True Crime-Margaret Burton aka Mrs. Gray

The wild story of crime, embezzlement, and 22 aliases. The story of Mrs. Gray, True-crime in Decatur.

Originally Posted: May 2019

Updated: Jan 2022 with additional images and information.

_______________________

It seemed like a strange place for a crime. A small, sleepy town of under 20,000 people, Decatur was a backwater in comparison to its larger, glamorous, bustling cousin, Atlanta. Yet, soon, the events set in motion here would be the talk of the nation.

It all began with one woman. Tall, older and stately, but with a youthful face unburdened by wrinkles, she automatically stood out of the crowd. Her cascade of silver hair made her appear glamorous if slightly cold. She cut a stylish figure, ensconced in the wide, oversized, flouncy skirts of the 1950’s. She was respectable and classy.

Yet, don’t be fooled, appearances can deceive you.

Many were drawn in by her. She spun stories deftly, like a spider deftly weaving her web. Her father was the former President of Panama. She owned mining interests out in Colorado. Her husband, a former colonel, had died. All of these factors served to make her independently wealthy, fitting into the respectability politics for a woman. Additionally, it provided an explanation for her extravagant spending. She seemingly had it all: stylish clothes, a multi-acre home, and numerous show dogs.

She arrived in Decatur in 1954 and quickly set her sights on a Decatur Medical Clinic. Though it was a modest but handsome brick building, by the 1950’s, business was booming. Seven doctors were on staff with five visiting specialists, and, short of major surgery, most medical procedures could be performed within the office. Cash was flowing and the times were good.

Though she was well-off, Mrs. Janet R. Gray applied for the office manager job. She loved a good challenge and claimed that the job would keep her mind occupied. In return for her services, she received $400 per month. This was a generous salary, exceeding that of many male officers workers at the time. The doctors at the clinic liked her immediately: she was self-assured, possessed an air of refinement, and, strangely, bandied complex medical terminology about with casual ease. Under her, the clinic appeared to run smoothly.

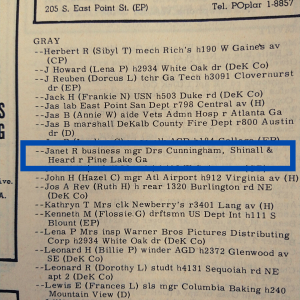

1956 Suburban DeKalb Directory. Note her residence is listed as “Pine Lake, Ga”. We don’t know if this was her “second home”, as some reports suggested she had multiple homes. Her well known residence at the time was on Happy Hollow Road in Dunwoody.

The doctors were unaware of the developing underlying tensions. The administrative staff strongly disliked their new boss. Mrs. Gray was a stern and demanding supervisor. She pushed those under her purview to work hard, but did not put in a similar effort. Carole Whitney, a University of Georgia co-ed, who worked at the clinic in 1956 noted that “More often than not Mrs. Gray would come in the morning, leave at 10 or 11 [AM] and return later in the afternoon.”

Some found her to be tyrannical. Morale was low, and workers quit due to their inability to secure a raise. Mrs. Shelnutt, a clerk at the clinic, claimed that she was forced to work overtime by several hours per day but was not properly compensated.

“Mrs. Gray “would demand that I stay there and pound her fist on the desk at me… We were at the disposal of Mrs. Gray and whatever she told us we had to do.”

Ora Shelnutt, Clerk

Employees were also disconcerted by the haphazard business practices in the clinic. The cash and receipts for the day, which often totaled over $600, were left in an unlocked drawer. This meant that employees had easy access to the money, though someone was always present, in the seat or by the desk. This made clerks nervous: Mrs Henderson noted that this kept her in a state of anxiety: she “didn’t like being held responsible for cash that other persons had their hands in.”

This sense of suspicion was transferred to Mrs. Gray. Employees began watching her. Mrs. Whitney once saw her leave with the cash receipts in her brown briefcase. June Thurmond, another clerk, thought that it was strange that Mrs. Gray solicited delinquent payments. When Mrs. Gray did so, she used a nome de plume, J.M Royer. Queerer yet, when Thurmond balanced the receipts against payments received, she noticed that the total was off. Mrs. Gray would not let her check the adding machine records to rectify the discrepancy.

Furthermore, Mrs. Gray’s control over money extended to the deposit safe. One night Mrs. Thurmond made the mistake of locking the filing cabinet safe. The next morning, it could not be opened as no one knew the combination. Apparently, Mrs. Gray typically locked the drawer overnight and only she had the key. Despite the many irregularities, the staff excused them. Mrs Gray was the bookkeeper, a competent office worker, wasn’t she?

The interior of Mrs. Gray’s Happy Hollow living room. The room had a “peaked cathedral ceiling” with Empire and Victorian love-seats. With the abundant light, one writer described it as comfortable, lived-in country house with lavish decorations, including a room full of jade figurines (Atlanta Journal Constitution)

A hallway with luxurious wood siding. The Renaissance cabinet on the left cost more than $600, more than a month’s salary. One onlooker said that she “wouldn’t pay more than a nickel for a truckload,” illustrating how relative taste is (Atlanta Constitution)

On a tour of Mrs. Gray’s home, Peggy and Mrs. R.R Patillo try one of the hats on Mrs. W.C Patillo (Atlanta Constitution)

During the interim years, Mrs. Gray’s social reputation grew rapidly. Her wealth guaranteed her access to the upper echelon of Atlanta society. She looked the part too, stylishly attired. Her wardrobe was extensive, and she owned over fifty hats and 113 dresses alone. She was addicted to luxury: dogs, fine cars, and fur coats, she tolerated only the best.

In five years she bought five cars; two Lincolns, a Mercury, a Pontiac, and a flaming red MG. This was in addition to her 1953 air conditioned Chrysler.

Her house was similarly lavish. She lived on fifteen acres on Hollow Hills Road, what was then rural DeKalb County. Her house had seven rooms and a pool which allowed her to throw “sumptuous and gay” parties. It was furnished with fine French and Italian antiques.

The home, originally called “Happy Hollow”, was the summer home to several prominent families. You can read the history of the home here.

Mrs. Gray worked hard to preserve the veneer of wealth, even with those who surrounded her. Her niece, Candace Victoria Laine, was the daughter of a countess. She attended the prestigious Atlanta private school of Westminster, whose name served as a password into elite circles.

Rise and Shine, one of Mrs. Gray’s more than 50 cocker spaniels, wins Best In Show in 1954 at the Westminster Dog Show (Westminster Dog Show)

Most importantly, she became a influential dog fancier. Her cocker spaniel, Rise and Shine, won the Westminster Dog Show in 1956, and was considered one of the best living examples of the breed. Spaniels were her passion project: she had more than fifty. From these dogs, she started Gala Kennels which was well regarded. She also had a flair for unique names. What is better for a dog than Piccolo Pete and best of all, Capital Gains?

Though the clinic was growing, the doctors were concerned by their declining gross income; thus, the clinic hired a new accountant, John C. Walsh. Moving forward, Mrs. Gray was demoted to being Mr. Walsh’s assistant. Yet, this was to be her downfall.

On July 30, 1957, Mrs. Gray got a fateful telephone call. The clinic discovered a shortage of cash. They asked her would she be available to come in and explain the discrepancy? By all appearances, the doctors seemed to be in disbelief, thinking that she was blameless. Mrs. Gray who was away “on a weekend trip to Florida” would be happy to come in and explain that Monday. When she did not come into the office, worried coworkers visited her Happy Hollow home. What they found were doors open, furniture gone and a phone off the hook.

Mrs. Gray’s almost three years in Decatur were an elaborate fabrication. Her name was not Janet R. Gray; in truth, she was Mrs. Margaret Lydia Burton, a British citizen born in Tientsin, China in 1906. She had a long history of embezzlement spanning over eighteen years in America, beginning in 1939 in Honolulu where she was working for a local Chinese rug company. She had committed crimes in three countries, four additional states and had over twenty-three aliases. During her thirty-one months at the clinic, Mrs. Burton allegedly stole $100,000 and that number would continue to rise as more details came to be known.

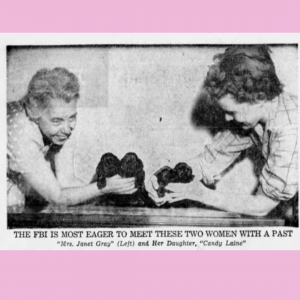

Most shocking, her ‘niece,’ Candy, was, in truth, her twenty year old daughter, Sheila Joy Burton. Sheila had posed as a fifteen-year-old student, at Westminster. Candy Laine was reportedly, “buxom” and an honor student with a high IQ. She herself had over nine aliases, and authorities were unsure about her complicity. Her mother’s crime spree had begun when she was eighteen months. What else could she do? This was her habitat; whenever things got sticky for her, she would pack up and leave. America was an easy country to vanish within. She could create a new past and identity for herself easily. She would commit a crime, rinse and repeat.

Mrs. Burton slipped away easy. She gave away ten of her dogs to local friends. She packed up remaining thirty-eight dogs and personal belongings of her Happy Hollow home into a caravan of cars, driving throughout the night Greensboro, North Carolina. She led the charge in her pink sedan, followed by her ‘niece’ in a station wagon and was followed by two vans with hired drivers. Her employer, concerned about her When the vehicles became too conspicuous, she abandoned them in Greensville, South Carolina. The dogs (with the exception of three prominent prize-winning dogs: Rise and Shine, Piccolo Pete and, ironically, Capital Gains) were transferred over to her dog trainer, Ted Young Junior, who took them back to Connecticut (He later faced charges for criminal conspiracy). After that, the FBI lost track of Mrs. Burton. She drove off with her daughter in a Pontiac and went unnoticed through one police checkpoint after another.

The case of Mrs. Gray was carried widely, ranging from Connecticut, Indianapolis, Arizona, New York, Ohio, Missouri, Texas, Michigan, and even internationally in Hong Kong. These stories often emphasized her exotic nature. The Hartford Courant labeled her as an “international adventurer.”

Much of the fascination can be traced to the ways in which Mrs. Burton both transgressed and fit within normative gender values of the 1950’s. On a surface level, she was a perfect woman: she possessed feminine charm and had a classic elegance, she could entertain guests while being a mother. She was also a kind of Marion Crane-esque figure: she committed a lengthy crime spree and was a divorcee. It was difficult to categorize her and this dichotomy fascinated the public.

Former friends of ‘Mrs. Gray’ were in total shock, especially members of the Cocker Spaniel Club, who had recently begun to nominate her as the Southeastern Representative. Mr. and Mrs. Estes, close friends of ‘Mrs. Gray,’ described how they were shaken, comparing it to “picking up the paper and reading that President Eisenhower was a communist.” Initially, they did not believe the charges levied and they had planned to aide her. Now, they knew better and thought that she was “beyond help.”

When asked if they had ever suspected her, Mr. Estes replied, “Would you be suspicious of your own mother? Why she was the most motherly lady my wife and I ever knew.”

His wife chimed in, stating that ‘Mrs. Gray’ was one of the most gracious hostesses as well.

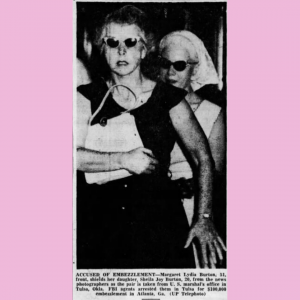

Mrs. Burton, despite being the subject of a national manhunt, boldly applied for a bookkeeper position at a local doctor’s office in Tulsa, Oklahoma under the name Madge Barton. Remarkably, Mrs. Burton and her daughter managed to integrate themselves into the community in a short period of time. Sheila Joy Burton, alias Joy Barton, enrolled at the local business college and was described by a teacher as a “quiet girl, refined in manner.” Mrs. Burton received the job and her employers, as usual, were impressed by her intelligence and acumen; however, Mrs. Juanita Hellwer, a receptionist, recognized Mrs. Burton based on a page one story that had run in the Tulsa World, a local newspaper. Mrs. Burton’s heavily freckled face, similar last name, and interest in bookkeeping aroused suspicions. These were confirmed when Mrs. Burton’s daughter came in to be treated and matched the description of “a buxom blonde.” Federal officers were tipped off, and Mrs. Burton and her daughter were arrested shortly after.

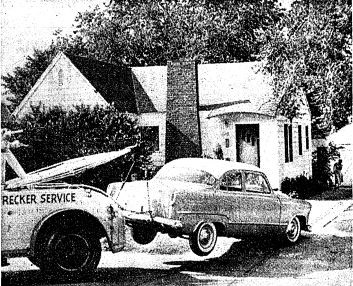

Government men tow off Mrs. Gray’s car from her rented home in Tulsa, Oklahoma to go towards repaying her debtors and former employers. The FBI agents also recovered three prize spaniels and a mink stole (Atlanta Constitution).

People in Atlanta had mixed emotions when Mrs. Burton was captured. Her former hairdresser, C. Charles, was glum, telling a reporter, “I surely thought she would give them a more exciting chase… And just what will the ladies in my saloon have to talk about now?” The doctors at the Decatur Clinic were unabashedly ecstatic: Dr. Robert P. Shinall told a reporter that “You can say this, we are happy!”

Margaret and her daughter, Sheila Joy Burton were driven back to Atlanta and were booked in the Fulton County Jail the next day to a media circus. Reportedly, her “friends on the second floor” fixed up the second floor for her arrival.

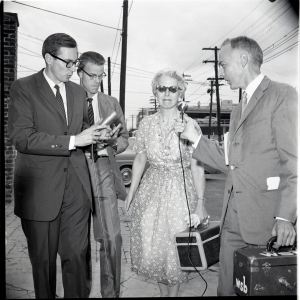

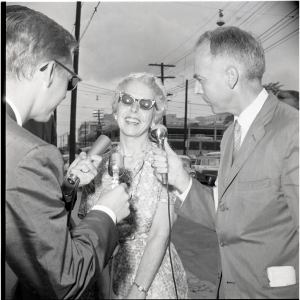

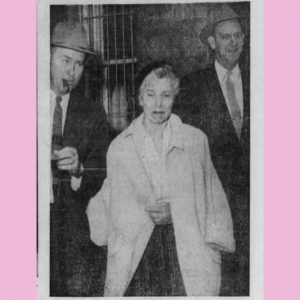

These series of photos were taken on August 29, 1957. Later that evening, Mrs. Gray responded to questions asked by reporters. Among those questions were about Sheila reuniting with her father, who lived in Athens, GA at the time and if Margaret would also reunite with her ex husband. It was reported Mrs. Gray appeared “tired” after traveling non stop from Tulsa. Guy Hayes Collection, DHC Archives.

Margaret and Sheila only had a short stay to “rest” before heading off to the DeKalb Jail to face trial.

All of Mrs. Burton’s many belongings, including her 1957 pink Lincoln were put up for public auction. The funds from the sale of Rise and Shine, the prize-winning dog, was valued over $5,000. The dog fetched an aristocratic price of $1,555 which was funded by cocker spaniel fanciers across the United States.

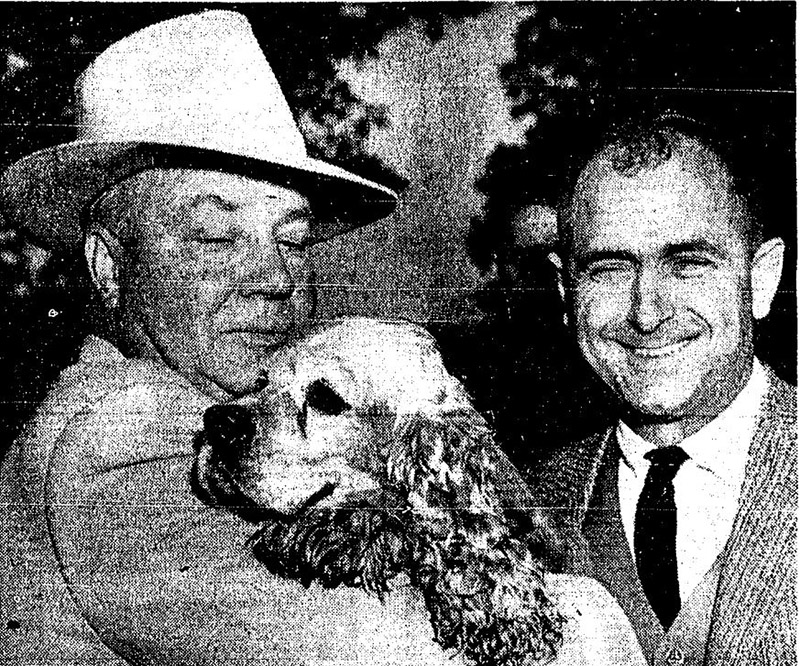

This image appeared in the Atlanta Constitution on October 27, 1957. Pictured are A.P Turnmyre and Joe Davis men who bid for “Shiney,” Mrs. Gray’s prize-winning cocker spaniel. The dog was sent to live with its breeder.

November 1957. Many of her items were advertised in the classified as “of Mrs. Gray”. Many other items of hers were advertised this way.

When Mrs. Burton took the stand, she sought to discredit her previous statement given to the FBI. She had previously admitted that she had stolen $50,000 when she was arrested in Tulsa, Oklahoma. She claimed that her confession was forced, she had only given the statement to free her daughter from jail. She explained to the jury that “If you [the jurors] had a daughter in custody, I believe that you would have done the same thing.” She continued, describing how the FBI showed her crying daughter to try and coerce her. Furthermore, she was not given access to a lawyer.

Mrs. Burton’s testimony denied that she stole from the Decatur Clinic. She claimed that the doctors had practiced income tax evasion. She had fled because she knew that the clinic’s accounts “were in a mess and she feared an income tax investigation.” She was in constant fear that the doctors would blame her; Mrs. Burton testified that “I knew that the doctors would throw it all in my lap.” She claimed that, had she committed the crime, she would have not turned over and worked to sort out the clinic’s accounting books.

Mrs. Burton described the clinic as a hectic place that did “tremendous” business.

Purportedly, doctors had a competition over which one of them could see the most patients in one day. Dr. Shinall confessed to her that “he could spend only 25 seconds with a patient and he’d never know he had been treated in so short a period of time.” Dr. Heard went so far as to keep a chart in his desk which graphed patients who were seen with business outcomes.

Some doctors were heavily criticized for not keeping pace.

The trial appeared to be difficult for Mrs. Burton. She was noted for her solemn mien “with a mouth slightly downturned, giv[ing] her a sort of weary, supercilious look.”After court adjourned, people would wait near the balustrade, clustering in groups, brushing past her and chattering with the latest speculation. Public interest meant that her every step was hounded: the Atlanta Journal noted that “not until she disappears… does the curtain go down for the day, and she has been the star all the way through.”

The shenanigans surrounding the trial were not limited to the courtroom. Rev. R Frank Crawley, a minister at the Decatur First Methodist Church, preached a Christmas sermon which sympathized with the doctors at the Decatur Clinic. He jested, “Instead of Mrs. Burton being on trial for taking money from four physician-employers, it appeared that the physicians might be on trial for making that much money.” While apparently, it got a good laugh from the congregation, the judge was not as pleased. A jury member, William Pitman, was attending Sunday service was there. The sermon was an opinion expressed to a juror. When asked how things looked (with the likelihood of a mistrial looming), the solicitor general cheekily quipped “Gray.” After a short recess, the judge ruled that the prejudicial comment could affect the presumption of innocence and thus declared a mistrial.

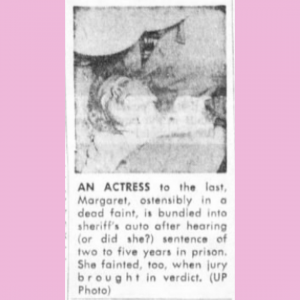

Due to this, Mrs. Burton was re-tried for a second time in February 1958. Her two trials caused Mrs. Burton immense stress, and it soon began to show. Towards the end of the trial, she experienced frequent fainting spells and suffered a fall at the DeKalb County jail.  On February 8, 1958, Mrs. Burton was indicted on two counts of larceny; the court ruled that she could serve two to five years per count concurrently at Reidsville State Prison.

On February 8, 1958, Mrs. Burton was indicted on two counts of larceny; the court ruled that she could serve two to five years per count concurrently at Reidsville State Prison.

On May 1958, the United States Federal Government brought deportation charges against her for “failure to keep the Government informed of her address and conviction of two crime involving moral turpitude and criminal misconduct.” Mrs. Burton could not be deported until she completed her prison sentence. Furthermore, she still had pending charges in California, Texas, Virginia and British Columbia.

So where did the two end up?

Sheila Joy, Mrs. Burton’s daughter, left Atlanta on September 2nd, 1957. According to local newspapers, her departure “ended a chapter in her life that would rival the wildest television drama.” She would stay with her uncle (on her mother’s side), Ian McGlashan, who was a movie producer. Charges against her as an accessory to her mother’s crimes were later dropped. Reportedly, she attended college and got excellent grades. When she was twenty-two, she married. It appears that after this period of excitement, she lived a largely ordinary life and had one child.

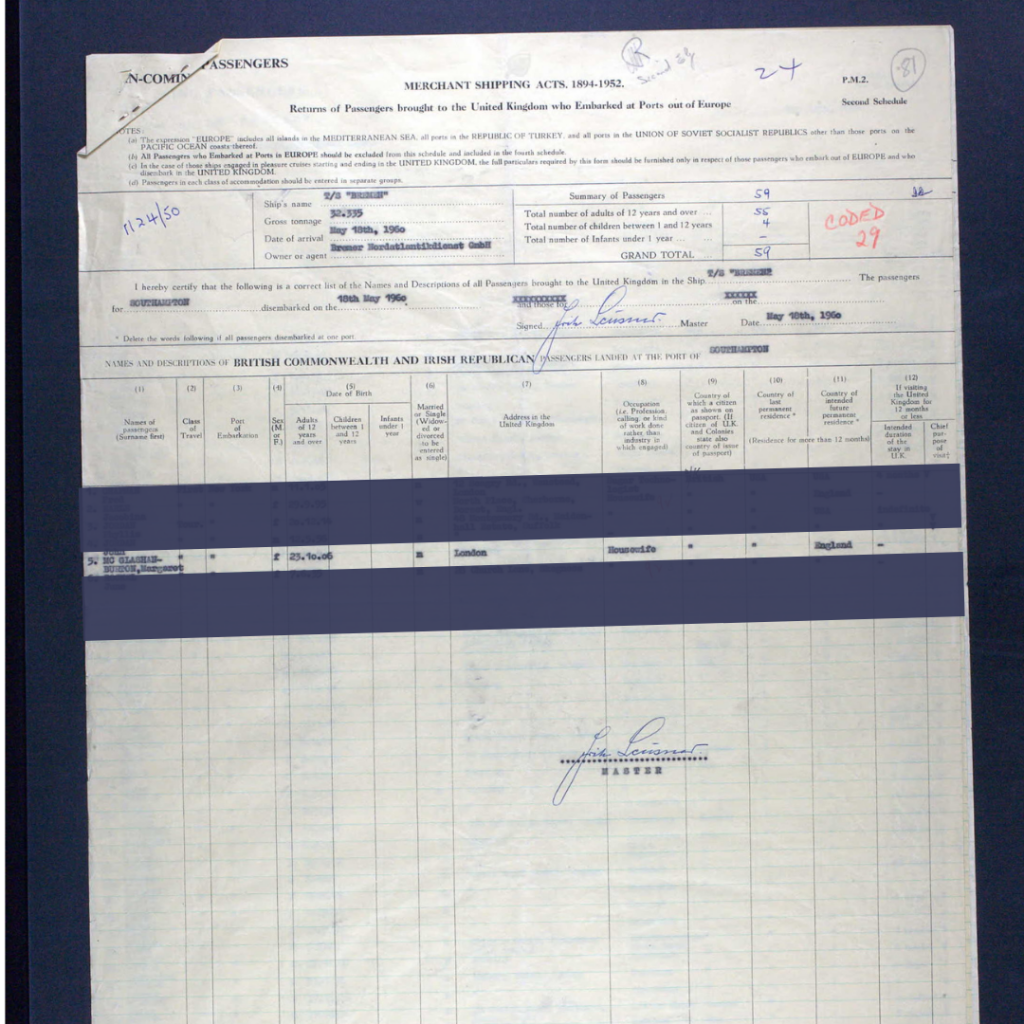

Mrs. Burton was released after serving eighteen months. Despite her attempts to fight it, she later was consensually extradited to California to face a charge of six counts of grand theft. She was sentenced in the California courtroom to 240 days in jail. On May 18 1960, she was deported to England.

She returned to California, where she died on October 2, 1992, in Los Angeles, California at the age of 85.

The case of Margaret Lydia Burton is undeniably compelling. This is the story of Mrs. Gray.

By Samantha Mooney, intern DeKalb History Center

Originally published May 2019.

Updated By Marissa Howard, January 2022.

References

Ashworth, Richard. “Mrs. Burton Goes from Prison to Jail.” The Atlanta Constitution, August 8, 1959. Accessed June 6, 2018. ProQuest. Byron, George Gordon Baron. 2001. Don Juan. Argentina: Longseller.

“China-born Divorcee Denies Stealing.” The South China Morning Post(Hong Kong), February 8, 1958. Accessed June 1, 2018. ProQuest.

The United States. United States Census Bureau. Census of Population and Housing. 2000.

The New York Times. 1958. “Clinic Aide Guilty of Larceny,” February 8, 1958. Accessed May 30, 2018. ProQuest.

“Doctors Fire Accountant Who Trapped Mrs. Burton.” The Atlanta Constitution, June 18, 1958. Accessed June 5, 2018. ProQuest.

“FBI Identifies Woman Sought in Fraud; ‘International Thief’ Likes Pastel Cars.” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 17, 1957. Accessed June 6, 2018. ProQuest.

“Freckles Are Downfall for Wanted Woman.” The Austin Statesman, August 22, 1957. Accessed June 1, 2018. ProQuest.

The South China Morning Post. 1958. “Hongkong-Born Woman Facing Deportation,” May 13, 1958. Accessed June 1, 2018. ProQuest.

“Mrs. Gray’s Dog Trainer Is Jailed in Connecticut.” The Atlanta Constitution, August 14, 1957. Accessed June 7, 2018. ProQuest. Johnson, Oscar. 1957.

“Mrs. Gray Put Cash in Satchel, Co-Ed Testifies.” The Atlanta Constitution, December 13, 1957. Accessed May 29, 2018. ProQuest.

Johnson, Oscar. “Decatur Semon Causes a Mistrial for Mrs. Gray.” The Atlanta Constitution, November 17, 1957. Accessed June 5, 2018. ProQuest.

Keasler, Jake. 1957. “Oh, How She Fooled Them.” St. Louis Dispatch, September 1, 1957, sec. The Everday Magazine. Accessed May 29, 2018. ProQuest.

McCartney, Keller. “Hunted Mrs. Gray Quits Caravan in N. Carolina.” The Atlanta Constitution, August 2, 1957. Accessed June 5, 2018. ProQuest.

McCartney, Keller. “Mrs. Gray Seized in Tulsa at Job in Doctors’ Office.” The Atlanta Constitution, August 22, 1957. Accessed June 6, 2018. ProQuest.

McLemore, Margaret. “Cocker Club Holds a ‘Wake’ to Swap Views on Mrs. Gray.” The Atlanta Constitution, August 22, 1957. Accessed June 6, 2018. ProQuest.

Moore, Charles. “Candy Slips Away to California.” The Atlanta Constitution, September 2, 1957. Accessed June 6, 2018. ProQuest.

“Mrs. Burton and Sheila to Face Georgia Trial.” The Austin Statesman, August 24, 1957. Accessed June 5, 2018. ProQuest.

“Mrs. Burton Gives in to Extradition.” The Atlanta Constitution, September 5, 1959. Accessed June 6, 2018. ProQuest.

“Mrs. Burton Is Given Deportation Hearing; U.S Referee Expected to Rule in Week.” The Atlanta Constitution, May 22, 1958, Constitution State News Service sec. Accessed June 4, 2018. ProQuest.

“Mrs. Gray Sits Alone As Yule Comes, Goes.” The Atlanta Constitution, December 26, 1957. Accessed June 1, 2018. ProQuest. Shannon, Margaret.

“Amid Trial’s Hue and Cry- Mrs. Burton Sites, Quietly.” The Atlanta Journal, December 15, 1957. Accessed June 6, 2018. ProQuest.

State of California. California Death Index, 1940-1997. Sacramento, CA, USA: State of California Department of Health Services, Center for Health Statistics. State of California.

California Marriage Index, 1960-1985. Microfiche. Center for Health Statistics, California Department of Health Services, Sacramento, California.

“Theft Trial Halted by Pulpit Comment.” The New York Times (New York City), December 17, 1957. Accessed June 4, 2018. ProQuest.

“Woman Fleeing Law Called Noted Thief.” Detroit Free Press, August 17, 1957. Accessed June 6, 2018. ProQuest.

“Woman on Trial in Clinic Theft.” The Arizona Republic (Phoenix), December 9, 1957. Accessed June 4, 2018. ProQuest.

“Woman on Trial Today on Embezzlement Count.” The Hartford Courant, December 9, 1957. Accessed June 5, 2018. ProQuest.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]