Stiffs for Science: Life After Death

The history of the departed in the Victorian Era.

By Marissa Howard, Programs and Membership Coordinator and Rebecca Selem, Exhibits & Communication Coordinator

When digging around for research on the subject of cemeteries and funerals you inevitably will come across truly macabre history. And so, the following may be hard to read but read on … if you dare.

The medical sciences were changing fast in 19th-century America. The American Medical Association formed in 1847 to formalize education and medical licensing in the United States. A new requirement was mandatory anatomy courses as a prerequisite for a medical degree, and all schools faced difficulties in acquiring the needed cadavers. In Europe, laws allowed unclaimed bodies to be donated to medical schools. In the United States, anatomy laws, or “bone bills,” had only been passed in a few states, including Massachusetts. By 1900, there were 160 medical colleges around the United States; the epicenter for medical colleges was Baltimore. Bodies for these medical colleges were in high demand. Unsurprisingly, Baltimore became the hotbed of body snatching.

Body snatching was happening at an alarming rate. It garnered headlines in newspapers all over the country. It was the subject of non-fiction short stories, like the Robert Louis Stevenson work, The Body Snatcher (1884), later adapted to film starring Boris Karloff in 1945.

A good subject – or “stiff” – as they were called, could bring in $100 ($3,000 in 2024). The ideal cadaver was, for lack of a better word, fresh. City cemeteries like Decatur Cemetery were guarded and protected, some of the graves even had metal cages or vaults. It was at private, rural, or county cemeteries where the risk of snatching was greatest. Many of these rural cemeteries were African American. Jewish cemeteries were also at risk because the bodies were typically required by Jewish law to be buried within 24 hours of death.

Despite guards, Decatur Cemetery was still robbed. In January of 1886, a janitor from the Atlanta Medical College was caught robbing the grave of Israel Sanford. Two weeks later, the body of Simon Read went missing. All that was left in his coffin were his breeches. Both graves were from “God’s Acre,” the Decatur Cemetery’s pauper grounds.

The iron gates surrounding the grave of Emily E. Pittman (1831-1852). Gravesites were frequently surrounded by fences for protection from animals or graverobbers. Its unknown when this fence was erected. This gravesite has been restored by the Friends of Decatur Cemetery. Wynne Christensen Collection, c. 1991, DeKalb History Center Archives.

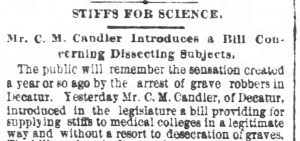

In 1886, Charles Murphy Candler introduced to the legislature a bill providing “stiffs for science” so medical colleges would have a legitimate way to acquire cadavers without grave robbing. The bill would also make the business of body-snatching a felony. Doctors who procured cadavers legally would have them buried at public expense, but the colleges would have to embalm each body and keep it for 90 days to be delivered to any relative or friend if claimed.

With the new law, grave robbing of “stiffs” was declining, but the business of what to do with the body after science remained. As mentioned earlier, the bodies were held for 90 days until claimed by the family. Often, these bodies were unclaimed. Undertakers were responsible for transport and burial.

Atlanta Constitution, November 10, 1886.

Of many of the stories I have come across in researching this story, the grimmest of all was in 1903.

Atlanta Journal, March 21, 1903.

“18 Headless Bodies Left On A Roadside”

March 21, 1903, Atlanta Journal

Two wagons containing the remains of 18 headless human bodies from the Eclectic Medical College and Atlanta Dental College were discovered on the Chattahoochee car line (Hollywood Road) between Atlanta and Hollywood Cemetery. The boxes contained bodies, minus the heads, which were removed for use at the Atlanta Dental College. The college had obtained the services of David T. Howard & Sons Undertakers to bury the bodies. The workers Howard sent to retrieve the bodies ran into issues on the road when a rain storm took out their horses and got stuck in the mud. The people living in the neighborhood “seriously objected” to having a wagon load of decaying human bodies in front of their houses all day and night. Some of the boxes were broken, with bodies and feet hanging out of the ends of the box.

The wagon drivers were arrested, one of them was 14 years old.

The bodies were interred in Southview Cemetery a few days later.

The increased usage and affordability of embalming, which enabled medical schools to keep bodies for months, was the final nail in the coffin for body snatching in the 19th century.

Pallbearers at a funeral c. 1920. Photo courtesy of A.S. Turner & Sons Funeral Home.

Into The Vat

The new law stated that all unclaimed bodies were to be given to medical colleges. If the body was identified, the name was published in the newspaper to see if someone would claim it. One such identified body was Edward Flanaghan. Flanaghan was convicted of a double murder in DeKalb County in 1896. His body went unclaimed and was turned over to the Georgia College of Eclectic Medicine and Surgery. Ten years later, students at the college discovered Flanaghan in a “pickling vat.” He was described as feeling “like a rock” and the students jokingly said that in order to dissect the body they needed to call in granite cutters from Stone Mountain. It is not known what happened to his body afterwards. Most likely he is buried in an unmarked potter’s field.

A note on “pickling vats.” It is exactly how it sounds. The pickled body was placed in a vat or barrel of alcohol and/or other chemicals for preservation. Sometimes nitrate pickling salts were also used. This preservation method was primarily for science or out of necessity. Vice-Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson may perhaps be the most famous example of pickling. Lord Nelson died at sea in 1805 at the Battle of Trafalgar, and the ship’s surgeon preserved Nelson in a barrel of brandy for the ride back to England. This was unusual, as most dead would have been buried at sea. To the alarm of the surgeon and everyone on board, the barrel began to swell with air. The barrel needed to be tapped to release pressure, giving birth to the folklore of “Tapping the Admiral.” Upon arriving home, Lord Nelson’s body was worse for wear, and the surgeon was criticized for not putting him in rum (the claim was that rum was better for preservation). But this story was sensational enough to create legends and folktales. Sailors desperate for alcohol, resorted to tapping Lord Nelson for a “stiff drink” … supposedly. Like most folktales and origin stories of common expressions, it is impossible to know if the brandy that was tapped from Lord Nelson’s barrel was consumed. If you would like to pay tribute to the legacy of Lord Nelson, there are several cocktails named in his honor all featuring a heavy dose of rum tinged with blood red liquor.

Brief History of Embalming

At the turn of the 20th century, embalming was becoming the method du jour for preserving bodies. Embalming is defined as a method “to treat so as to protect from decay.”

The practice of embalming has been around for thousands of years – it is considered “one of humankind’s longest practiced arts.” Preservation methods since ancient times have varied from immersion in honey, wax, and alcohol to the arterial injection of arsenic, formaldehyde, or nontoxic chemicals and essential oils.

Embalming started to spread more widely in the United States after President Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train made its way from Washington, D. C., to Springfield, Illinois, in 1865. The train stopped at major cities along the way and the nation witnessed the extraordinary capability of embalming to make the deceased look remarkably alive. Lincoln was the first president to be embalmed.

President Lincoln’s funeral procession, 1865. From the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

As embalming increased in popularity, the need for certified embalmers also grew, since the average person could not embalm the dead on their own. The practice quickly became regulated and schools offering certifications became more widespread.

Before the Civil War, dealing with death was a common but private affair. When someone died, neighbors would gather to help clean and dress the deceased and someone would stay with the body for 2-3 days to make sure they were truly dead. Then they would help dig a grave on the property or in the local church graveyard. Into the early 1900s, funeral practices were done solely at home. If a licensed embalmer lived in town, they would come to the deceased’s home and embalm them there.

Around the 1900s, the funeral business took off. Many local hardware stores that already sold coffins began offering additional services like embalming, horse and carriage transportation, and more, often transitioning completely to a funeral home in later years. A local example of this transition is A.S. Turner & Sons Funeral Home.

By the mid-1900s, people in and around DeKalb County were conducting business with the local funeral homes whenever death occurred.

Turner & Everitt Hardware Store, circa 1915. This building was located on North McDonough Street, directly across from the present new DeKalb County Courthouse. From A.S. Turner & Sons Funeral Home.

Additional Reading

https://www.funeralbasics.org/the-strange-unusual-history-of-embalming

https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2022/09/evolution-of-american-funerary-customs-and-laws

https://www.asturner.com/about-us/our-history

https://www.facs.org/media/1x0f0byz/03_grave_robbing.pdf

https://oaklandcemetery.com/stiff-stealers/

https://fords.org/lincolns-assassination/impact-on-a-nation/lincolns-funeral