Benjamin Swanton House and Decatur’s Mid-Century Urban Renewal

Swanton House circa 1890.

History of the Benjamin Swanton House and Decatur’s Mid-Century Urban Renewal

The Swanton House, with a log cabin at its core, is one of the oldest remaining structures in Decatur. The two-room log cabin portion was probably constructed by early DeKalb settler Burwell Johnson and later sold to Ammi Williams. The exact construction date for what is sometimes referred to as “the oldest house in Decatur” cannot actually be determined, but it is estimated to be about 1825. In fact, it is hard to date many early structures in DeKalb County because of a fire in the courthouse in 1842, which destroyed nearly all of DeKalb’s earliest records.

The house was enlarged and updated periodically; each change reflected the popular trends at that time. Over the course of about 100 years, the original pioneer cabin was transformed into a Georgian cottage, which is defined by its floor plan of a central hallway with two rooms on either side. Around 1890, the house was embellished with an Eastlake style porch topped by an addition. The 1890s chamfered wood columns, decorative spandrel, and brackets were replaced by square brick columns in the 1930s to update the porch to the craftsman style; those were retained until the house was moved to 720 W. Trinity Place. The current porch is based on what would have been popular in the 1850s for this type of structure.

Benjamin Franklin Swanton arrived in Georgia from Maine during the 1830s during the Dahlonega Gold Rush to sell mining machinery. He came to Decatur, the seat of government for DeKalb County, and purchased the house in 1852. In the years leading up to the Civil War, Swanton established himself as a successful industrialist who engaged in a variety of businesses, including a brickyard, tannery, and machine shop.

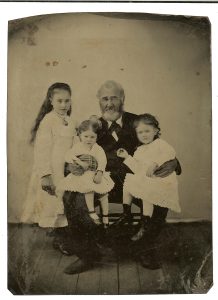

Benjamin Franklin Swanton with grandchildren, (L-R) Sally, Estelle, and Arria, ca. 1875.

During the Civil War, Swanton and some of his family fled temporarily to Maine. On July 19, 1864, the Swanton House became the headquarters for the Federal Army of the Tennessee, who were en route to Atlanta. The Swanton House was spared destruction and remained in the family until 1965.

Inside the Swanton House, 1952. Josephine Swanton Kerr Thompson, reclined in a chair, was the last member of the Swanton family to reside in the home.

The Swanton House on Atlanta Avenue prior to its move, early 1960s.

Concern for saving the Swanton House became public around 1957 when articles about the house and its history were published in The Decatur News. The owners, Mr. and Mrs. Thurman D. Thompson, wanted to move out of the area which had “become commercialized.” Mrs. Thompson was the great-granddaughter of Mr. Swanton and had lived in the house her whole life. The Decatur News editorialized in 1958 that “this old landmark should not be torn down and replaced by a mercantile building. In some manner it should be preserved and possibly used as a Confederate museum.” It should be saved not only for its historical features, “but also because of the tremendous commercial value to Decatur, DeKalb County and the State of Georgia.” At the same time, city officials were already planning to redevelop downtown Decatur by demolishing properties occupied by Decatur’s Black citizens.

Big changes swept the south as the Civil Rights Movement progressed. And in community after community – as if in reaction to these changes – white residents became increasingly interested in saving antebellum houses.

- In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the case of Brown v. Board of Education that the state laws that established separate public schools for Black and white students were unconstitutional. Decatur, like many other Southern towns, built two schools for Black students after this Supreme Court decision: Trinity High School (1955) and Beacon Elementary School (1956). These schools are currently being demolished [in 2014].

- Martin Luther King, Jr., was incarcerated in DeKalb County twice in 1960, in May and October. The second arrest was after a sit-in at the downtown Rich’s located in Atlanta. He was transferred to DeKalb at the request of our District Attorney and went before Judge Oscar Mitchell who sent him to Reidsville.

- Also in May of 1960, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) petitioned the DeKalb County Commission for permission to have a rally or meeting in Decatur at the courthouse (the KKK had previously been denied twice by Decatur in 1951). After denying and then allowing the concept of a meeting by the KKK, the county received letters from local citizens against the Klan. The local radio news also editorialized against the Klan, and the rally was not allowed to occur.

- Superintendent of DeKalb Schools Jim Cherry reported to the DeKalb Real Estate Board in February 1962 that DeKalb’s schools were still segregated. Decatur and DeKalb’s public schools were finally integrated in 1967, although DeKalb was not declared successfully integrated until 1989 by federal courts.

- The March on Washington took place in August 1963, and President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

It is interesting to note that the National Historic Preservation Act was signed into law in 1966. This law was created in part to address the destructive forces of federally funded urban renewal that were occurring in 1960s Decatur: the “urbanization, tear downs, and rebuilding America [which were] destroying the physical evidence of the past.” It is true that in this time period, preservationists were mostly concerned with saving high style architectural buildings closely associated with the well-known white men of history, but since then the movement has grown to acknowledge the importance of everyone’s history.

Decatur’s urban renewal plans were progressing at the same time DeKalb County was developing a low-income housing project in Scottdale, which would later be known as Tobie Grant Manor. Some of the residential land the Decatur Housing Authority sought to acquire would later be used for government buildings, commercial purposes, and the expansion of the Decatur High School. And a new zoning ordinance reduced residential density for new construction. A 1961 report from the DeKalb Housing Authority recommended relocating Beacon Hill residents to Scottdale, but said that of the “211 non-white families now living in the [Beacon Hill] project area,” 90 would not be able to return because there would be fewer residential units after the project was completed.

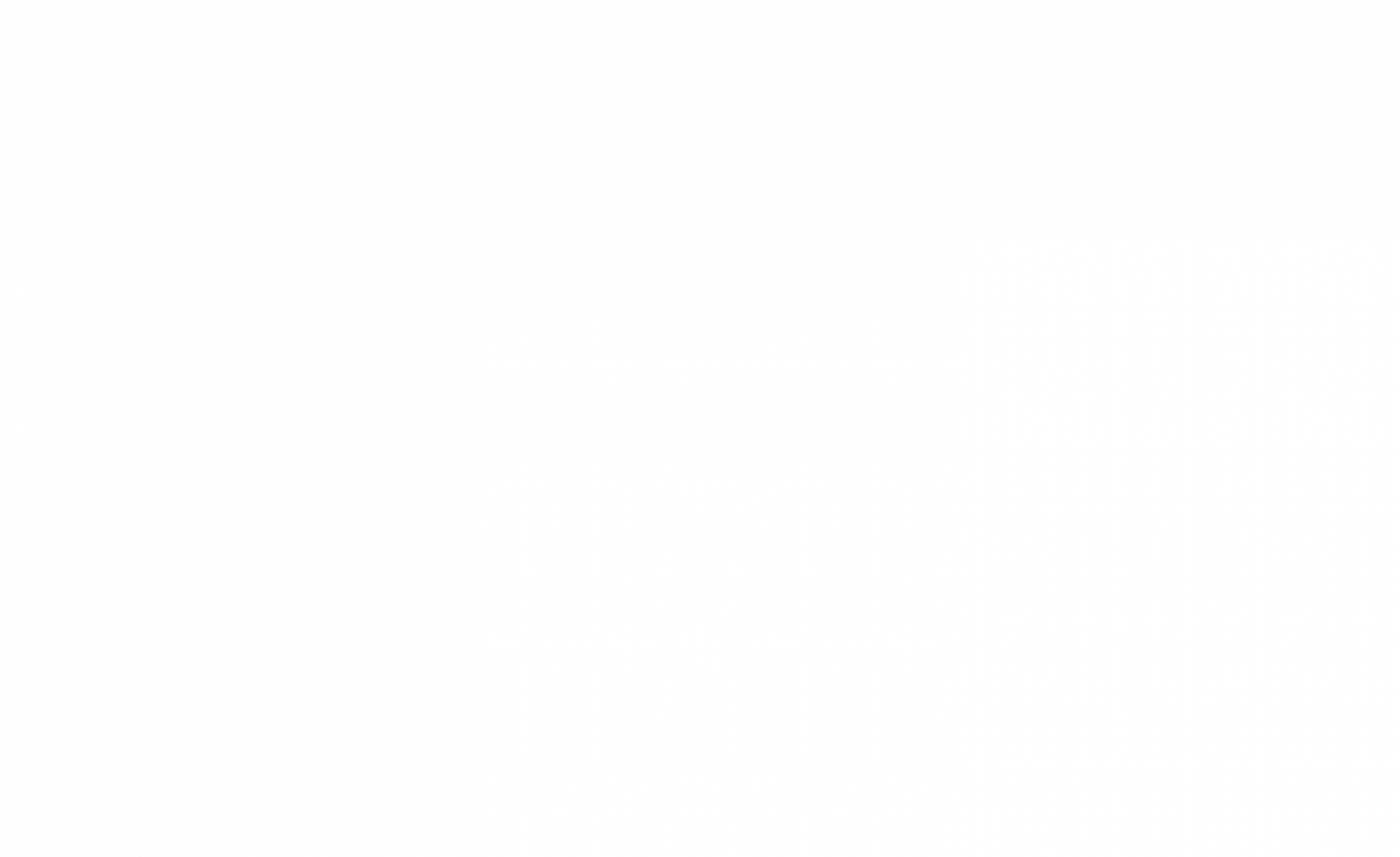

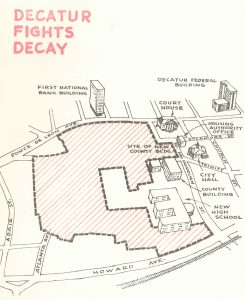

Urban renewal was first used as a development tool in downtown Decatur starting about 1938. It resulted in the loss of many freestanding homes but also the construction of the recently demolished Allen Wilson Apartments (built in 1941). This second round of urban renewal came in the 1960s. In 1957, local newspapers said the Swanton House would be lost due to commercialization of the area, but now they claimed that the house was “threatened by Urban Renewal.” As Decatur’s urban renewal project unfolded, the Swanton House was within the proposed boundaries and it became clear that the same program that threatened it could also save it. This house was seen as a prize jewel that needed to be saved – or removed – from what was called a “blighted area” surrounded by “slums.” Maps produced in 1963 by the City of Decatur for the Housing Authority had marked the Swanton House property as “Not to be Acquired.” The only other property with this designation was the Thankful Baptist Church at 507 Atlanta Avenue. The urban renewal project drastically changed a number of Decatur’s streets and by 1970 had effectively removed car access to Thankful Baptist Church from the Black community that built it. But the congregation at Thankful Baptist had no time to figure out alternatives before the building was destroyed by an unexplained fire on September 23, 1970.

In 1964, the DeKalb New Era reported that the Swanton House would not only “escape destruction in Decatur’s urban renewal program but likely attain the status of a full-scale shrine [emphasis added].” The owner sold her property to the Decatur Housing Authority in January of 1965, with a right to reserve the historic structure, which was appraised as having no value. But by then, Mills B. Lane, Jr., president of C&S Bank, was already interested in the house: his plan was to restore it on-site or move it to land owned by the City of Decatur. Our 1970 file notes state that he purchased “the house itself from Mrs. Thurman Thompson” and had an option “to purchase the entire block [of land] from the City of Decatur through the Housing Authority.”

After considering his options to either restore the house on-site or move it, Lane made the decision in 1970 to move it and provide funds for its restoration to the DeKalb History Center if the city would provide land. Much of the urban renewal project had been completed. “Slum” housing and commercial businesses surrounding the Swanton House had been demolished. The street we know as Commerce Drive had been carved through downtown and included the one block of Oliver Street, named after Black business owner Henry Oliver. The street was renamed in 1983 disregarding the historical origin of its name. The street around the Swanton House (Atlanta Avenue) became curved and would eventually be named Swanton Way. And Atlanta Avenue no longer led travelers from Decatur to Atlanta – a few unconnected blocks were all that remained.

This article was originally published in our print newsletter, Times of DeKalb, in the Spring of 2014. It has been edited for clarity and with additional information.

Part 2 picks up with preservation efforts to keep this cornerstone piece of DeKalb’s history.

______________________________