Scrapbooks Part 2, Cultural Legacy

Scrapbooks are a curated way to display the things that people were most passionate about. Moving into the twentieth century, people began collecting items from their own life.

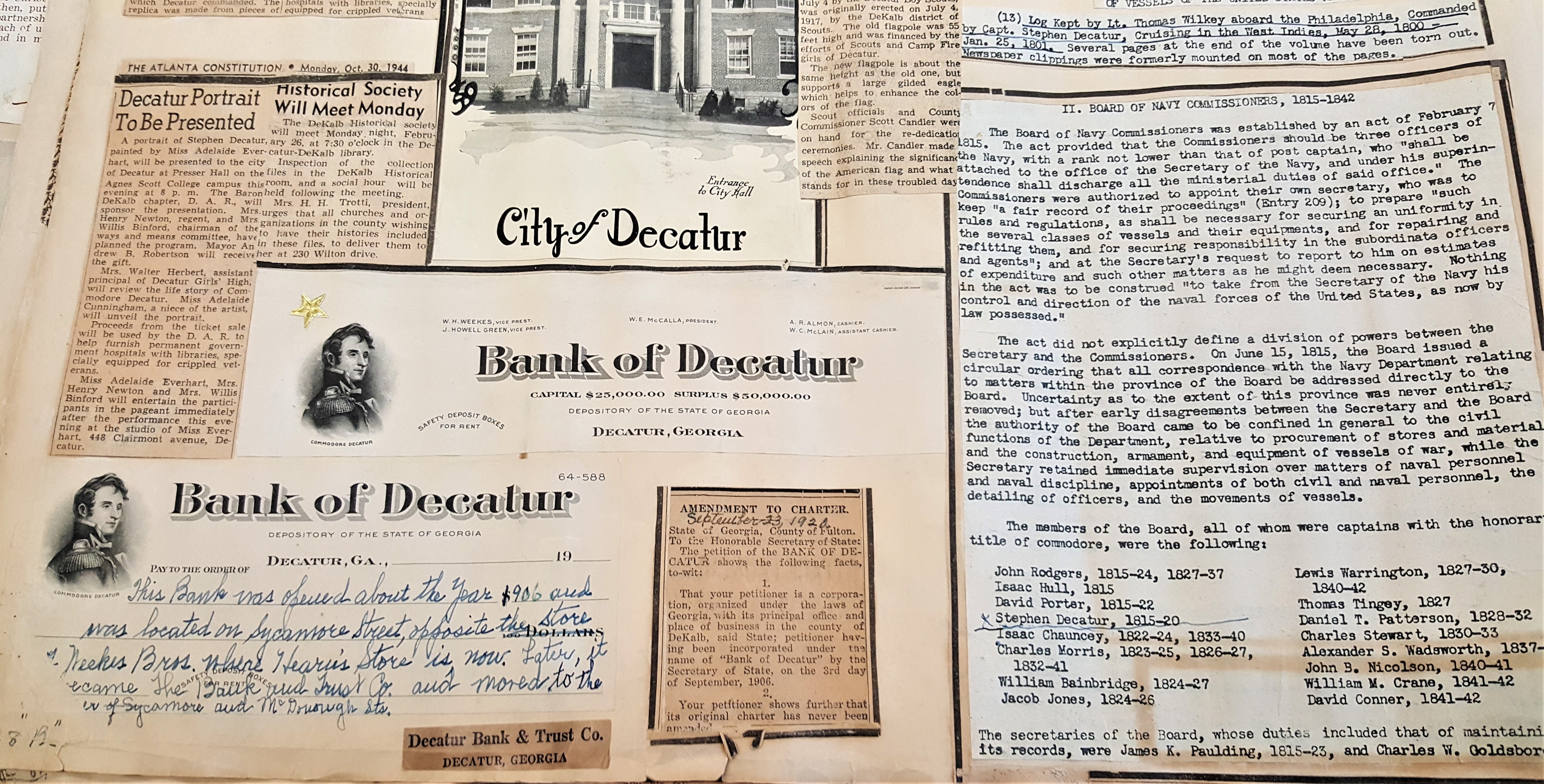

A scrapbook from the DeKalb Historical Society that relays the history of the county from the 1880’s – 1955 (Image courtesy of Samantha Mooney)

“My dad takes most of the pictures in our family, and he makes scrapbooks. This means he gets to figure out what’s important for us to remember… I guess my mom could make a scrapbook, but she doesn’t. And I could do it and so could my brothers… I know the scrapbooks we’d make would be different from Dad’s. But the person who does the work gets to write the history.” – Holly Sloan, Short

Scrapbooking seems geared to a mature audience. Younger generations rarely develop nostalgia because they live in the present. Age causes a greater cognizance that time is fleeting. This can cause a desire to capture special moments, either for those who will live beyond or as a hobby for the self, a genie-in-the-bottle cure-all to commemorate important things in daily life.

Early scrapbooking was a method to sift through and organize the onslaught of information. Beginning in the 19th century, reading proficiency grew exponentially. Newspapers became a cornerstone of society, creating a populist literary culture. Yet, people fretted about the transience of new literary forms such as magazines and newspapers. Colored ink became widely available, and people liked its rich aesthetic potential. In a culture that was changing, readers needed a way to capture the best parts so they pasted and collated them into the familiar form of a book. Interests ranged widely: housewives documented effective stain removers and home remedies while morbid newshounds made clippings of the most gruesome obituaries. Newspapers began featuring columns named “For the Scrapbook.” This was a “retweet” button before its time, a way to influence popular thought. Newspapers tried to anticipate what scrapbookers would be most interested in and competed to garner the widest circulation.

Scrapbooking was a precursor to social media. It had the functions of Pinterest or Tumblr, a method organize the onslaught of information and preserve the most important for later access. A whole lexicon developed around practices. Like “pinning,” tweeting, and “posting,” scrapbookers preserved “gleanings.” Scrapbooking is perhaps the most like Tumblr, a curated way to display the things that people were most passionate about. Moving into the twentieth century, people began collecting items from their own life. People often ‘causally’ left their scrapbooks in high traffic areas such as the parlor table where people would just ‘happen’ to see them. This allowed for a curation of lifestyle akin to Instagram and Facebook.

A design scrapbook featuring a sketch of a 1950’s dress and photo (Samantha Mooney)

Scrapbooks may seem like an unconventional resource to use in historical research; in truth, they are a record of cultural history. They reveal aspects of society that are largely undocumented. Newspapers give glimpses into how people across the country reacted to current events. A menu or food ticket reveals what people ate, at what price. A seed packet can show what people planted in their gardens. Was the family wealthy enough to afford exotic roses or did they need a vegetable garden? Archivist Fred Mobley states that “Scrapbooks are a marvelous record of our cultural history… the construction shows the period and practices… and serves as a repository for future generations on what life was like and how people lived.”

Most scrapbookers were women. This remains true: women exceed the number of men present on social media platforms (with the exceptions being Twitter and Youtube.) Since the advent of scrapbooking, minority groups used it to share and preserve their history. Suffragettes faithfully recorded their collective actions. Frederick Douglass enjoined black Americans to scrapbook. The books served as a community reference: documenting crime statistics (African-Americans were not able to access them due to segregation) and to cultural excellence and daily life. In face of their history being ignored and undervalued, minorities established their own historical record. The Smithsonian acutely observed that scrapbooks “were an act of self-definition… [turning people] into documentarians. People had this impulse to remember, and to guard what they knew.”

Preserving this history poses a significant challenge for archivists. The majority of scrapbooks use mixed media which does not age well. The glue turns rigid and yellow, often causing items to ‘pop’ off the page. This can destroy the integrity of the artifact, causing further conservation issues. When objects become detached, it can become difficult to determine the original placement. Newspapers are especially troublesome: low-quality wood pulp paper is brittle, prone to breaking. Most paper is acidic, causing discoloration. Sometimes paper can fall apart in your hands. Metallic elements can rust, causing further paper deterioration.

Mobley expressed that “From an archival standpoint, [scrapbooks] are disastrous to [maintain] the longevity of the material. Scrapbooks, in general, are not easy to preserve.” Mobley recommends that the best way to preserve historic scrapbooks “is to reduce the actual, physical use of the scrapbook by making digital copies.” Despite their difficulty, scrapbooks are an integral part of archival research, illustrating everyday life across diverse groups. They tell stories of all people. There is something tangible, powerful about being able to hold history. Even in a digital age, that still remains true.

Written by Samantha Mooney

Works Cited:

Sloan, Holly Goldberg. Short. New York: Puffin Books, 2018.

“The 2018 Social Audience Guide.” Spredfast. 2018. Accessed August 03, 2018.

Thompson, Clive. “When Copy and Paste Reigned in the Age of Scrapbooking.” Smithsonian.com. July 01, 2014. Accessed August 03, 2018.