Contemporary Living, Northwoods

The Northwoods neighborhood in Doraville brought modern contemporary living to DeKalb’s young middle class families.

Originally written by Rebecca Crawford, 2010

Updated by Marissa Howard, 2022

The “Ranch House Initiative” was developed in 2009 by the DeKalb History Center and DeKalb Commissioner Jeff Rader in an effort to understand the ranch house boom that occurred in nearly every part of DeKalb County throughout the mid- to late-20th century. Perhaps the ever present ranch house might seem like an odd project for us to research. Why focus on something as ubiquitous and ordinary as a ranch house? Simply stated, houses make up more than three-quarters of our built environment, and they are key in understanding social and cultural phenomena. By studying the single-family home, it is possible to take an up-close and personal view of the family that lives inside, as well as the surrounding community. Although it might seem that the ranch is unpretentious in character, by examining both the interior and exterior, we can gather a great deal of information about mid-century America and specifically DeKalb County. As architectural historian Richard Cloues explained, the “mid-century house has mid-century stories to tell.”

Our goal was to look at a variety of different ranch neighborhoods throughout the county. The original initiative profiled four neighborhoods which ranged from high style modern houses designed by notable architects (Briarpark Court), to the simpler but widespread traditional red brick ranch developments. Two of the neighborhoods were large planned communities (Northwoods and Belvedere Park), while the last shows how family farms were slowly sold off and developed, piece by piece (Sargent Hills). Through this and ongoing research, we show how the ever-present ranch house is an important piece of understanding the history and development of DeKalb County in the mid-20th century.

Note: Information on the other neighborhoods mentioned above will soon be posted to our blog. After the DHC completed our Ranch House Initiative, a graduate class of Georgia State University’s Heritage Preservation Program, created a context document with a wealth of detail about Single-Family Residential Development, DeKalb County, Georgia, 1945-1970. Then in 2013, the DeKalb History Center opened our exhibit The Mid-Century Ranch House: Hip and Historic!

Northwoods + Doraville

This article is dedicated to Bob Kelley (1951-2022), longtime Doraville historian and Northwoods resident.

Although there are conflicting accounts of how Doraville came to be named, perhaps the most popular explanation is that the town was named for Dora Jack, whose father was an official for the Atlanta and Charlotte Air Line Railroad (which eventually became the Southern Railroad). In an effort by church leaders to control two saloons that had opened in the area, Doraville was incorporated by the General Assembly on December 15, 1871. The railroad depot (where the MARTA station is currently located) was the center of town, and the boundary-lines extended from the depot to one-half mile in every direction.

According to the 1900 census, Doraville was home to about 114 people: there were 25 families and 23 dwellings. At the turn of the century, downtown consisted of a jail, three stores, a corn mill, barbershop (open only on Saturdays), a post office, doctor’s office, and a church. The main road was New Peachtree Road, formerly called Main Street, and it stretched from downtown Atlanta’s Five Points, through Doraville, and on to Pinckneyville.

During World War I, Chamblee – the town next to Doraville – was transformed from corn fields into one of the largest cantonment areas in the country, Camp Gordon. Built in 1917, 30,000 army recruits were trained at Camp Gordon, and small town Doraville felt the effects of the densely populated Chamblee. But the effect was short-lived as the base was closed after the end of the war. World War II also had a strong impact on Chamblee and Doraville, as the area that had formerly been occupied by Camp Gordon was transformed into the Lawson General Hospital and the Naval Air Station. This area became DeKalb-Peachtree Airport in 1959.

During the 1930s, severe economic depression led to the closing of the Southern Railway’s Doraville depot. Although there were efforts to reopen the depot in the 1940s, it was eventually demolished to make way for the MARTA station. By the end of the 1930s, Doraville and surrounding areas were considered to be an economic wasteland. The town struggled to survive as Georgia’s economy transformed from agricultural to industrial. Doraville’s seemingly grim fate changed when Scott Candler proposed a new $1,000,000 water plant to be built in Doraville.

The landscape of Doraville was forever altered when the Scott Candler Filter Plant was completed in 1942. In the early 1940s, General Motors began surveying the suburbs of Atlanta to find an appropriate location for their new plant. Doraville’s newly built water main was 30 inches in diameter, which overshadowed other towns which typically had 12 inch water mains.

Scott Candler was able to woo General Motors into choosing Doraville for their new plant in Georgia. By 1945, the deal was closed and the corporation began sorting out the logistics of their newest endeavor. Yet, before the arrival of GM, there were several smaller industrial companies that made their homes in Doraville. The Plantation Pipeline Company opened a facility in 1942, and suddenly there were thousands of tanks stored in Doraville tank farms. Shell Oil Company, Standard Oil, and American Oil Company staked out sectors of Doraville in which they could store gasoline, oil, and kerosene which would then be exported to various regions. By 1949, Candler’s water system had brought seventy-five million worth of industrial development to north DeKalb.

Construction of the GM plant commenced on land purchased from African American residents of Doraville. For $171,667, the corporation purchased 408 acres from 50 different landowners. But the Doraville City Council refused to rezone that acreage unless GM found a place for these displaced residents to live. The result was Carver Hills (1949), a 150-acre subdivision where individual lots were sold to the displaced for $2,000. Named after George Washington Carver, this new and intentionally segregated neighborhood had “up-to-date amenities” such as water, electricity, and paved streets. Almost nothing remains of the community of Carver Hills – the portion north of I-285 has been entirely replaced by townhomes. The population in and around Doraville grew as other subdivisions were built close to the factory, including Guilford Village which was constructed on 58 acres near Tilly Mill and Flowers Roads.

GM needed additional infrastructure to support materials coming into the plant and the completed new cars leaving the plant. In a state and federal partnership, Peachtree Industrial Boulevard was created in 1947 to serve this need and it opened concurrently with GM’s plant. The new state highway also accommodated workers on their commute to and from the plant. At four lanes and $803,000, Peachtree Industrial was more than $100,000 over the projected cost. At the end of 1947, the plant had completed production of 350 cars. That number would jump to over 29,000 the following year.

Northwoods

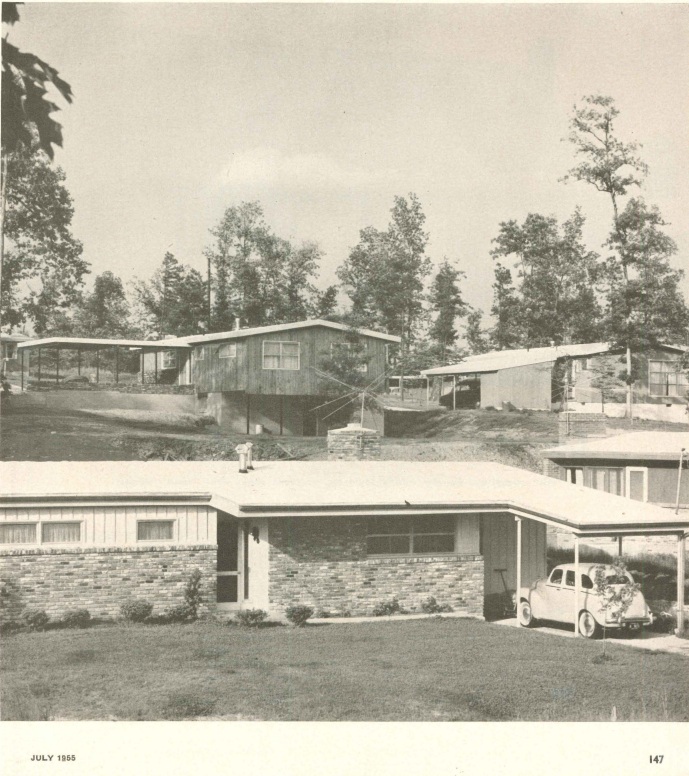

Northwoods homes featured in House and Home, July 1955.

In 1949, Doraville’s growing population was ready for a residential development composed of middle-class, single-family homes. Atlanta developer Walter Tally envisioned a community that he named Northwoods, as one that would serve as a magnet for young families eager to take advantage of DeKalb’s amenities. Located only 11 miles from Atlanta via Buford Highway, Northwoods grew steadily over nearly a decade. Between 1950 and 1959, 700 new homes were constructed on 250 acres of land bounded by Shallowford Road, Buford Highway, and Addison Drive. Northwoods differed from similar developments because it was more than a residential neighborhood. Tally’s vision not only included single family homes, but also a community which had new schools, churches, a professional building, and a shopping center.

It was in the wake of the post World War II housing boom that the ground broke to build the first homes in Northwoods. Now located in the southwestern portion of the development, these early homes were conventional looking ranches with hipped roofs; the designs were found in plan books or were purchased from a publication such as Home Builder’s Plan Service.

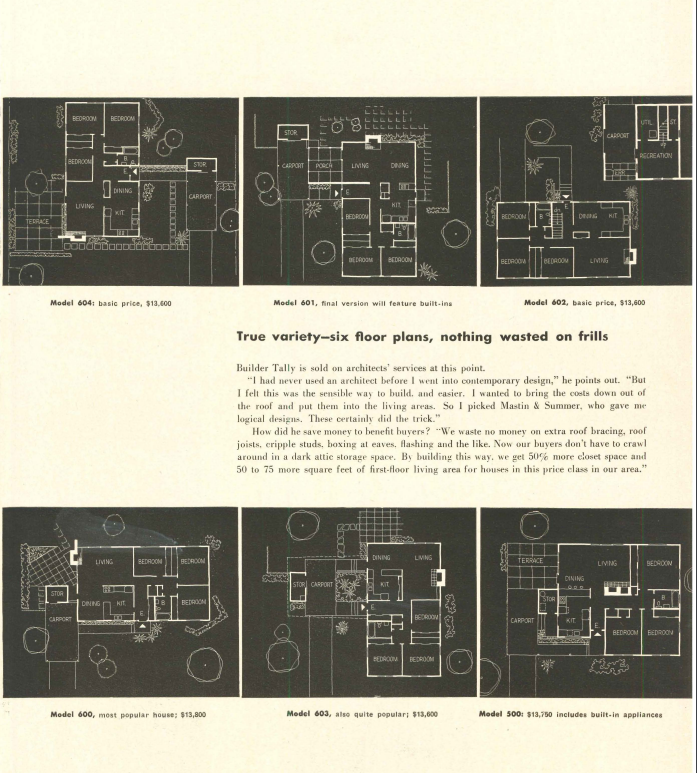

In 1953, as the sale of the traditional ranch homes began to slow, Tally decided to change his development strategy. He brought in young Georgia Tech trained architects Earnest Mastin and John Summers, who infused their designs with innovation, while still keeping prices down. Buyers could choose from six different floor plans that Mastin and Summers had designed, and each lot had its own septic tank and included just enough space for the home and an attached carport. The homes had one bathroom, and were not equipped with air conditioning. The flat roofs prevented the homes from having attics with duct work, and the architects used radiant heat from the floor instead.

“True variety-six floor plans, nothing wasted on frills.” Mastin and Summer’s six floor plans for Northwoods. House and Home Magazine, July 1955.

“Now our buyers don’t have to crawl around in a dark attic storage space. By building this way, we get 50% more closet space and 50 to 75 more square feet of first-floor living area for houses in this price class in our area.”- Walter L. Tally, House and Home, July 1955.

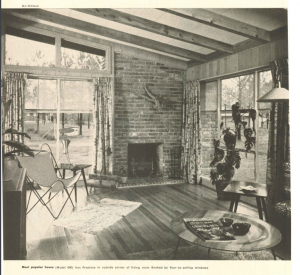

Open floor plans were an essential element of the Mastin and Summer designs. In these contemporary houses, kitchens were no longer relegated to the rear of the home; they became an important area for the family. Homes in Northwoods were equipped with the most up-to-date amenities like dishwashers and disposals, and there was less emphasis on formal entertaining. For some families it became commonplace to eat in the kitchen. The architects’ designs also included wood burning fireplaces, an amenity that was usually not available in homes within Northwoods price range.

Model 600 features a built in fireplace. These homes were featured in the magazine House and Home, July 1955.

The architects were able to adapt their plans to Peachtree Ridge’s hilly topography by also designing split level homes, which easily accommodated sloping lots. Mastin and Summers’ designs emphasized the importance of nature and the outdoors, and many models featured outdoor patios and barbecues. The architects used sliding glass doors and jalousie windows, which were modern products. Floor to ceiling windows helped to blend the indoors of the homes with their surrounding natural environment.

- Addison Drive

- Allison Drive

- Chesnut Drive

- Raymond Drive

- Addison Drive

Walter Tally, who would later develop the Northcrest, Sexton Woods, Brookvalley, and Brittany subdivisions, worked with Mastin and Summers to develop ways to keep the cost of the homes low, while still making them desirable to young couples. Tally appealed to homebuyers, because he would let them choose the lots they wanted. Potential residents could also meet with Mastin and Summers to customize their homes, which was a savvy sales tactic that made the buyers feel as though they were getting a custom home at a bargain price. Early Northwoods residents included the architects (Mastin and Summer each purchased a home in the community), engineers, and employees of Lockhead, General Motors, and Delta.