Thankful Baptist Church in Decatur

A history of Thankful Baptist Church, Decatur

By Monica El-Amin, African American History Coordinator

Religion has long been a central component of Black American life. During the 1800s, African American communities dealt with enslavement and racial segregation. Black people formed their own churches to escape the white-dominated churches and oppressive ideologies. In the 1900s, freed Black people used the church as a foundation to encourage independent, community-structured support. During the Jim Crow era, Black American churches began to provide social services for the community. The reasoning behind this was that Black Americans were socioeconomically disadvantaged when compared to their white counterparts. Due to their faith, the Black community consistently looked toward a better tomorrow and cultivated a sense of perseverance. Areas called The Bottom and Beacon Hill were where the Black community in Decatur established roots despite the ever-present threat of displacement due to racism. Yet, in this constant tension between the Black community and systemic racism, the church represents their longevity.

Thankful Baptist Church Early History

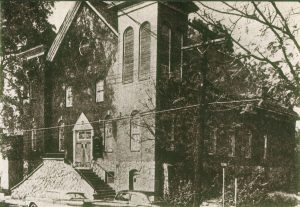

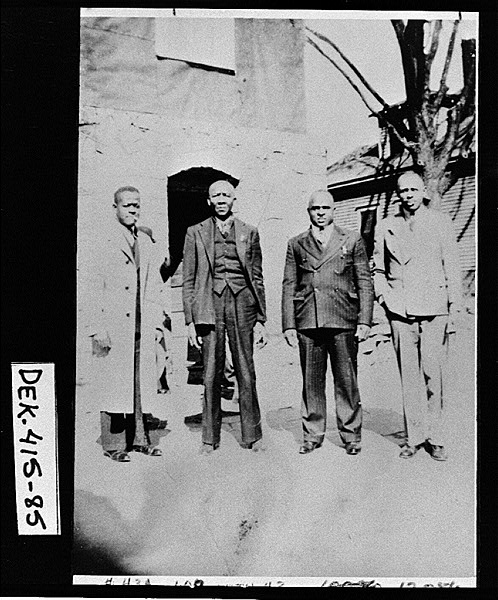

Thankful Baptist Church was founded on September 6, 1882. It was Decatur’s first Black Baptist church and was named after the Thankful Baptist Church in Augusta, GA. Its first gathering occurred at Sister Penny Houston’s house. Some of the founding members include Reverend Frank Pascal and Deacon Robert Tanksley. The church’s first minister was Reverend Lewis Thornton, a school teacher. He served as pastor for a brief period before Reverend Martin Scruggs took over. During his tenure, the church grew tremendously, and eventually, the congregation moved into a schoolhouse, located on Bennett Street.

The church outgrew the schoolhouse and built a church in what was then the 400 block of Atlanta Avenue located in the low-lying area known as The Bottom. We have not yet found the exact construction date, but it appears the brick and granite sanctuary was built in the 1920s. Plans were announced in The Atlanta Constitution in 1921 citing Leila Ross Wilburn as the architect. The church membership continued to grow over the years while leadership changed. Deacon D. G. Ebster served as church clerk for 40 years and the nearby Ebster Park (formerly an unnamed segregated park) was named after him. In July 1951, Reverend W. Leon Tucker became pastor and would serve the church for over 32 years. He ordained ministers and did community service for the impoverished.

A Mysterious Fire

Earlier research by the DHC on the Swanton House showed that Thankful Baptist Church was located within the final stages of Decatur’s redevelopment meant to address urban blight in Beacon Hill. Thankful Baptist and the Swanton House were the only two structures marked on the city’s plans as “Not to be Acquired,” which also meant the structures would not be demolished during the city’s project. At the end of Decatur’s 1960s redevelopment, all of the freestanding single-family and duplex homes that comprised Beacon Hill were demolished, and Thankful Baptist stood alone. By 1970, the rerouting of the streets during the redevelopment had cut off car access to the church from the black community. It no longer fronted any street because Atlanta Avenue was almost entirely erased from the city and new parcels were created that included the land previously occupied by the street. The congregation had no time to figure out how to proceed before an unexplained fire destroyed the building. (1)

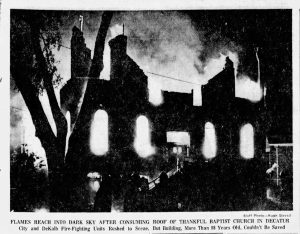

On September 23, 1970, Thankful Baptist Church was engulfed in flames. The Decatur Fire Department was notified at 5:25 a.m. Several firemen were burned while combating the blaze. Training Chief A. H. Davis, of the Decatur Fire Department, said the fire was “rough” and this was the first total loss of a building in his 25-year career. Davis said it would take two or three days to determine the cause of the fire. Analysis would be difficult due to the extent of the fire’s destruction. (2)

The following day, the newspaper reported that state arson investigators were on the scene. Decatur Fire Chief M. D. Googer assured the public that investigations were underway. When asked if there was any evidence that the fire was intentionally set, he replied, “We’ve found a little bit, but it’s not much to go on.” (3) The cause of the fire was never mentioned in subsequent newspaper articles. More than half a century later, we do not know the cause of the fire nor the depth of the investigation. What we do know is that the church had already been severed from its community, and was the only structure remaining in its vicinity.

The members of Thankful Baptist Church planned to gather and celebrate their 88th anniversary but were thwarted due to the fire. They temporarily used the Beacon Elementary School auditorium for their Sunday School and worship services. The congregation was hopeful that they would soon have another home to continue their praise and worship. Its 500 members were asked to donate money towards a new sanctuary. Decatur’s urban renewal efforts displaced church members who moved away as the total number of housing units were reduced, yet they still returned to Thankful Baptist Church. A replacement sanctuary was estimated to cost $300,000, but the structure was only insured for $50,000. Thankful Baptist Church lost its church bus in the fire too. (4)

After over a year of meeting at Beacon Hill School, Thankful Baptist Church moved into Pattillo Memorial United Methodist Church on West College Avenue on July 4, 1971. Reverend Leon Tucker, the church minister, said that although an architect had offered free services, it was more cost-effective to purchase an existing church rather than to build a new one. (5)

The following day, the newspaper reported that state arson investigators were on the scene. Decatur Fire Chief M. D. Googer assured the public that investigations were underway. When asked if there was any evidence that the fire was intentionally set, he replied, “We’ve found a little bit, but it’s not much to go on.” (3) The cause of the fire was never mentioned in subsequent newspaper articles. More than half a century later, we do not know the cause of the fire nor the depth of the investigation. What we do know is that the church had already been severed from its community, and was the only structure remaining in its vicinity.

The members of Thankful Baptist Church planned to gather and celebrate their 88th anniversary but were thwarted due to the fire. They temporarily used the Beacon Elementary School auditorium for their Sunday School and worship services. The congregation was hopeful that they would soon have another home to continue their praise and worship. Its 500 members were asked to donate money towards a new sanctuary. Decatur’s urban renewal efforts displaced church members who moved away as the total number of housing units were reduced, yet they still returned to Thankful Baptist Church. A replacement sanctuary was estimated to cost $300,000, but the structure was only insured for $50,000. Thankful Baptist Church lost its church bus in the fire too. (4)

After over a year of meeting at Beacon Hill School, Thankful Baptist Church moved into Pattillo Memorial United Methodist Church on West College Avenue on July 4, 1971. Reverend Leon Tucker, the church minister, said that although an architect had offered free services, it was more cost-effective to purchase an existing church rather than to build a new one. (5)

Black Church Fires – Why do they happen? What do they mean?

Through the course of writing this article, curiosity struck me. I began to ponder the meaning behind Black church burnings like the one at Thankful Baptist. I have heard of domestic terrorism perpetrated on Black churches but wondered why. What is the meaning of these burnings? How do they affect Black communities and their spaces? The history of church burnings in America is heavily intertwined with the need to maintain societal and racial hierarchies through fear. Similarly to cross burnings, the message is clear – Black churches are harmed because of hatred, and to threaten and intimidate congregations.

Racism in the United States burns at the fabric of the country’s core. The Black community has faced a social death regarding their place in society. The exclusion caused them to seek the church to be seen and heard while learning about the world. Black churches provided a place free from oppression and racism while creating space for social and political movements. The sermons preached in Black churches used Christianity as a vehicle to connect the struggles of everyday life, making religion a key component of the community.

However, Black churches are not a monolith and vary from region to region. There are divisions among social, political, and economic positioning. Despite their differences, these churches came together in the face of segregation and racial discrimination. Yet, the more involved Black churches were in challenging racial division, the more church members were reprimanded. As the Civil Rights Era progressed, Black churches became the social and political bases for their communities.

The Black church community was divided on how to approach the Civil Rights Movement. Some churches were opposed to involving themselves in the politics of the movement. Those who participated organized various forms of protest while intertwining them with the teachings of the gospel. Racism placed Black churches as the target of white supremacist aggression against the entirety of the Black community.

Violence has been a forceful way to communicate racial discrimination and hatred in the United States. Its usage stemmed from the white supremacist desire to enforce control over the Black community and other ethnic groups. Black churches were burned and bombed in retaliation for the Civil Rights Movement. In the decades before the Thankful Baptist Church fire, Black church burnings and bombings occurred nationwide and have continued into the present. Racial violence, and its implications, create an environment that fuels the flames of hatred against the Black community.

The role of religion in Black American life has been a powerful testament to flexibility and community. From the establishment of Black-centric churches in the face of enslavement and segregation to the emergence of social service enterprises during the Jim Crow era, the church has not only served as a spiritual refuge but also as an enthusiastic support system for socio-economically disadvantaged individuals. The story of Thankful Baptist Church exemplifies how faith and unity provided a groundwork for survival amid systemic racism and displacement. As we reflect on the church burning, it is of the utmost importance to recognize the ongoing implication of their perseverance despite such a drastic event. Thankful Baptist Church represents a beacon of hope that they will remain firm and stay afloat despite the difficulties.

Notes:

1. “A Decatur Treasure,” Times of DeKalb, Newsletter, Spring 2014.

2.“Firemen Injured as Church Burns,” The Atlanta Journal, September 23, 1970.

3.“Church Ruins Inspected for Arson Clues,” The Atlanta Journal, September 24, 1970.

4. “To Rise Again from Ashes – Church to Mark 88th Anniversary,” The Atlanta Journal, October 14, 1970.

5. “Thankful Baptist to Occupy New Church Quarters,” The Atlanta Journal, June 23, 1971.

Sources:

Butler, A. (n.d.). The Black Church. PBS. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/godinamerica-black-church/

Carter, Carolyn S. “Church Burning in African American Communities: Implications for Empowerment Practice.” Social Work 44, no. 1 (1999): 62–68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23717892.

Michele M. SimmsParris, What Does It Mean to See a Black Church Burning? Understanding the Significance of Constitutionalizing Hate Speech, 1 U. Pa. J. Const. L. 127 (1998).

Available at: https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/jcl/vol1/iss1/4

Keller, Jared. 2015. “The Ongoing Destruction of Black Churches.” Pacific Standard. July 7, 2015. https://psmag.com/news/why-the-destruction-of-black-churches-matters/.

To Be Equal: Hate Crime Surge Continues With Burning of Black Churches (no date) To Be Equal: Hate Crime Surge Continues With Burning of Black Churches | National Urban League. Available at: https://nul.org/news/be-equal-hate-crime-surge-continues-burning-black-churches (Accessed: 01 October 2024).