Of the Land: A Glimpse at Georgia’s Early Indigenous Peoples

Read on to learn about the early human history of Georgia as well as the early history of the Cherokee and Creek Nations before European arrival. This post is not all-encompassing – it merely scratches the surface when it comes to early humans in the vicinity of today’s Georgia and the deep-rooted history of the Cherokee and Creek Nations.

By Rebecca Selem, Exhibits & Communications Coordinator

Human habitation in the area we now call Georgia is thought to have begun around 15,000 BCE. These groups, called the Paleo Indians, were nomadic bands of hunters who predominantly hunted Ice Age megafauna. As the climate in the southeastern part of North America began to warm, humans were able to thrive in the area of the Macon plateau, hunting deer and fish and gathering berries, nuts, and roots for sustenance. This group is known as the Archaic Indians, frequenting the area until about 1000 BCE. Due to their differing lifestyles, the artifacts and stone points they used varied from their predecessors.

Soapstone Bowl, Archaic Period (9600-1000 BCE). The early residents of the area created a soapstone trading enterprise from 3000 to 1500 BCE. They created bowls, slabs, and other tools to trade as far as Louisiana and the Great Lakes. It was a very successful industry until the use of ceramics spread, a lighter more efficient alternative, making soapstone obsolete. Soapstone Ridge Historic District is located in southern DeKalb County. From the DeKalb History Center collection.

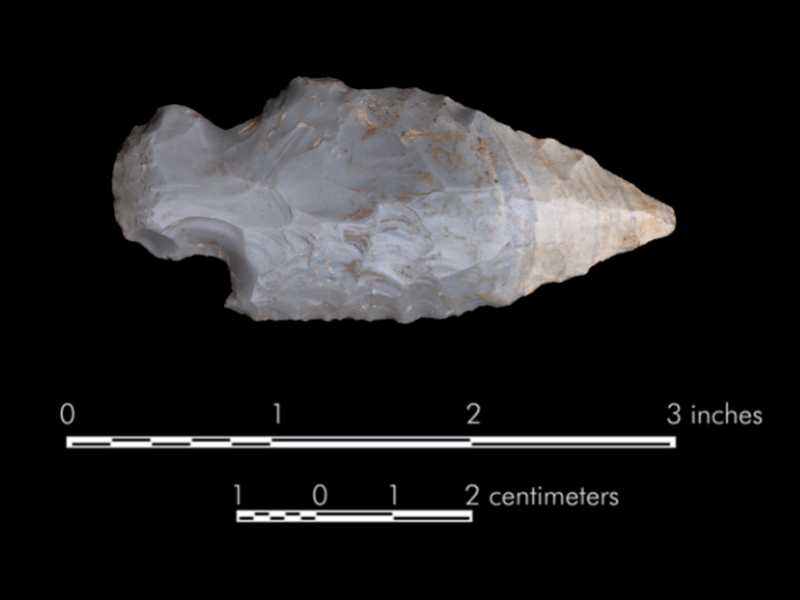

Projectile Point or Knife, chert, Beacon Island point type. The flaking technique used in making this point is ideal for hunting or weaponry. The Beacon island point type is associated with the late Archaic (4000-3000 BCE) to the Woodland (3000-1300 BCE) periods in the southeastern United States. From the DHC collection. Photo provided by New South Associates.

The Woodland Indian period, beginning after 1000 BCE, brought in the trend of creating permanent settlements, no longer roaming the land nomadically in search of food. This group figured out how to successfully sustain horticulture, securing more reliable food sources and allowing them to live in one location. They planted starchy seed plants, like grasses and sunflowers. Due to their immobility, they developed more permanent tools, buildings, and art, and began a trading system with other groups – some as far west as the Rocky Mountains and as far north as the Great Lakes.

The Mississippian Culture began around 900 (CE), and by 1200, different groups within the culture moved from the areas of central Georgia and thrived in different locations such as Etowah in north Georgia, Moundville in Alabama, and Spiro in Oklahoma. Those who lived on the Macon plateau moved a few miles south from the Ocmulgee Mound Complex and established the Lamar site around 1350. The Lamar Culture is an example of late Mississippian culture and is named after an early landowner in the area. This particular group of people are thought to be the direct ancestors of the Muscogee (Creek). The group that migrated up to Etowah are thought to be the ancestors of the Cherokee.

The Lamar people thrived until 1540, when Hernando de Soto led an expedition into the southeast bringing unfamiliar diseases like smallpox and using violence and terror in his quest for riches. Exposure to the Spaniards decimated the population and survivors of this catastrophe banded together to form the Ochese Creeks and the Muscogee Creeks, names historically known to English settlers. It is estimated that as much as 90% of the country’s Indigenous population died as a result of Europeans coming to America.

Print of Hernando de Soto. Courtesy of New Georgia Encyclopedia.

Pre-European Arrival

Muscogee (Creek)

The groups that made up the Creek Confederacy were the Muscogees, Yuchis, Alabama, Hitchiti, Shawnee, and others. As a whole, the group was identified most frequently as the Muscogee because they made up a vast majority of the confederation. Interestingly, those who made up the Muscogee (Creek) Nation spoke a number of different languages – such as Algonquian, Muskogean, or Siouan.

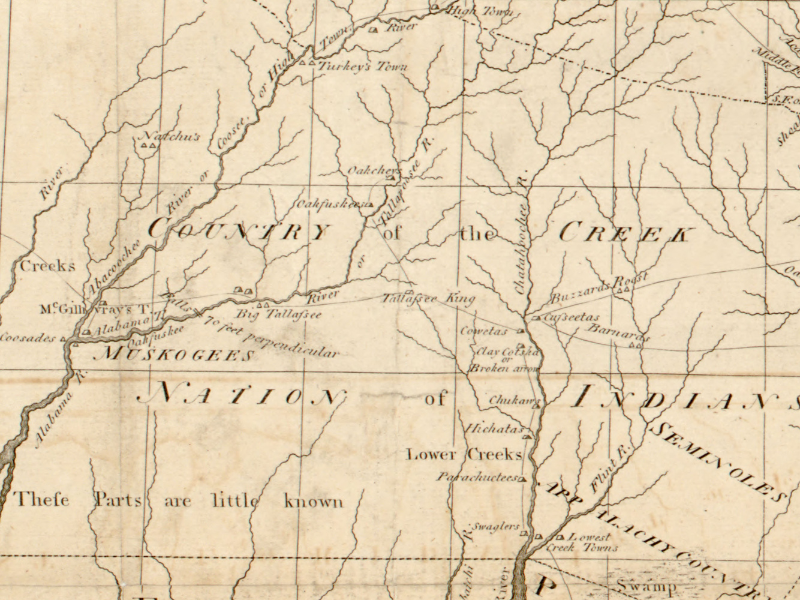

The Muscogee (Creek) territory once stretched from the Georgia coast into what is now central Alabama.

Members of the Nation were nicknamed “Creek” by British settlers in the 1700s because they were always situated near a creek or river. As the nickname suggests, the Muscogee (Creek) towns were rooted in river valleys, or near flowing water of some kind. Towns were typically organized around a main public area with villages surrounding it. Sacred earthworks or mounds were the social centers of town with community gardens and fields of crops stretching past the town. The central plazas would often contain four partially enclosed wooden lean-tos or open cabins in each cardinal direction – used for the principal chief, a second subordinate chief, and a council of elders to meet. The head families would reside close to the center of town. Villages had flat, square grounds surrounded by arbors for ceremonial dancing purposes.

The government of the Nation consisted of a General Council composed of head men from each town (chiefs and subordinate chiefs) – they decided matters of war and peace for the entire Nation. However, many towns did not follow the direction of the General Council and kept to themselves. By the mid-1700s, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation contained about 60 towns.

Map of the province of Georgia showing trails and paths for trading and locations of indigenous groups. This image is a closeup of the Creek Nation’s territory. Published in 1779. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Women tended to the crops (corn, beans, squash, etc.), while men hunted, fished, and traded with neighboring tribes. They gathered berries, nuts, wild plants, and roots from surrounding forests for nutritional and medicinal use. Diets likely consisted of meat (deer, squirrel, turkey, fish), corn prepared in a variety of ways, nuts, and fruits and vegetables like dewberries, blueberries, muscadines, squash, sweet potato, pumpkin, and beans. Salt was critical in their mostly agricultural diet.

Women held a prominent role in Muscogee (Creek) society before European influence. They were considered the heads of the household and held ownership of the homes and land. When daughters got married, they built their homes on family land.

Within the different towns, there were different clans. Clans usually stayed together in a household group and lived near one another.

The town square was at the center of the Muscogee (Creek) social, political, and religious life. In the middle of the town square sat the sacred fire with four logs. Ceremonies were held in the town square in front of the sacred fire. One of the major ceremonies that took place annually was the “Busk” or Green Corn Ceremony, which was to renew purity and balance in the tribe’s spiritual life. The Green Corn New Fire is said to restore order and balance from the chaos created in the past year.

View from the Great Temple Mound at Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park overlooking Walnut Creek. March 2022.

Cherokee

The Cherokee Nation’s traditional homelands occupied present-day western North Carolina, eastern Tennessee, the northwestern corner of South Carolina, and parts of north Georgia – with its center in the Great Smoky Mountains. These ancient lands are where the Cherokee creation story is said to have taken place. The river valley in Cullowhee, North Carolina, has been inhabited for thousands of years by the Cherokee, and Kituwah is identified as the first Cherokee town.

The Cherokee way of life before European contact was in many ways similar to the Muscogee (Creek). They too resided in river valleys in agricultural villages. Villages held around 12 to 60 families. At the center of the village stood a circular structure, called the townhouse or council house, which served as a meeting place. The townhouse often sat atop an earthen mound of about twenty or thirty feet tall. Inside was a central hearth with a fire surrounded by sections of benches. The townhouse was built to be large enough to hold everyone in the village. Also central to Cherokee towns were large, open outdoor spaces dedicated to ceremonial dancing and games like stickball and chunkey.

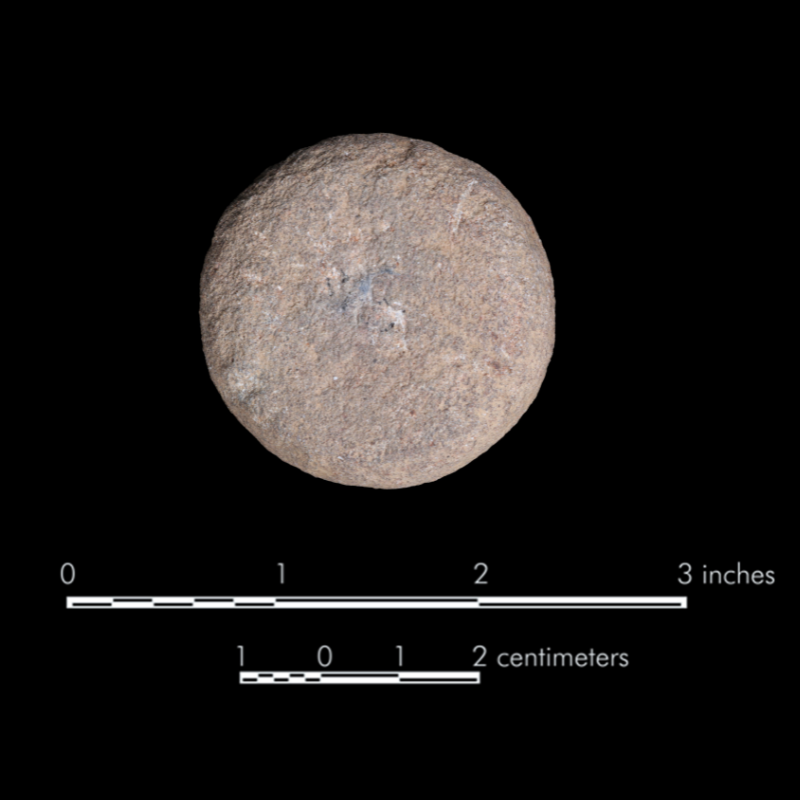

A stone disk like this one is thought to have been used for recreational purposes within indigenous communities. Games like Chunkey were commonly played by boys and older men. The goal of the game was to roll the disk and try to throw your spear closest to where the disk landed. From the DHC collection. Photo provided by New South Associates.

Agriculture was central to indigenous lifestyle and culture. Surrounding the village were gardens and fields of corn, beans, tobacco, sunflowers, and greens. Families typically had their own fields of crops and food storehouses, but they also contributed to a village plot and storehouse. These additional resources went to the old, the sick, visitors, and were kept in case of emergency. Along with the crops they grew, they also gathered fruits, nuts, and wild plants. Plums, berries, and persimmons were eaten fresh and dried. Walnuts and hickory nuts were an important source of fat for their diet. The surrounding land and forests provided them with ingredients for natural medicines, and fiber for cordage and woven textiles.

In the village gardens, old women would sit on raised platforms to scare off any wildlife that may attack the gardens or cornfields. They took this job very seriously. Cherokee also hung gourd birdhouses near the gardens to attract purple martins. They ate insects notorious for destroying crops.

Cherokee women were in charge of the farming, gardening, and were heads of the family. Men hunted, traded, and protected the village from outside threats. Boys began learning how to use the bow and arrow and blowgun around the age of three.

Traditionally, women held equal power with men. In fact, Cherokee society was based on the female line. Houses and land were owned by women and were passed to female relatives. After marriage, men moved into their wives’ homes, at the wife’s discretion, and upon divorce, men moved in with female relatives – sisters or mother – and children stayed with the mother.

The Cherokee lived by a clan system that forged their relational, political, social, and religious structure. There were seven clans – each headed by a clan mother and served as an extended family. Clan membership passed through the mother’s lineage. Clans were in charge of the law and order of their members. In 1808, however, the Cherokee National Council changed that responsibility and shifted property ownership, and the nation as a whole, to a patrilineal society.

Mounds at Etowah Indian Mounds State Historic Site. November 2021.

Prior to European contact, Cherokee typically wore clothing made from tanned hides or woven cloth, often decorated with beads and shells, with traditional decorated moccasins as footwear. Women wore knee length cloth skirts, often paired with a decorated deerskin cloak or a feather cape for warmth. Men wore a cloth between their legs, similar to a loin cloth, which was attached by a cord worn around the waist. Capes and cloaks were worn in the colder months. Deerskin leggings were worn by both men and women in the winter months – these only covered the leg from the ankle to above the knee. Jewelry made of shell, copper, and silver was worn, and many Cherokee had tattoos.

Like the Muscogee (Creek) the Cherokee also celebrated the Green Corn Ceremony. For the Cherokee, this celebration served as a kind of New Year and Thanksgiving. Held every year in mid-summer, when the sweet corn was ready to eat, and in October, when the field corn was ready to be picked. During the festivities, Cherokees prepared themselves for the new year, cleansing themselves physically and spiritually before feasting with the village. They gave thanks for the harvest and performed special dances and songs.

Part 2 will discuss the history of the Cherokee and Creek Nations after European arrival, the changes that took place, and the struggle to hold on to their ancestral homelands and fight removal to the West. This is one of three upcoming posts.

Author’s note: I am not an expert in this field of study, so please contact me with suggestions or additional information.

Resources/Sources

https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/cherokee-indians/

https://www.nps.gov/ocmu/learn/historyculture/hernando-de-soto.htm

https://www.nps.gov/ocmu/learn/historyculture/paleo-indian-culture.htm

https://www.nps.gov/ocmu/learn/historyculture/the-muscogee-nation.htm

https://mci.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/INFORMATION-PACKET-pdf.pdf

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLZcZfJCSCxq-qLFtfne3i9Nyf0kb1GISC