Eclectic Medicine, Early Medical History of DeKalb County

Five and a half decades passed between the founding of DeKalb County in 1822 and the founding of Atlanta in 1877. During this time, DeKalb County was a remote and forested area, a full day’s journey from the state capitol at Milledgeville 90 miles to the southeast. On this frontier landscape, most of DeKalb County’s early doctors relied on plant-based remedies. Their healing techniques were referred to as eclectic medicine, a branch of medicine that used “noninvasive therapies and healing practices.” The heyday of eclectic medicine occurred across the US during the second half of the 19th century and was particularly popular in rural areas. But where did the theory of eclectic medicine come from? How and why was it practiced in DeKalb County?

Eclectic medicine, like most medical theories before the 1890s – when germ theory was widely accepted – relied on the balance of humors to restore health. The Eclectic physician aimed to provide healing therapies that were in harmony with the body’s natural curative properties. They primarily used plant-based drugs that were indigenous to the United States. The Eclectics rebelled against the old invasive medical practices primarily those supported by American’s best known 18th century physician and founding father Dr. Benjamin Rush.

From the mid 1700’s through the turn of the century, Dr. Rush and many of his Anglo-American and English colleagues practiced medicine based on the humoral theory. This was the belief that illness was caused by imbalances in bodily fluids – also known as humors. Doctors who embraced the humoral perspective studied fluids such as urine, vomit, and blood for signs of health, and prescribed treatments such as bloodletting and vomiting in hopes that this would restore the character of those fluids into their proper balance.

One type of treatment for humoral imbalance was heroic therapeutics, which meant practicing the standard medical treatments to extremes, such as bleeding a patient until he fainted, or purging her to the point of causing extreme weakness.

Bleeder, DHC Collections

Dr. Rush employed this practice during the 1793 outbreak of Yellow Fever in Philadelphia. He estimated that the average person contained 25 pounds of blood and recommended that up to 80% be removed.

Over the course of “the 100-day Yellow Fever epidemic, there were at least 4,044 deaths in Philadelphia.” Two centuries later, researchers “made an effort to identify by name as many of Rush’s patients as possible and to track outcomes of his management. It is estimated that 46% of Rush’s patients died.

Despite the fact that probably more than half of Rush’s patients did recover from both Yellow Fever and the doctor’s purgings, reports on patient symptoms and treatment results might have raised serious doubts about the effectiveness of his methods, and many of Rush’s peers in the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, openly questioned his treatments.

In 1826 Dr. E.N. Calhoun was one of the first recorded doctors in DeKalb County. He applied heroic therapeutics to patients with Typhus and Typhoid Fever. Prescribing what he called the “black dose,” Dr. Calhoun treated patients with a concoction that included calomel – a form of mercury chloride often used as an ingredient for purging, who’s toxic effects also produced salivation, gum inflammation, loosening of the teeth, gastrointestinal upset, and an ashen appearance, arm and facial tremors, and personality change. He mixed this with quinine (which is used to treat malaria, today), capsicum also known as red pepper or chili pepper, camphor oil (used today for insect repellant and embalming fluids) and the narcotic opium.

Quinine, DHC Collections

Over the course of the next three decades yellow fever, typhus, and typhoid would continue to wreak havoc in urban areas and by the 1830s when the new epidemic of cholera caused heightened panic and heightened mortality rates traditional medical treatments of bloodletting and vomiting exacerbated dehydration and hastened death.

Trust in doctors who were predominately using heroic therapeutics was quickly waning, and as more and more people were moving onto the frontier and expanding America’s territorial control. This expansion meant that they did not have access to formally trained medical doctors or pharmacies and so they started to rely on natural cures.

For example, in 1832 “When medicine was unobtainable” DeKalb County doctor “Philip H. Buford used herbs from his own garden as well as those from nearby forests from which his medicines were made.” By this time the precursor to Eclectic Medicine claimed 1.5 million adherents – or close to 12% of the population in the United States.

Dr. Powell’s Medicine House.

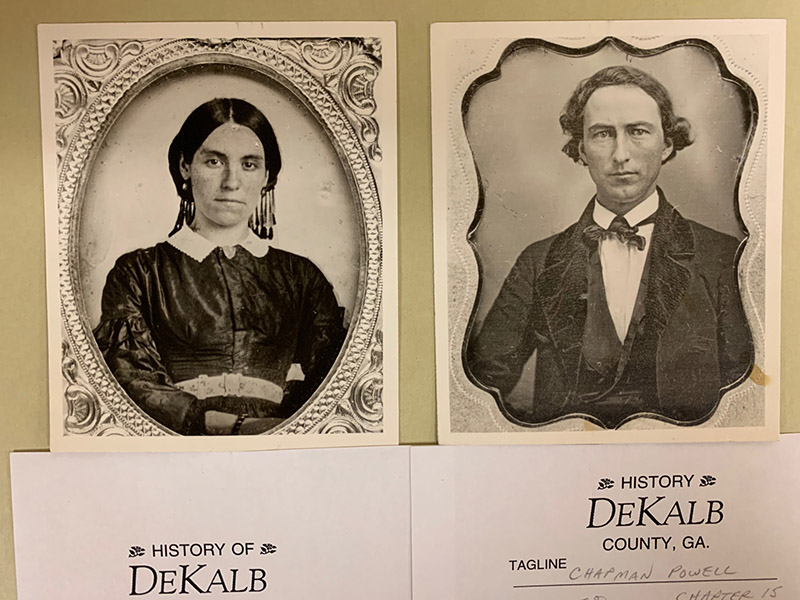

In 1833, DeKalb County doctor Chapman Powell and Mrs. Elizabeth Hardeman Powell built a log cabin home on the section of Shallow Ford Trail now known as Clairmont Rd. Powell’s home became known as the Medicine House. Dr. Powell’s medicines often included a gallon of whiskey as the first requisite in which to mix the pulverized roots and herbs.” The result of this process in compounding medicines is commonly referred to as a tincture and was a well-recognized medical practice at the time.

Dr. Chapman Powell and Mrs. Elizabeth Hardeman Powell

However, Dr. Powell “did not graduate from a regular medical college and is not listed among those granted a license to practice medicine by the Georgia Board of Examiners. He inherited a love for nature and was a natural botanist… and acquired a knowledge of remedies and a cleverness in employing them which justified his claims as a physician.”

Dr. Powell’s practice is described as a forerunner of the Southern Botanico-Medical College, which was established 1839 in Forsyth, Georgia and whose charter would later be transferred to the Georgia College of Eclectic Medicine and Surgery where his grandson would attend.

In all, 16 medical colleges opened and either merged or closed in GA during the end of the 19th century. “Few medical schools existed for more than a few years w/o a major conflict between faculty members. These disagreements were often marked and divisive and public. … The public arguing helped undermine public confidence in medicine and physicians. This attitude was responsible for the demise of many medical schools, with the principals often leaving to start a rival school nearby.” The sole remaining practice is the Medical Department at Emory University in DeKalb County, founded in 1915.

But before we jump ahead into the 20th century important discoveries were being made in the late 1800s. By the time Atlanta was named the state’s capitol in 1877, germ theory had been discovered in Europe and was making its way across the Atlantic. Meanwhile, in the States, the use of every-day alcohols such as whiskey were being employed more and more frequently in medical tinctures and elixirs.

In the next segment of DeKalb’s medical history, we’ll explore medicines such as the poisonous Vapo-Cresolene and Dr. Thacher’s Liver and Blood Syrup.

Sources

“Eclectic Medicine.” Lloyd Library. Accessed September 18, 2020. https://lloydlibrary.org/research/archives/eclectic-medicine/.

North, R L. “Benjamin Rush, MD: Assassin or Beloved Healer?” Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). Baylor Health Care System, January 2000. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1312212/.

“Orthodox Medicine.” Encyclopedia.com, 11 Aug. 2020. Accessed, September 18, 2020. https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/orthodox-medicine.

“What the Doctor Ordered: Dr. Benjamin Rush Responds to Yellow Fever.” Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Accessed September 18, 2020. https://hsp.org/education/unit-plans/diagnosing-and-treating-yellow-fever-in-philadelphia-1793/what-the-doctor-ordered-dr-benjamin-rush-responds-to-yellow-fever.

DHC Archives

Osborne Gibbs, Jeanne. From Cowslip to Cobalt: A Century and a Half of Medicine in DeKalb County, Georgia, 1971. Obj# 975.8.GIBB

DHC Collections

Brass Bleeder Kit Obj# 1981.103.86

Medicinal Whiskey Bottle Obj# 1980.38.1

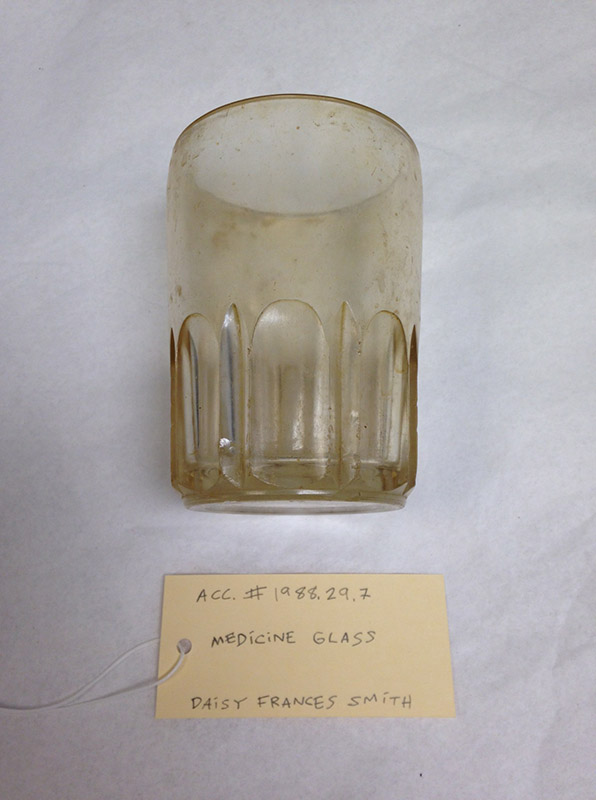

Medicine Glass Obj# 1988.29.7

Quinine Obj# 1981.103.81

DHC Photographs

Chapman Powell Collection Acc# 1985.160.0

Dr. Chapman Powell Home Acc# 1984.280