes usually have a tower, and two early photos show this feature before its pyramidal roof was removed. Now what remains is an out-of-context bay over the porch roof.

- Augusta’s Zachariah Daniel House, ca. 1875, from Old Georgia Homes Blog. Augusta was much more populous than Decatur in this time period. This house provides an example of Second Empire with a slate roof and its original one-story wood porch.

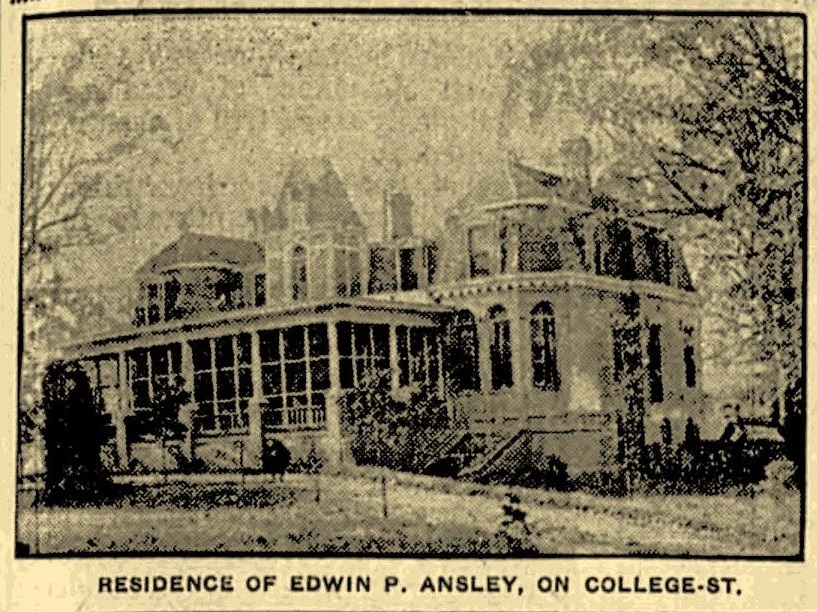

- “Atlanta Georgian and News,” Nov. 11, 1908. I suspect this is not the original porch, but instead a change made between 1890 and 1908. Note the roof on the central tower.

It was called the Marble House by locals because it used a popular technique where the exterior brick was covered with stucco and then scored to appear like blocks of stone. This house was built with load bearing brick walls that range from 18” to 24” thick. Quoins were also frequently used on this style, appearing on the right angle corners of the main house and emphasizing the “stone” construction. Arched windows and doors can be characteristic for this style and are seen on the Marble House. The two-over-two windows have semicircular glass transoms. The window arches are supported by plain engaged columns, while the main entry has a weighty fluted door surround topped by a keystone. It has two sets of one-over-one triple windows that reach to the floor. Plain window hoods adorn the windows without transoms.

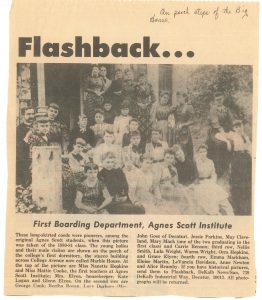

The symmetrically balanced façade was missing its large one-story wood front porch when the house was restored in 1985. Historic photos show two different versions, and the house was restored with porch columns similar to those seen in the Agnes Scott picture. The 1985 restoration underplayed the size and decorative nature of the original front porch – but there were no remaining details to copy. I would have expected more substantial columns and some decorative gingerbread trim. The current owner has a photo from the 1920s that shows a large screened porch with plain Doric columns set on plinths. A later photo shows a plain remodeled porch in the background.

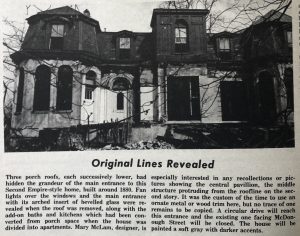

- An undated clipping from the DeKalb News Sun. From Bruce Hagen.

- The Marble House in the 1920s. Note the scalloped gingerbread above the first floor, the tower roof, and the screened porch with Doric columns. From Bruce Hagen.

- Gaines family photo showing a later change to the front porch. The Doric columns have been replaced by plain square posts and the screen is gone. From Bruce Hagen.

The front corner rooms are anchored with bay windows. On the interior, the southernmost room is octagonal, and this could be original as its trim and moldings appear unaltered. However, it creates an unusual shape to the room behind it, with a window partly tucked behind the wall. The northernmost room is not octagonal but could have been when originally built. Both bays have doors onto the front porch that likely replaced windows when the house was divided into apartments. The house retains scalloped gingerbread in the eaves of the dormers but it is missing from the cornice as seen in historic photos.

The front of the Marble House cannot been seen very well from N. McDonough Street and it is also obscured by newer development.

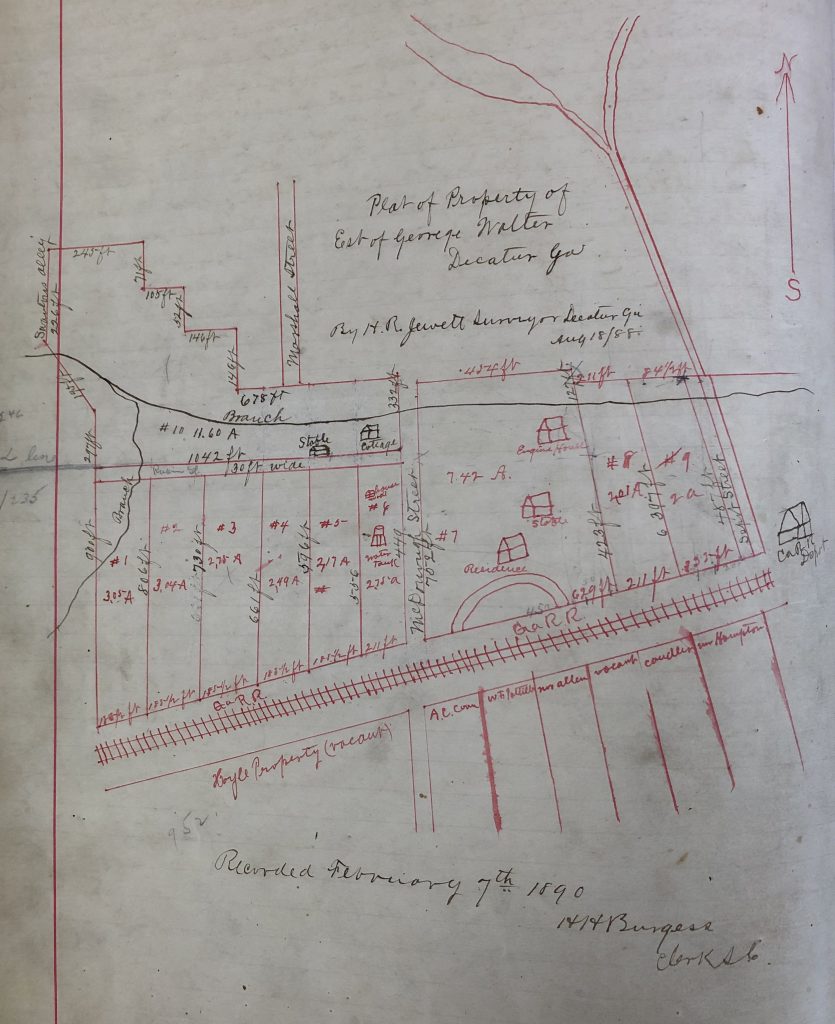

This spacious home was built in 1880 by George Walter of Savannah, Georgia, and originally had a huge tract of land. He was a wealthy cotton broker who built this house in Decatur to escape the low country’s heat and mosquito-borne diseases, especially yellow fever. Since it was a summer home, its architectural details are actually less extravagant than you would see on an urban example of a Second Empire house. The Savannah Morning News reported in September of 1880 that “Mr. & Mrs. George Walter have named their beautiful and elegant summer residence in Decatur, ‘Charlton,’ in honor of Dr. T. U. P. Charlton of Savannah, their family physician.” The Walter estate, which was very convenient to the railroad depot, was bounded by College Avenue/Howard Street, Church Street, a line that ran behind what’s now East Maple Street, and roughly behind what now makes up Decatur High School’s property. It straddled North McDonough Street. In addition to the house, the property had two stables, an engine house, a water tower, a creek, and two cottages that were probably for people who worked on the estate. The water tank was reported to hold 8,000 gallons for a “fine herd of Jersey cattle and other stock . . . which will afford a constant supply of pure water.” There were also reports that Walter erected a white fence all around the property, which was “unlike anything in Decatur.”

This hand-drawn plat, while not quite to scale, shows the Walter estate at the time of his death. DeKalb County Deed Book NN-214.

Mr. Walter died in 1888. As his estate was being settled, it was reported that he owned forty acres in Decatur. The property was soon sold to Frank J. Ansley, and the Marble House was briefly used by Agnes Scott College as a dining hall and student dormitory (1890 – 1891). Frank sold slightly less than half of the land, including the house, to his brother, Edwin P. Ansley. Edwin later left this mansion to move into Ansley Park in Atlanta, which he developed. When he began marketing this estate for sale in 1909, he proposed subdividing the remaining Marble House parcel into 15 lots – one of which preserved the integrity of the Marble House with its front unobstructed and facing the railroad tracks. It did not sell this way. Instead, the entire block was split in two (creating an alley from College Street to East Maple), with Edwin keeping the western side. In 1913, he sold his three remaining lots, with the house, to J. W. Glass. Since all of the lots on either side were oriented to face North McDonough, the Marble House no longer “fronted” the railroad tracks. Eventually five small brick clad bungalows were built on the two lots between the Marble House and College Avenue.

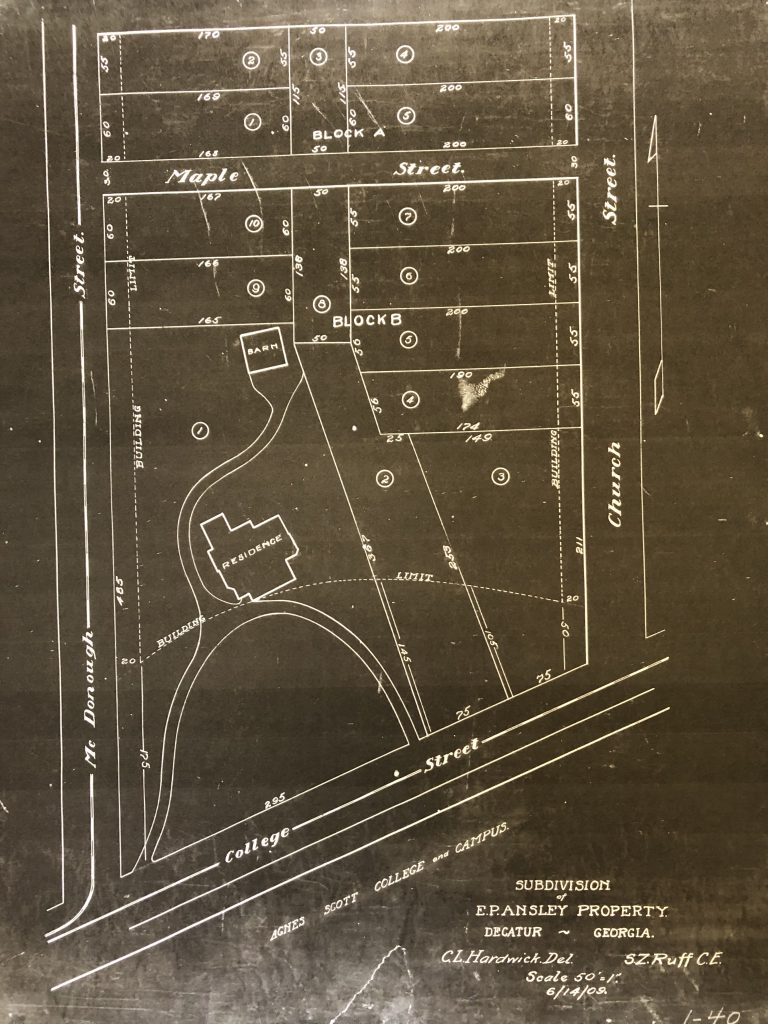

This was how Edwin Ansley proposed dividing the remaining land around the Marble House when he was ready to move. DeKalb County Plat Book 1-40.

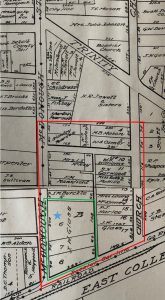

This plat, created in 1911, more accurately reflects how the property was divided at that time. DeKalb County Plat Book 1-37.

These boundaries are sketched over DeKalb County Atlas, Maynard-Carter-Simmons, 1915. The red outline is what Edwin Ansley owned when he subdivided the land in 1909. The green indicates the three lots purchased by J. W. Glass in 1913. The star shows the Marble House lot. DHC Archives.

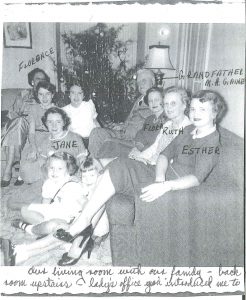

The house and two vacant lots were purchased by John A. Gaines in 1924. He was also “a prominent real estate man.” The Gaines family would retain ownership of the Marble House and one brick bungalow until 1973. The Marble House was used as a residence by J. A. Gaines’ son, Milton A. Gaines, and his four daughters: Ruth, Florence, Flora, and Esther. All of the daughters later married. The 1928-29 City Directory lists these residents at 213 N. McDonough: Mrs. Blanche Mauldin (widow), Milton A. Gaines (householder, carpenter), Flora Gaines (student), Florence Gaines, and Ruth Gaines (stenographer). The Marble House was transferred to his daughters and their heirs in 1941.

Milton A. Gaines with his daughters and grandchildren. They are in one of the upstairs rooms which they used as a living room. This undated copy is from Bruce Hagen.

The first new bungalow was built in “front” of the Marble House around 1925. This was likely when a large entry door was added on the side of the house to create a new front door onto McDonough Street. This would have resulted in some substantial interior changes to the house because the new door was placed where an interior wall and two fireplaces had been. The McDonough front door is seen in two 1960s photos from the Gaines family but has since been removed. By 1943, the house (now 119 N. McDonough Street) had been divided into seven apartments with Ruth Gaines Snellings’ family occupying one, and her dad, Milton Gaines, in another. It appears that the other five apartments were rented to people outside the family. The Gaines daughters sold the house in 1973; and until 1985, the house was rented out as six separate apartments, including one to Ruth Gaines Snellings.

- This 1960s photo from the Gaines family shows the door added to the N. McDonough side of the Marble House. From Bruce Hagen.

- The same view of the Marble House in 2021.

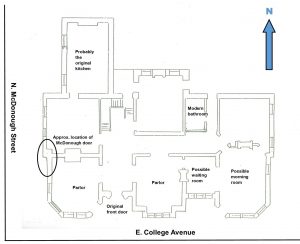

Many locals “lost sight” of the 6,000+ square foot Marble House by the 1980s because it was hidden by big trees and overgrown shrubbery. Over the years and during its use as an apartment building, some of its original features were lost, including two fireplace mantels and its grand staircase. Porches were removed or enclosed, and small, utilitarian kitchens and bathrooms were added. In 1985, its new owners created the Marble House Corporation to restore it, and hired Mary McClam Designs to lead the restoration. She had recently completed the restoration of the High House (309 Sycamore St.). For this prominent historic preservation project, she returned what had become an apartment house to its “single family” layout, with the intention that it would become offices. The Marble House was restored to a total of 14 large rooms plus spacious hallways; the one-story room at the rear of the house was probably the original kitchen. The original front door was uncovered in place during demolition, but it was almost immediately stolen from the site.

Decatur-DeKalb News/Era, Apr. 18, 1985.

Mary sought assistance from the DeKalb History Center when she began the restoration. She was looking for information about its former appearance or occupants. Unfortunately, she did not donate any of her materials to our archives after the project concluded nor after her retirement. Now, 36 years later, it would be useful to have a description of the house’s condition when she started work (through photos, floor plans, or saved materials), and what guided her restoration decisions. Which are the remaining fireplace mantels and which were presumably salvaged from another old house? Could she document when the McDonough front door was added? Did she find any old photos?

I contacted the current owner, attorney Bruce Hagen (Hagen Rosskopf, Attorneys at Law), to ask if I could see inside. To my delight, he not only showed me around, but shared archival materials he had received from the Gaines family – materials not available to Mary McClam during her renovations. He has been the owner since 2003 and has continued its preservation as a labor of love. The house is beautiful and well maintained. Early in the Covid-19 pandemic, he refinished the original oak floors, which are in great shape. Prior to that, he completed extensive foundation repair which was required due to the masonry construction. The foundation bricks do not appear to have been fire glazed and time and water eroded the stucco coat that held them together. Old house aficionados know that some of the most important – and expensive – repairs go unseen by visitors. Bruce’s work to shore up the foundation required a new structural I-beam and cross ties in the basement.

Despite the changes, a visitor today crosses the threshold and steps back in time. The front door delivers you to a large hallway that faces the main staircase, and which was presumably grander when originally built. There are two parlors on either side and 12 foot ceilings throughout the first floor. Both parlors feature large paired four-paneled doors with arched top panels that can be closed to create more intimate spaces or opened to allow for a larger party. All rooms are finished with large baseboards and window and door casings. One room has an elaborate picture mold and another has a sculpturally curved crown molding made of plaster. One set of triple windows creates a small bay on the inside of a parlor with an arch springing from elaborate wood pilasters. These same pilasters are used again to frame the entrance into the southwestern parlor, which may have served as a morning room. In the Victorian period, a morning room was typically used by the lady of the house to prepare for the day and also to receive her visitors. This is a speculative use but one that is made feasible because the room has eastern exposure and the small room next to it could have served as her waiting room. One can imagine other uses for the downstairs rooms – there would have been a dining room, perhaps a breakfast room, and possibly a library or study for the men. There would have been a gender separation for some of the public rooms during its early history.

- Front hallway of the Marble House.

- From the hallway looking into the middle parlor.

- Triple windows in the middle parlor.

- Fireplace in middle parlor – this tile appears old, if not original.

- Plaster crown molding in the smaller waiting room.

- View into the morning room.

- The angled walls across from the angled bay windows in the morning room.

- The window partly tucked behind a wall in the room adjacent to the morning room.

The Marble House has far more documented history than I expected to find and is a microcosm of Decatur’s growth. Its 40 acre property shrunk to about half an acre as development in DeKalb’s county seat intensified and land become much more valuable in cities’ cores. This enormous single family home became a multigenerational one as our country experienced the Great Depression. By World War II, it was subdivided into apartments (common for large intown houses during this time) and it was never used as a single family residence after that. And in the 1980s, when the state and nation began historic preservation efforts on a larger scale, it was found worthy of restoration but not as a home – it would be “adaptively reused.”

While our subject file had extensive information already, I’ve added to the research with additional newspaper clippings, copies of the plat maps from the DeKalb County Clerk of Superior Court, details of maps from our DHC archives, and copies of the materials from Bruce Hagen. It is hard to comprehend anyone having a 40 acre property within these city limits, and to learn that it was “just” a summer home also seems unusual for Decatur. This 141 year old house is truly a hidden gem in the city – I hope you have been intrigued by its rich history.

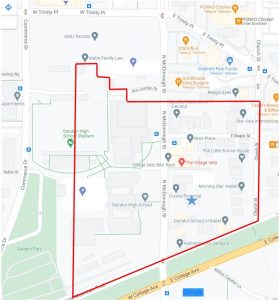

These are the approximate original boundaries for the George Walter property in 1880, superimposed over a Google Map screen grab.

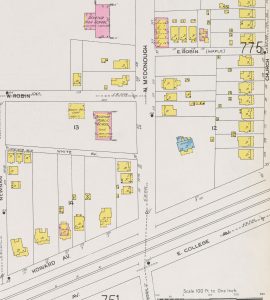

- Sanborn Maps: These maps were created to help assess risk for fire insurers and contain a wealth of information about some historic buildings. A more in-depth article on Sanborn Maps will be posted in the future. In the meantime, here are three images that show the Marble House and its environs in 1911, 1924, and about 1962. The Marble House is identified as “stone” by its blue color. As primary resources, there are occasionally some slight mistakes on the maps. This house is actually stucco over brick and Sanborn Maps do have a way to indicate an adobe veneer over a different construction material. I think this wasn’t noted as the Marble House’s technique was rare for this area. Yellow indicates frame construction, which you see on its porches as well as most of the dwellings (“D”) around the Marble House. The “x” on any structure indicates a wood shingle roof and the “0” indicates a non-combustible roof covering including metal or tile. “B” is for basement and the numbers indicate how many stories a structure has. The 1911 and 1924 maps are from the University of Georgia and are online via the Digital Library of Georgia. The circa 1962 version is a book in our DeKalb History Center Archives. Its bottom layer is a 1924 book. Changes were made by hand over time. Updates were cut and pasted into the book and are collectively so minute, they are not individually dated.

- 1911 Sanborn Map. The Marble House is the blue structure in the upper righthand corner.

- 1924 Sanborn Map. The Marble House is the blue structure in the middle.

- 1962 Sanborn Map. Now there are many more blue (noncombustible) structures on the map; many of these are concrete block. The Marble House is surrounded by dwellings that are already being converted to offices.

Blog with more Infomation about the Zachariah Daniel House: https://oldgeorgiahomes.com/