Dry DeKalb: Prohibition and Temperance in DeKalb County

Read the history of prohibition and temperance in DeKalb County.

By Kathryn Turnbull, Archives Assistant

If you’re meeting up with a friend or two for a drink (or two), agreeing on which of DeKalb’s 2,000+ bars, restaurants, and breweries to go to might be a challenge. But that hasn’t always been the case—a century ago, DeKalb, like the rest of Georgia and the United States, was (legally) dry, and the business of serving, brewing, distilling, and wholesaling alcohol looked very different than it does today.

On June 26, 1918, Georgia became the thirteenth state to ratify the Eighteenth Amendment. Yet Georgia was already “bone-dry” when the amendment was introduced. “Georgia Now ‘Dryest’ State in Country,” “All Liquor Depots in Georgia Closed,” and “’Bone-Dry’ Bill Signed Last Night and Became Law of State At Once” covered the front page of The Atlanta Constitution the day a brand new prohibition law took effect on March 29, 1917. The bill had been rushed through the state legislature on the 28th, with a vote in support from Rep. Smith of DeKalb County, and was signed just before midnight by Governor Nathaniel Harris. Today, the pace at which the “bone-dry” bill became law might seem extreme, moving from the legislature to the governor’s desk in a matter of hours and taking effect the very next day. For many Georgians, however, prohibition at the state and national level during the early twentieth century was not a completely shocking development. (Smith & Boyle, 113) Indeed, temperance and prohibition movements had been influencing public policy and social attitudes against alcohol for decades, in Georgia and across the country.

Illustration from The Atlanta Constitution, November 11, 1918 via Newspapers.com.

The temperance movement was one of the most well-supported progressive movements of the nineteenth century. DeKalb County had had its fair share of temperance societies and prohibition-minded organizations since the county’s establishment in 1822. One of the first such documented groups was a local chapter of the Washingtonian Society. Originally founded in 1840, the Washingtonians were a Baltimore-based temperance organization that seems to have functioned similarly to the modern Alcoholics Anonymous; working-and-middle-class men concerned by their alcohol use came together for regular meetings to support one another in total abstinence from alcohol. (O’Neill, Westport Historical Society) Unlike many other organizations within the temperance movement that were closely affiliated with the church, the Washingtonians were decidedly independent from religion, leading to their ostracization by ministers and other temperance groups. According to George W. Yarbrough’s 1917 book, Boyhood and Other Days in Georgia, Decatur’s own Washingtonians held monthly rallies at the Courthouse on Fridays throughout the 1840s, presided over by Judge William Ezzard. Yarbrough recalled,

“These were great temperance times, and the old courthouse was the rallying place [. . .] They were stirring occasions – powerful speaking, and earnest exhortations to sign the pledge. In those days Decatur was not ‘wet,’ but a little damp, particularly during court weeks, militia muster days, and Fourth of July. I never saw a resident of Decatur drunk on the streets. Some took their drams regularly, but they did it as gentlemanly as the thing could be done.” (Price, 268)

Decatur’s Washingtonians may have rallied at the third DeKalb County Courthouse (1847-1898). photo from DHC Collections.

Crime, especially in urban settings, was easily attributed to the “evil” influence of alcohol as well as poor public education, and DeKalb was not immune. Beginning as early as 1852, a DeKalb Grand Jury was formed in response to “an alarming increase of crime in our county, and is casting about for the cause.” After indicting citizens for operating a “tippling house,” or bar, “on the Sabbath day,” selling liquor to several enslaved men, and “selling liquor without a license,” the Grand Jury issued their recommendations for implementing a public education system in addition to enacting a local prohibition law. “We are therefore of the opinion,” the statement declared, “that no plan which has been suggested for the suppression of this evil can be looked into with any hope of success which stops short of an absolute prohibition of the retail [sale] of intoxicating drinks.” (Price, 306) DeKalb County would not be officially dry until November 19, 1885, when the last bar in Stone Mountain closed its doors for good. “There is now no whiskey sold in De Kalb County [sic],” announced the DeKalb Chronicle. (Garrett, 98) Fulton County and the City of Atlanta would vote for and achieve total prohibition until the following year.

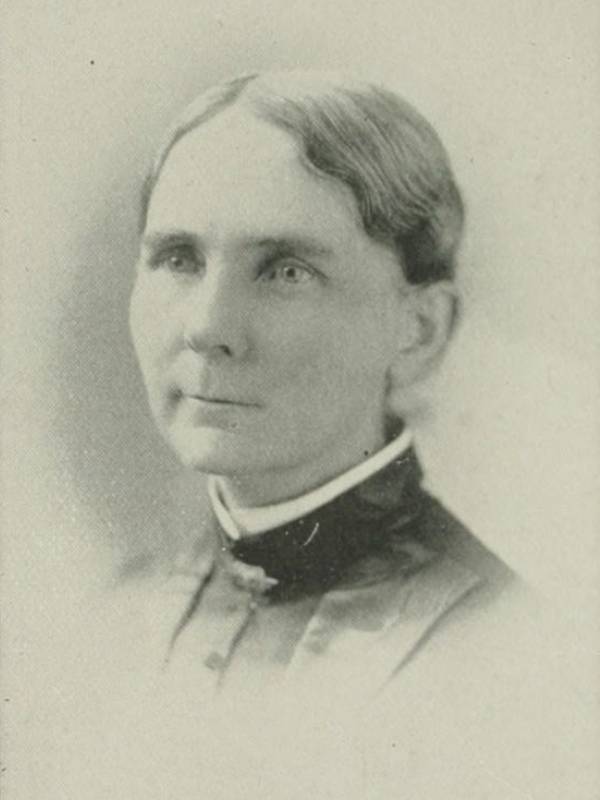

The Washingtonians’ influence over Decatur seems to have fizzled out fairly quickly, disappearing entirely from the record by the mid 1850s. A handful of other organizations sprung up throughout the mid nineteenth century, including the Sons of Temperance, the Anti-Saloon League, the American Temperance Union, and the National Prohibition Party, but perhaps the most notable locally was the Georgia Women’s Christian Temperance Union (or WCTU), a state chapter of the national organization. Officially organized in 1883, DeKalb citizens like Rebecca Latimer Felton, Mary Harris Gay, and Missouri Horton Stokes (Gay’s half-sister) became early influential leaders of the Georgia WCTU, taking up the work of organizing parades, lobbying at the local and state level, distributing literature, and conducting meetings. Nationally, the WCTU quickly gained prominence and would become the largest women’s organization in the country by 1890. The WCTU advocated for the total prohibition of alcohol, slowly expanding the organization’s issues of interest to include women’s suffrage, labor rights, public health, and other progressive issues of the day.

Missouri Horton Stokes, revered Secretary of the Georgia WCTU and native of Decatur.

Photo from Woman of the Century by Charles W. Moulton, public domain.

Like other temperance organizations of the day, the WCTU’s messaging was highly moralistic; alcohol consumption was identified as the most egregious and needless cause of poverty, disease, hopelessness, pain, and misery. The women of the WCTU “dreamed of a state redeemed from the oppression of the liquor traffic; they dreamed of homes to which domestic happiness and prosperity were restored; [. . .] oh what glorious dreams they were!” declared Theresa Griffin in the introduction to the Georgia WCTU’s own organizational history, self-published in 1914. The WCTU detested the culture which brewed within the saloon, the barroom, and the “hated dram-shops,” where upstanding Christian heads of households were stripped of their dignity and sense. Given their deep concern over criminality and the organization’s origins in the post-Reconstruction South, it might not be surprising that proponents of the all-white Georgia WCTU and the Georgia temperance movement more broadly were also outspoken advocates of Lost Cause ideology, segregation, and defenders of racial terror. Amidst the social turbulence of the 1890s, Decatur-born Rebecca Latimer Felton accused Atlanta’s anti-Prohibitionists, or “Wets,” of attempting to buy the Black vote with alcohol. One quote from a 1897 address by Felton would become infamous: “If it takes lynching to protect women’s dearest possession from drunken, ravening human beasts, then I say lynch a thousand a week.” (History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives) Felton and other WCTU members linked preexisting stereotypes about violent, hypersexual Black men with the movement for prohibition in order to gain support for their cause at the cost of Black Americans’ safety and humanity. Consider the 1906 Atlanta Massacre and its connection to alcohol—Decatur Street’s Black-owned bars (and any bars that dared to serve Black patrons) were targeted specifically. Time and time again, proponents of prohibition shamelessly used racial tensions and stereotypes to their advantage in their crusade against alcohol. Immediately after the massacre, a white preacher named Sam P. Jones testified at a revival in Cartersville:

“Liquor was behind all those atrocious deeds committed by the blacks in and around Atlanta [. . .] you may say that the bloodshed in Atlanta last night was inevitable, but whiskey, yes, whiskey, was behind it. I want to see those disgraceful Decatur Street dives of debauchery and sin obliterated.” (Newman & Crunk, 461-462)

Though much less well-known than the 1906 Massacre, a violent event in Decatur in August 1887 exemplified the racial motivations of temperance next-door, in DeKalb County. On August 27, African Americans in Decatur were celebrating the anniversary of the Negro Sunday Schools of DeKalb County “with whisky and pistols.” Hearing that the party was in full swing and that “the whiskey was flowing,” the town bailiff, town Marshall, and three other white men stopped by, ostensibly to merely observe the celebration. According to The Atlanta Constitution’s report, several Black men who were celebrating came outside to ask the bailiff to arrest a man inside who was drunk and “brandishing a pistol over his head,” causing others distress. When the bailiff attempted to arrest the drunken man, a gun fight broke out between three Black men and four of the White men, during which one of the White men was killed and another was wounded. The White man who was killed was the Marshall, J. F. “Tobe” Hurst. The “several” unnamed Black men who were arrested had to be quickly transported to Fulton County “for safekeeping” when rumors began to spread about a lynch mob forming in Stone Mountain. (Garrett, 133)

I could find no further information regarding the names, safety, punishment, or futures of the arrested Black men, nor about the mob at Stone Mountain, the city which would bear witness to the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan less than 30 years later. Furthermore, many historians have pointed out how national Prohibition under the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act heralded a new era for the KKK, during which the Klan enticed “millions of Protestant white evangelical Americans into its ranks” under the guise of becoming a vigilante militia for prohibition enforcement. (Little, “How Prohibition. . .”) Though they may not have seen eye to eye on all social issues, the WCTU and the KKK sought to uphold racial power dynamics, villainize alcohol consumption, and promote a brand of white Christian nationalism.

Ironically, the women of the WCTU may have imbibed regularly, if unknowingly. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, so-called patent medicines were popular tonics marketed to solve an array of discomforts, anxieties, and other “womanly troubles.” Yet, as Ron Smith and Mary O. Boyle point out in Prohibition in Atlanta, “many temperate women were shocked when the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 revealed that many of their regular patent medications contained as much as 22 percent or more alcohol by volume, along with substances such as morphine, opium and cocaine. A 1904 survey reported that 75 percent of the WTCU members polled regularly took patent medicines.” (Smith & Boyle, 97) Since these “medications” were so popular among WTCU members, it’s very possible that DeKalb’s most outspoken temperate women, including Gay, Felton, and Stokes, also turned to such remedies without knowing their true contents. Even if they were only ever consumed in small doses, one wonders how much of the relief advertised was due to the potent, “patented” blend of alcohol and other addictive substances within. A WCTU woman “feeling better” after self-medicating with a patent medicine “was not necessarily the result of patent medicine’s medicinal properties; but rather related to the fact that many patent medicines were laced with opiate drugs and alcohol.” (Bahnemann, Digital Public Library of America) Examples like this also illustrate how the era’s medical knowledge differs from ours today, illuminating the irony in how the temperance movement failed to attend to addiction to opiates in their focus on alcohol alone.

Beginning January 17, 1920, national Prohibition would dramatically change the landscape and culture of American alcohol consumption. Forced underground or out of business by official federal enforcement agents and volunteer terror organizations like the KKK, DeKalb brewers, distillers, wholesalers, and retailers would not be able to legally produce or sell any beverage alcohol until 1938, when the Georgia Legislature voted to return to a local option model, where individual counties would vote on local liquor laws. (Smith & Boyle, 148) While 12 counties remain partially dry to this day, DeKalb residents have no shortage of options when it comes to finding a good drink. Whether or not you choose to observe “Dry January” this year, reflecting on DeKalb’s complicated relationship with temperance and prohibition might make you glad that you get to choose at all!

Works Cited:

Ansley, Lula Barnes and M. Theresa Griffin. History of the Georgia Women’s Christian Temperance Union from Its Organization, 1883-1907. Columbus, GA: Gilbert Printing Co, 1914. Digitized by the University of Georgia. https://dlg.usg.edu/record/dlg_zlgb_gb0451

The Atlanta Constitution, March 29, 1917. https://ajc.newspapers.com/image/34214902/?terms=

Bahnemann, Greta. Quack Cures and Self-Remedies: Patent Medicine. Digital Public Library of America. September 2015. https://dp.la/exhibitions/patent-medicine

Garrett, Franklin M. Atlanta and Environs: A Chronicle of Its People and Events, Vol II. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1954, and Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1969.

Little, Becky. “How Prohibition Fueled the Rise of the Klu Klux Klan.” History.com. The History Channel, January 15, 2019. https://www.history.com/news/kkk-terror-during-prohibition

Newman, Harvey K. and Glenda Crunk. “Religious Leaders in the Aftermath of Atlanta’s 1906 Race Riot.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 92, no. 4 (Winter 2008): 460-485. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4058508

O’Neill, Jenny. “The Washingtonians and the Nineteenth-Century Temperance Movement in Westport.” Blog of the Westport Historical Society, June 16 2010. https://wpthistory.org/2010/06/the_washingtoni/

Price, Vivian. The History of DeKalb County, Georgia, 1822-1900. Fernandina Beach, FL: Wolfe Publishing Company & The DeKalb Historical Society, 1997.

Rebecca Latimer Felton Biography. History, Art & Archives of the United States House of Representatives. https://history.house.gov/People/Listing/F/FELTON,-Rebecca-Latimer-(F000069)/

Smith, Ron, and Mary O. Boyle. Prohibition in Atlanta: Temperance, Tiger Kings & White Lightning. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2015.

Yarbrough, George Wesley. Boyhood and Other Days in Georgia. Nashville: Publishing House of the M.E. Church, South, 1917. Digitized by the University of Georgia. https://dlg.usg.edu/record/dlg_zlgb_gb0303