Mourn Like a Victorian

Read on to learn more about American mourning customs of the Victorian Era.

By Rebecca Selem, Exhibits & Communication Coordinator

“Many people did not fear death; rather, they feared not being ‘properly’ mourned.”

Death was no stranger to those living in pre-modern America. It happened often and mysteriously. In the 19th century, the average lifespan was 50 years, with one of every three children dying before the age of 10. Prior to the Civil War, death was a private matter and was dealt with quickly and respectfully.

A notable trendsetter of the 19th century was Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. In December of 1861, she began grieving the death of her husband, Prince Albert. She remained in mourning for the rest of her life, wearing mostly black until her death in 1901.

Queen Victoria, 1862. From the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

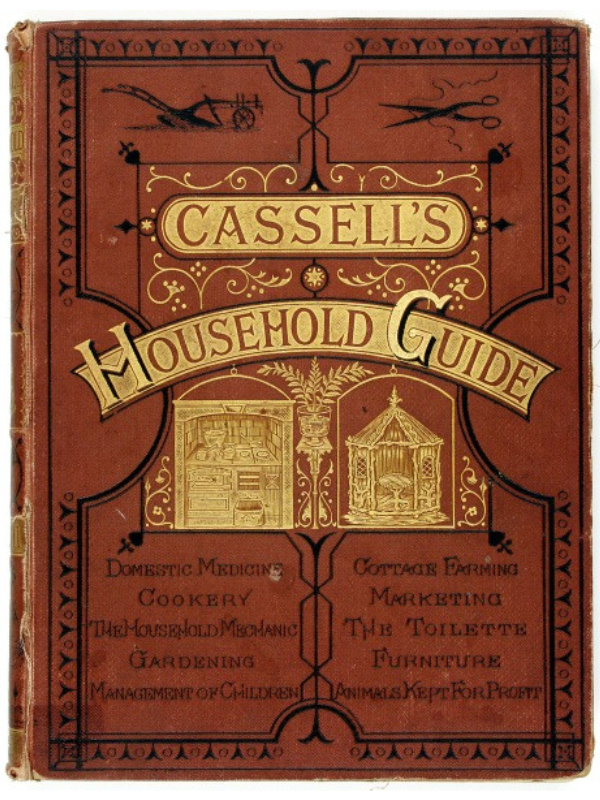

Queen Victoria’s influence, along with a devastating war raging in the U. S. during this time, influenced American customs. Mourning etiquette developed by Brits was soon followed by Americans. This included complicated and detailed instructions for who wore what and for how long, as well as what arrangements to take before and after someone died. Journals and household manuals like Cassell’s Household Guide, published in 1869, provided expertise on virtually any topic, including mourning etiquette.

Cassell’s Household Guide, published in 1869.

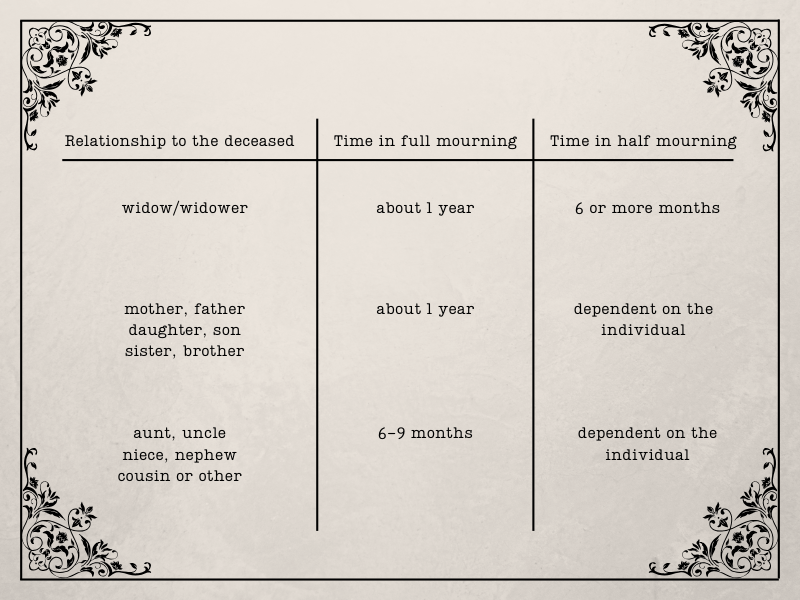

Mourning became a public experience rather than a private one. Along with performing a number of tasks in the home, family members of the deceased were expected to dress in full mourning attire for a specific amount of time. Periods of mourning were meant to reflect the natural periods of grief, and length of mourning depended on the relationship to the deceased.

Black was typically worn while in deep mourning. White dresses with black trim were acceptable attire in the hotter months of the year. Men’s attire did not change much – they wore black suits along with black gloves, hatband, and ascot. The width of the hatband determined the relationship to the deceased. For instance, a widower would wear a seven-inch-wide hatband while a man grieving the loss of a cousin or aunt might wear a three-inch hat band. Children did not usually dress in mourning clothes.

Gray, purple, mauve, and white are colors associated with half mourning, indicating a slow recovery from deep sorrow or the distance of a relationship to the deceased. Clothing color would lighten as mourning went on.

The death of Queen Victoria also brought about the “death” of mourning etiquette. At the turn of the century, medicine became more advanced and people began trusting hospitals to care for their sick and dying loved ones. The world became too busy for people to dwell in sorrow and they were encouraged instead to look to the future.

Death once again became a private matter, and people in the modern era are encouraged to mourn to themselves. There is a societal discouragement from expressing too much grief and one must decide personally how to deal with it when it arises.

Death is no longer a constant companion. Modern medicine has attempted to tame death by prolonging life even at the expense of quality of life. Western society often ignores or fears death because it is so far removed from our daily routines; this often leaves people unprepared when death touches their lives. Fears surrounding what happens to us after we die have not lessened with the improvement of science. An afterlife has not been proven or disproven by science. For some, this provides hope while for others the fear of the unknown scares them the most.